The Philippines has been slow to action and way behind its commitments to global initiatives on reducing or avoiding gas emissions harmful to the environment, despite the existence of many laws seeking to promote the use of renewable energy sources.

Instead of attracting investors in power projects run by non fossil fuels, the current regulatory environment has only discouraged foreign capital and even pushed big local players to put their money outside the country where the investment climate for renewable energy is considered “more hospitable.”

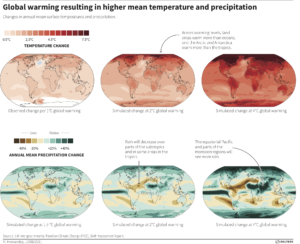

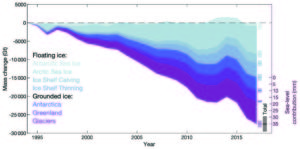

Globally, a lot is riding not only on turning to renewable forms of electricity generation, but also on moving away from fossil fuels such as coal and oil, and even natural gas, as the entire world has its sights on the 2050 goal of having greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduced to a net zero and limit global warming.

Against this backdrop, the Philippines appears to be gripped by inertia, especially when viewed along with the equally lofty goals of providing access to electricity for all and providing each household a choice of consuming electricity produced by renewable energy technology.

The International Energy Agency (IEA), based in France, notes that more and more countries are announcing pledges to achieve net-zero emissions—or balancing the amount of carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere with the amount of emission removed or avoided.

But the IEA says that even if fully achieved, these pledges so far put forward by governments fall well short of what is required to achieve net zero by 2050.

For the Philippines, the government in April 2021 committed to the United Nations Framework Conference on Climate Change to reduce and avoid 75 percent of GHG emissions for the period 2020-2030. This goal covers the sectors of energy, transport, industry, agriculture and wastes.

The big “but” is that only 2.71 percentage point of this goal is unconditional, which the Philippines can do on its own. The main part, or 72.29 percentage points, is conditional. This means that its policies and measures will have to conform with the Paris Agreement, the international treaty on climate change adopted in 2015.

Legal framework

Thus far, the Philippines’ toolbox that is helping these efforts include the Electric Power Industry Reform Act of 2001, the Biofuels Act of 2006, the Renewable Energy Act of 2008, the Climate Change Act of 2009, and the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Act.

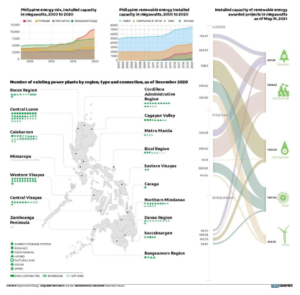

Last month, amid mounting criticism of failing to address a rising threat of power shortage, the Department of Energy (DOE) said that over the past five years, it had completed the mechanisms under the Renewable Energy Act to facilitate greater private sector investments in renewables. These include the traditional ones—hydro and geothermal—as well as solar photovoltaic, wind and biomass.

One facet of this that the DOE is drumming up is the participation of consumers by producing on their own the electricity that they need, or to choose renewable energy as the source of electricity delivered to their premises.

The mechanisms, the DOE said, include the Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) policy, Green Energy Option Program (GEOP) policy and Enhanced Net-Metering System. These three, among others, are geared toward achieving a 35-percent share of renewable energy in the country’s power generation mix by 2030.

The RPS is a market-based policy mechanism that requires power utilities to increase the use of renewable energy by 1 percent a year beginning in 2020 until 2030. The GEOP provides end-users the option to choose renewable energy facilities as their source of energy. Meanwhile, the net metering program enables ordinary electricity consumers to become a “prosumer,” with the ability to generate electricity for their own consumption and sell any excess generation to the distribution grid.

Wrong direction

According to Noel Estoperez, professor at Mindanao State University’s Iligan Institute of Technology, power generation using renewable energy started in the Philippines in 1913 with the 560-kilowatt Camp John Hay hydroelectric power plant that was developed by missionaries. As this flourished, hydro power was nationalized 23 years later through the law that also created National Power Corp. (Napocor).

Geothermal power came much later in 1979 in Tiwi, Albay. According to Guido Delgado, former president of Napocor, this facility that was initially rated at 55 megawatts and three years later at 330 MW, took 12 years to achieve commercial operations starting from a ceremonial lighting held in 1967.

After decades of incubation as a technology, solar and wind power started delivering to the Philippine grid in 2005. Biomass followed suit in 2009.

But in the Philippine Energy Plan 2018-2040, which was not finalized until November 2020, the energy department reiterates its stance of maintaining a “technology neutral approach” for an optimal energy mix.

This is explained as giving priority to “a reliable, sustainable and affordable energy mix” that will meet the country’s supply needs.

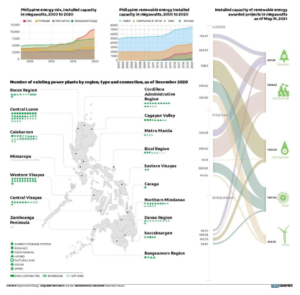

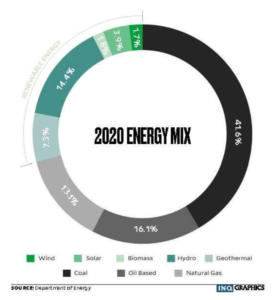

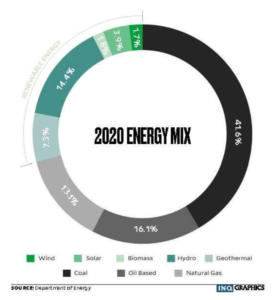

As of 2020, the share of renewable energy in the power mix was 29.2 percent, or 6,825 MW out of 23,410 MW of dependable generating capacity. The DOE defines dependable capacity as the capacity that “can be relied upon” or the performance that a power plant can actually deliver vis-à-vis its installed or nameplate capacity. This was a reduction from 32.5 percent in 2005 when solar and wind debuted in the mix and total dependable capacity across the archipelago was 13,595 MW.

Over the same 15-year period, the share of coal-fired power plants alone jumped to 43.8 percent (10,245 MW) from 25.2 percent (3,432 MW). Apparently, coal-based power may not be ecologically sustainable, but it is reliable and affordable.

Coal-based plants run round the clock as baseload facilities to cover the minimum demand while renewable energy facilities are dispatched mid-merit at best, to augment the baseload output when consumption kicks up. Also, power produced by coal-based energy arguably remains to be the lowest-cost for consumers.

Oil-based power plants—mainly used in small islands and also for additional capacity when demand peaks—accounted for 13 percent (3,054 MW) in 2020. In 2005, oil’s share was higher at 22.4 percent (3,403 MW).

Rounding up the fossil fuels that fire up generators is natural gas—also used for baseload plants—which represented 14 percent of total dependable capacity in 2020 (3,286 MW), going down from 19.9 percent (2,703 MW) in 2005.

In terms of actual output, renewable energy technologies accounted for 21.2 percent or 21,609 gigawatt-hours out of a total of 101,609 gWh in 2020. This was lower than the 32.4-percent share in 2005, when renewables generated 18,609 gWh out of a total of 56,568 gWh. That was the first year when renewables were part of the power generation mix, with a combined 19 gWh from solar and wind. Biomass power plants came online only in 2009.

Policy backlash

This technology-neutral policy is, in fact, a double-edge sword. On the one hand, neutrality means not promoting any technology such as renewables. The result is the end of subsidies for renewable energy platforms, particularly solar and wind power, at a time of healthy investor interest.

As recently as 2019, Energy Secretary Alfonso Cusi was reiterating that power-generation projects should be competitive rather than dependent on incentives such as the Energy Regulatory Commission-approved Feed-in Tariff rates and guaranteed dispatch—which are forms of government subsidy.

One result of this policy materialized in the form of big renewable energy facilities abroad that are backed by local companies, and foreign companies looking at other markets instead of the Philippines.

In April 2019, the Ayala group’s power generation platform AC Energy (Acen) marked the commercial operation of its first project in Vietnam. This was the $294-million, 330-MW Ninh Thuan solar farm, a joint venture with Vietnamese partner BIM Group.

Fernando Zobel de Ayala, president of Ayala Corp., who attended the ceremonial switch on, described the project as “a very large and meaningful investment” for Acen.

“Vietnam’s government has been very aggressive in attracting investments in renewables, particularly solar and wind,” Zobel said back then, noting that the Ninh Thuan facility was part of a renewable energy boom in Vietnam.

Eric Francia, president and chief executive of Acen, would be echoing this as recently as last month, when he said: “Vietnam is an ideal place for sustainable investments as it leads the race to clean energy transition in the post-COVID world.”

Over the next two years from the inauguration of the Ninh Thuan solar farm, Acen would announce renewable energy-related partnerships in India and Australia.

Other Philippine players such as the Aboitiz group are taking steps in the same direction. Aboitiz Power Corp., which had also explored Vietnam, is looking at opportunities in Indonesia.

More coal plants

The Philippines’ policy of neutrality in power generation technology, on the other hand, also means not discouraging any technology such as coal-fired plants. Advocacy groups like the Center for Energy, Ecology and Development call for a ban, despite the coal industry flexing “clean coal technology” innovations through high-efficiency, low-emission generators in tandem with “carbon capture storage and utilization.”

Also in 2019, Cusi told the committee on appropriations at the House of Representatives that a “moratorium on any technology is a disservice to our country.” On Oct. 27, 2020, the DOE chief would announce at an international forum that the government has decided on a moratorium on new coal projects.

The DOE would take almost three months, releasing in mid-January 2021 a written advisory that spelled out the policy. The umbrella group Power for People (P4P) Coalition finds this “underwhelming” considering that the ban was about no longer accepting new applications for endorsement of coal projects, instead of outrightly disallowing the construction of any new coal-fired facility.

According to P4P, there are at least 8,070 MW of coal-based generating capacity in the pipeline that will still be left untouched by the DOE’s “alleged effort to pursue a more sustainable power sector.”

In a 2018 report on its assessment of the Philippine energy sector, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) notes that compared to fossil fuel-based power generation, the permitting process for renewable energy development is more complex.

For one, the issuance of a Renewable Energy Service Contract must undergo a competitive selection process. Also, incentives for renewable energy such as duty-free importation and income tax reduction can be accessed only after the project has been issued the contract.

“The same regulations and permitting processes are applied to all renewable energy projects whether large or small scale, including renewable energy deployment in mini-grids to enhance energy access in areas that are not yet energized or that receive limited power supply,” the ADB said.

“The transaction cost and time for undergoing such lengthy regulatory processes can make smaller renewable energy projects unattractive to investors,” it adds.

Not enough

Still, the DOE has lists of “awarded” renewable projects, those that have been green lit and which include projects in predevelopment and ongoing development stages.

In terms of potential generating capacity, these projects total 11,284.92 MW of hydro; 814.2 MW of geothermal; 11,892.31 MW of solar; 5,760.58 MW of wind, and 182.03 MW of biomass. All in all, these represent 29,034.04 MW of additional capacity for the entire Philippines.

Assuming that all these projects are realized, they will cover almost a third of the additional 90,584 MW that the country needs in order to meet the projected peak electricity demand in 2040 under a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario.

But in a clean energy scenario (CES), the Philippines needs more additional installed capacity at 93,482 MW.

“The high requirement for additional capacity in the CES is attributed to having more renewables in the system, specifically solar and wind that are considered variable capacity,” the PEP 2020-2040 explains.

This downplays a generator’s capacity as described by the manufacturers—thus called “installed capacity” or “nameplate capacity.” It is more practical to look at the dependable capacity, much more so with solar and wind, considering that these are intermittent and dependent respectively on the intensity of sunlight and the movement of air.

Also, the PEP 2020-2040 clarifies that the CES does not mean all-renewable. In fact, the scenario takes into account capacity contribution from natural gas—crude oil’s twin and coal’s less-polluting cousin—and “other low-carbon and highly efficient technologies.” This latter part suggests that coal remains in play.

Further, the two-decade plan tags the investment cost of the needed additional capacity under the BAU scenario at $104.7 billion. The cost of additional build needed for the CES is $124 billion, higher by 18 percent.

And this is partly why industry players balk at the idea of a swift and wholesale shift to clean energy, despite civil society’s assertion that the technologies and natural resources are readily available to make the transition.

Expensive technology

“I think, at the end of the day, there must be a commercial basis as to the choice between coal and [natural] gas for example or even renewables, and at the same time we are mindful of the power rates that we will charge to the consumers,” Manila Electric Co. (Meralco) chair Manuel V. Pangilinan says at a press briefing held last July.

Not only is Meralco the biggest electricity distributor in the Philippines, it is also building up a considerable presence in power generation.

“It’s alright to talk about renewables and gas, but if it translates into higher prices, that obviously will be met with some resistance, particularly politically,” Pangilinan points out.

Additionally, Pangilinan argues that the shift to renewables is a difficult choice, especially if the question of “who will pay for the cost of migration” is left unclear.

“I wish it were [an easy choice], but renewables don’t provide the kind of capacity that will supply the reserves that we need moving forward,” he adds. “I don’t think it’s a clear-cut case for renewables.”

In other words, the question is about balancing the cost against the pace of the energy shift. Currently, coal and gas cover Meralco’s baseload supply needs while renewables are primed to exclusively provide the company’s mid-merit requirements—which represent 29 percent of contracted capacity.

Meralco has also made a commitment to invest in and develop at least 1,500 MW of renewable energy projects over the next five to seven years.

Ray Espinosa, president of Meralco, points out that considering the prevailing sentiment to move away from coal, the burden of providing baseload supply falls on natural gas —now considered as the “transition fuel,” since it is cleaner than coal albeit still formed from fossils and thus rich in carbon.

Coal-free target

Indeed, other players like the Ayala group have set a goal of having their power-generation business coal-free by 2030. In 2019, AC Energy and Infrastructure Corp. completed the divestment of its 60-percent interest in the 632-MW GNPower Mariveles coal-fired plant in Bataan. This was sold to its partner, the Aboitiz group.

Ayala is in the process of offloading its 85-percent interest in the 552-MW GNPower Kauswagan coal-fired plant in Lanao del Norte; the remaining 35-percent stake in the 244-MW coal-fired plant of South Luzon Thermal Energy Corp. in Batangas, and the 40-percent stake in the 1,336-MW coal-fired plant of GNPower Dinginin in Bataan.

The Aboitiz group itself has announced a P190-billion investment program to achieve a 50-50 balance in its renewables business and its conventional thermal generator assets.

“If decarbonizing the system is the goal, Meralco cannot do it alone without working with the rest of the power industry and of course with the government,” Pangilinan said. “Government has got to participate in that transition, which will be painful if done in a short timeframe.”

Alas, P4P, the consumer welfare coalition, laments the continued nonmention of the energy sector in President Duterte’s latest and final State-of the Nation Address last month.

Achievable goal

According to the IEA, global carbon dioxide emissions are expected to reach new record levels starting 2023 amid government spending shortfalls in the transition to clean energy, especially in emerging and developing economies.

“Since the COVID-19 crisis erupted, many governments may have talked about the importance of building back better for a cleaner future, but many of them are yet to put their money where their mouth is,” Fatih Birol, executive director of IEA, said in a statement.

“Despite increased climate ambitions, the amount of economic recovery funds being spent on clean energy is just a small sliver of the total,” Birol said.

Based on an analysis of 800 national policies including several that are implemented by the Philippine government, the agency found that governments have mobilized $16 trillion in fiscal support throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. However, only 2 percent or about $320 billion of the total is earmarked for clean energy transitions.

“Not only is clean energy investment still far from what’s needed to put the world on a path to reaching net-zero emissions by mid-century, it’s not even enough to prevent global emissions from surging to a new record,” Birol said.

Birol said the path to net-zero emission by 2050 “is narrow but still achievable,” but governments must act now by leading clean energy investment and deployment “to much greater heights beyond the [pandemic] recovery period.

This story, originally published by the Philippine Daily Inquirer, has been shared as part of World News Day 2021, a global campaign to highlight the critical role of fact-based journalism in providing trustworthy news and information in service of humanity. #JournalismMatters.