China’s President Xi Jinping pulled a surprise at the United Nations in September when he committed the world’s biggest energy user and greenhouse gases emitter to a “carbon neutral” goal by 2060, becoming only the second major economy to do so.

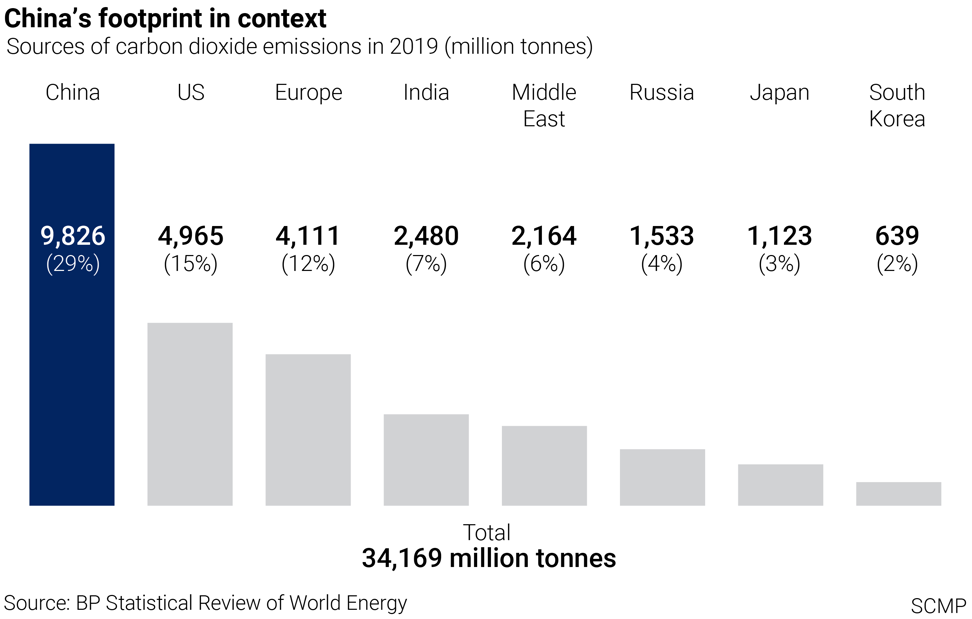

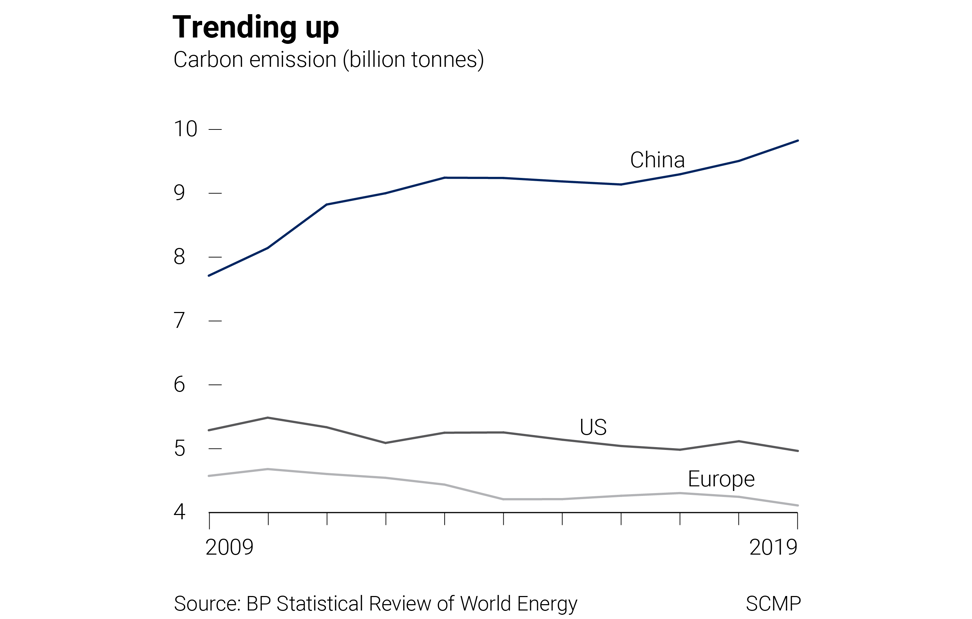

China emits more carbon dioxide, a by-product of fossil fuels and industries, than the United States and Europe combined, at a rate that tripled in the past two decades amid the country’s breakneck economic growth as a World Trade Organization member. The 2060 goal, along with a target for carbon emissions to peak before 2030, is critical to put the world on track to meet the 2016 Paris Agreement of capping global warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100.

To reach Xi’s target, China must wean the planet’s second-largest economy – which burns half of the world’s coal, and imports more oil and natural gas than anywhere else – off fossil fuels. It’s an ambition that may cost US$5.5 trillion over the next few decades as carbon is removed or offset in energy production, heavy industry, buildings, transport and agriculture, involving technology barely used today, according to Sanford C. Bernstein’s estimate.

“Although this is a 40-year [goal], the target is so ambitious that we will have to start immediately,” said Thomas Palme, who leads Boston Consulting Group’s social impact practice in China. “China is already doing a lot, but it needs a step-change to get on the path of what President Xi has announced.”

The next key step would be for China to launch a long-awaited national carbon emissions quota trading scheme, a cornerstone policy that can turn Xi’s pledge into a deliverable reality. It is one of the most effective tools, besides green financing products, that uses market forces to put a price, or financial penalty, on carbon emission. A carbon futures exchange is due for commencement this year in Guangzhou, augmenting the brisk transactions of emission certificates that had been ongoing in the Guangdong provincial capital since 2013.

ETS directs polluters to find the most cost-efficient way to cut emissions. China’s national ETS will initially cover coal and gas-fired electricity generators, before expanding to seven pollution-prone industries: petrochemical, chemical, construction materials, steel, non-ferrous metals, paper and domestic aviation.

Nearly 1,700 of these carbon emitters, each with at least 26,000 tonnes of annual carbon dioxide emissions, will initially be allocated free quotas based on their historical volumes. Companies that need to surpass their emission quota must buy additional permits to discharge, and such payments can be used to finance government initiatives in emission abatement.

China’s annual growth rate in carbon dioxide emission has already flattened since 2013 at less than 2 per cent, down from the 8.2 per cent average in the previous 10 years, according to the Our World in Data website in the UK. Still, the Chinese ETS is likely to cap an estimated 3.3 billion tonnes of annual carbon dioxide emissions as soon as it is launched, 80 per cent more than the 15-year-old peer by the European Union, the world’s oldest and largest such system.

Yet, Beijing has not given a launch date, raising concern that the ETS’ 2020 launch date – set three years ago – may be delayed again due to the coronavirus pandemic and its debilitating effect on the global economy.

“The 14th five-year plan (2021-25) will be a landmark period for the establishment of China’s nationwide carbon market, with regional pilots transitioning to a unified national market, single-industry participation expanding to multiple sectors,” said Li Gao, head of the climate change department at the Ministry of Ecology and Environment.

China’s national ETS incorporates lessons learned from pilot schemes set up in 2013 in Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing, Shenzhen, Guangdong and Hubei.

Together, the pilots involved close to 3,000 enterprises from over 20 industries trading more than 400 million tonnes of carbon emission permits valued at 9 billion yuan (US$1.36 billion).

Data accuracy is vital in an effective carbon market because the financial penalty for emission has to be high enough to drive abatement.

“Collecting and aggregating the right data accurately is not simple because different facilities may have different carbon intensities, depending on where you buy the coal and its energy content for example,” said Chan Wai-Shin, HSBC’s global co-head of environmental, social and governance research.

The data accuracy challenge is not unique to China. South Korea gave companies five years to set up a data collection system before rolling out carbon trading.

Another linchpin for the ETS is the methodology for allocating emissions quotas. On this score, the Chinese government has given few details, with the consultation circular on the provisional trading rules saying it would take into account the national emission goals, economic growth and industry structure adjustments.

The ETS may gradually transition from allowances based on a polluter’s production level to one with an absolute cap, said Ma Jun, director of the non-profit Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs in Beijing.

“The cap should be clear for each plant’s emissions, so that we can effectively promote carbon trading and cut emissions,” Ma said.

The impending transitioning of trading currently imposed on certain firms – and done on a regional basis via pilot exchanges – to the new industry-wide national trading platform will be a policy challenge.

“Participating companies in cities with pilot ETS programmes are facing an increasingly higher bar for free emission quotas and limited room for further reduction, while non-participating players may have advantages as later comers,” said a spokesperson at the Shanghai office of German chemical firm Covestro which faces the transition.

The world needs to price carbon at more than US$40 a tonne to reach the tipping point for greenhouse gas abatement to pick up pace, said Richard Mattison, CEO of Trucost, the environmental risk analysis unit of S&P Global. That bar would rise to between US$50 and US$100 per tonne next decade, 13 leading economists supported by the World Bank said in a 2017 study.

For now, carbon emissions are changing hands at below the consensus price, with the ETS permits trading at €27 (US$32) per tonne, while prices among China’s seven pilot schemes ranged between US$1.4 and US$11 per tonne, according to the inter-governmental initiative International Carbon Action Partnership.

“There is a very big gap between the price that carbon emissions are currently traded at, and the effective carbon price needed to drive emissions reduction in line with the commitments under the Paris Agreement,” Mattison said.

Initial emission quotas need to be aggressively handed out to achieve the tipping point, he said, adding that Europe’s allocation equivalent to 90 per cent or more of companies’ emission volumes had resulted in modest reductions over 15 years.

“The EU aims to halve its carbon emissions in four decades by 2030, while China has pledged to cut it to near zero in the next four decades,” he said.

If investors, speculators and traders are allowed to trade futures and derivative products, they can play a role in setting carbon price and boosting trading volume, said Zhang Jianyu, chief representative of the China programme of New York-based environmental non-government organisation Environmental Defense Fund, which advises China on the launch of its national carbon market.

“The Chinese government intends to use futures to promote investment and financing to indirectly facilitate efforts to reduce carbon emission,” said Cai Yongmei, a partner of international law firm Simmons & Simmons who advises on derivatives and structured products deals.

Green bonds, green loans and carbon tax could also play a big part in financing low carbon energy and manufacturing technologies and infrastructure.

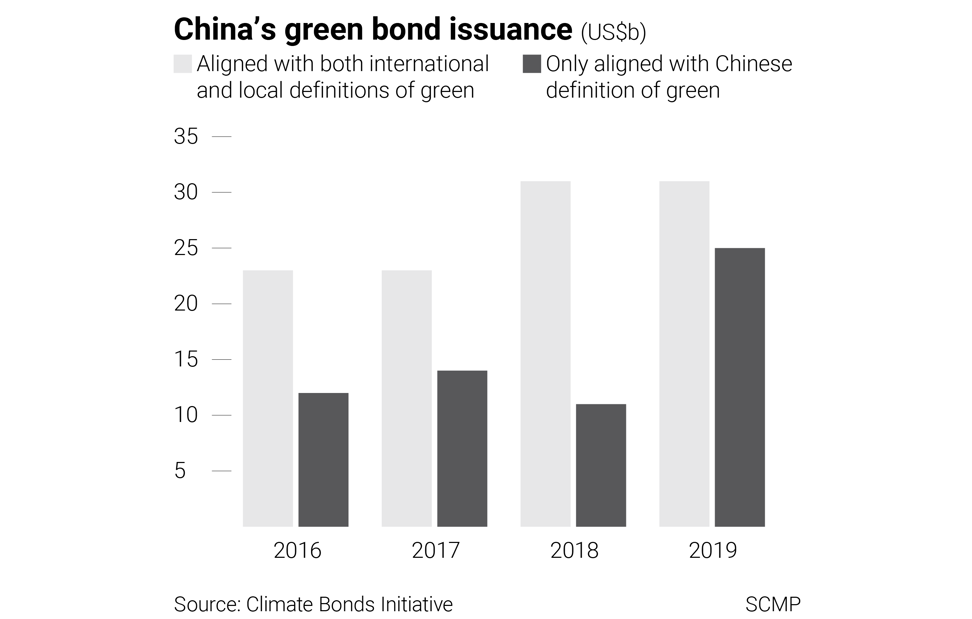

China was the world’s biggest green bonds issuer last year, printing 386 billion yuan of papers, a third higher than in 2018, although only around half met international standards, according to London-based non-profit Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI).

To narrow the gap, the People’s Bank of China this year revised issuance guidelines to remove “clean utilisation of fossil fuels” from the list of projects that can qualify as “green,” but the central bank still allows up to half of the proceeds to be used as “general working capital” not earmarked for specific green projects, well above 5 per cent of the CBI’s standards.

Chinese guidelines are expected to converge with global standards in the long term, which will open up domestic green bonds to foreign investors, said Fitch Ratings. Some foreign firms issued green bonds linking interest payments to attainment of sustainability targets, which could have showed a different way for Chinese utility-sector green paper issuers to improve sustainability achievement, said Andy Chang, fixed income credit analyst at JP Morgan Asset Management.

Hong Kong is well placed to seize the opportunity to act as a bridge between international investors and mainland Chinese firms seeking to raise funds for low carbon projects, said Christopher Hui Ching-yu, Secretary for Financial Services and the Treasury.

“Hong Kong, as a comprehensive international financial centre and a global yuan business hub, is well-equipped to develop into a leading regional hub for green and sustainable finance,” he said in written comments to South China Morning Post.

The city’s rules on environment, social and governance matters for listed firms would also put it in good stead as a green finance hub, said Deloitte China’s risk advisory director Herbert Yung.

Although Hong Kong has yet to set a long-term goal to cap carbon emission, when it does, there will be demand for quotas trading.

Due to the small size of the local market and a lack of carbon trading infrastructure, it should consider joining forces with neighbouring mainland cities to create a common market, said Ma Jun, chairman of Hong Kong Green Finance Association.

The city’s Environment Bureau is working with stakeholders in “setting the direction” for carbon neutrality by 2050, Joseph Chan Ho-lim, Under Secretary for Financial Services and the Treasury told a green finance forum hosted by the association this month.

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to curb global economic activities and carbon emission, the urgency to deploy market-based tools to bolster efforts to fight climate change has not changed, according to HSBC’s Chan.

“Globally, carbon emissions are expected to fall 4 to 7 per cent this year amid the pandemic,” he said. “However, what matters for climate change is the cumulative emissions in the atmosphere … this pandemic may just be a blip in atmospheric concentrations of emissions and will not change the tools used to transition towards a low carbon economy.”

This story, originally published by South China Morning Post, has been shared as part of World News Day 2021, a global campaign to highlight the critical role of fact-based journalism in providing trustworthy news and information in service of humanity. #JournalismMatters.