CLIMATE anxiety is real – and it’s going to get far worse according to the latest report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a body of scientists backed by the United Nations.

The report, approved by 195 governments in a virtual meeting early this month and based on more than 14,000 studies, confirms that the world is surely and irrevocably warming – even though some politicians and industrialists may still deny it.

More alarming is that, as the IPCC report points out, even if governments were to drastically and immediately cut carbon emissions today, we can no longer stop global warming from intensifying over the next 30 years.

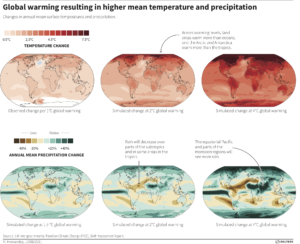

Total global warming, says the report, is likely to rise by around 1.5°C within the next two decades and along with that hotter future comes its attendant effects.

This means that heatwaves, such as the one that slammed into the Pacific North-West of Canada and the United States and sent temperatures into the high 40s a few months ago, as well as wildfires in Europe, Nordic countries and Siberia, and deluges in Germany and China will become more frequent.

The most damning aspect of the IPCC report, however, is that humans are the only ones to be blamed for this hot mess we’re in, with the rise in global average temperatures being driven by countries burning fossil fuels, clearing forests and spewing greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane into the air.

If that isn’t enough, a paper recently published in the Nature Climate Change journal suggests that a crucial ocean circulation system in the Atlantic called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC), which helps to stabilise the climate in Europe, is showing signs of slowing down.

Although it is yet to be established if this is linked to climate change, the slowing, if proven true, further imperils the state of our planet.

In the words of the United Nations secretary-general António Guterres, this is nothing less than a “code red for humanity”.

Apocalypse now?

While Malaysia seems to have escaped for now much of the heat-induced stress – the south-west monsoon is even wetter this year so we are not expecting to see haze from Indonesia – global warming will affect Malaysia.

This is because much of the weather in Malaysia, particularly Peninsular Malaysia, is influenced by the monsoon system.

Universiti Malaya climate expert Prof Datuk Dr Azizan Abu Samah says Malaysia is on a maritime continent, an important component of the whole global circulation heat engine.

“We are also influenced by what happens – not only in the Northern Hemisphere, especially during the north-east Monsoon, but also by the Southern Hemisphere related to the south-west monsoon.

“So any warming or cooling in the mid-latitudes, especially during the Northern Hemisphere or Southern Hemisphere’s winter, will have an impact in weakening or strengthening our monsoons,” he says in an interview last week.

Should this happen, it will have an effect on the biological productivity of the Bay of Bengal and South China Sea, which are very much influenced by the monsoon.

Normally, a tropical ocean is less productive biologically compared with the colder oceans in the midlatitudes and polar regions – except for the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea.

“This (effect on the monsoon) will have a grave consequence for the fisheries and the region’s food security,” explains Prof Azizan, pointing out that the marine ecosystem in these areas is already under stress from overfishing.

“Global warming will further stress these seas and the ecosystems,” he adds.

Prof Azizan, who is from UM’s Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences, says being in the humid tropics, he does not anticipate prolonged drought in Malaysia, such as that experienced by northern Australia that is associated with the El Niño-Southern Oscillation or Enso.

“We may have a few weeks without rain around February which is our normal drier period. This will be further enhanced if Enso is also present,” he says.

However, Prof Azizan points out that in a warmer world, the atmosphere will be able to store more water vapour, usually translating to stronger thunderstorms and more rainfall.

“Depending on the duration of the rain, this can result in frequent flash floods or, if the duration is longer, river flooding (akin to) the 2014 flood,” he says.

The 2014 flood, which affected over 200,000 people and killed 21, devastated parts of Kelantan, Terengganu and Pahang on the East Coast, as well as other states.

It also damaged infrastructure, including homes, highways and rail lines, to the tune of billions of ringgit.

The stronger monsoon in the region is the north-east monsoon, which lasts from November to February and is also the time of heavy rain for Peninsular Malaysia.

Most weather models, says Prof Azizan, are predicting a weaker north-east monsoon and a stronger south-west monsoon from global warming.

“That is why regionally, they are predicting that Indonesia south of the equator will experience a drier climate in the future due to a weakened north-east monsoon,” he says.

Melting pot

While the present IPCC report approximates a sea rise level of about 3.2mm per year from glaciers melting in Greenland and the Antarctic continent, many glaciologists, says Prof Azizan, feel this to be an underestimation.

He says there are two components to rising sea level, one which is about 50% due to water expansion as ocean temperatures rise, and the other is from glacier melting.

“However, many Antarctic glaciologists think that this (the IPCC forecast) is an underestimate due to the rapid melting of the West Antarctic ice shelf that is now unstable.

“This may contribute a further 7m of sea level rise if all of the West Antarctic ice shelf were to melt away,” he says.

Also being threatened are the mangroves, seagrass and coral species along Malaysia’s coastlines – already these are under stress from development and, before the days of Covid-19, overtourism.

Such damage basically leaves the country’s coasts “naked” and vulnerable to floods and erosion.

Pointing out that Malaysia is a “mega biodiversity region”, Prof Azizan says this area hosts about 70% of the world’s mangrove, coral and seagrass species.

“So our ocean is an important biodiversity refugia that is under threat from global ocean warming and acidification.

“While we tend to focus on conserving our terrestrial biodiversity like our rainforests, it is our ocean that plays an important refugia for global ocean biodiversity.”

(Refugia refers to an area in which organisms can survive unfavourable conditions, especially glaciation.)

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia’s climatologist Prof Dr Fredolin Tangang, who authored a number of scientific papers cited in the IPCC report, says it does not specifically provide information on the future climate of a particular country.

However, he says that “Malaysia is projected to experience increased extreme climate events in future: “These include more heatwaves, more droughts and floods as well as rising sea levels in decades to come if there is no deep cut to greenhouse gas emissions soon,” he says.

Prof Fredolin is the review editor for Chapter 10 of the IPCC report as well as a contributing author of the Atlas Chapter.

Lest any climate sceptic tries to throw doubt on the report, Prof Fredolin says it represents a credible body of scientific evidence on the climate system that is based on a comprehensive and holistic, open, robust and transparent assessment of related published literature, involving over 1,000 authors and editors.

Although the Nature Climate Change paper was not assessed in the IPCC report having been published recently, Prof Fredolin believes that the collapse of the MOC will likely trigger an abrupt change in regional weather, including Malaysia’s, which is regulated by the monsoon cycle.

“I believe there is no particular paper addressing how this affects climate in Malaysia but this would be an interesting issue to investigate,” he says.

However, Prof Azizan believes that changes in the Atlantic will have only an indirect impact on Malaysia.

“The more direct impact will be changes in the Pacific and also the Indian oceans.”

No more talking shop

With slightly more than two months to go before the Glasgow Climate Change Conference at the end of October, the IPCC report has upped public expectation for the thousands of negotiators, politicians and diplomats to at last come to an understanding.

However, despite the fact that humanity’s survival depends on it and despite high hopes and criticisms, each time the conference has a dismal record of not performing up to expectations.

Should an effective agreement fail to materialise from Glasgow, current policies being pursued by governments will likely push warming up by 3°C by the end of the century, warns the IPCC report. In contrast, the goal of the much hailed Paris Agreement of 2015 has been to limit global warming to well below 2°C or preferably 1.5°C compared with preindustrial levels.

“The current pledges under the Paris Agreement won’t be able to cap the warming under 1.5°C and 2°C. More impact from extreme climate is expected in future decades,” agrees Prof Fredolin.

The report, he adds, also indicated that without deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C threshold is projected to be breached between 2021 and 2040 – likely in 2030 – and 2°C in 2050.

However, scientists behind the IPCC report believe there is still a chance to avoid the more harrowing effects of global warming by preventing the planet from getting even hotter.

According to the report, if a coordinated effort among countries can head off CO2 emissions by 2050 by moving away from fossil fuels and removing carbon from the atmosphere, this will allow global warming to likely halt at the level of around 1.5°C.

Failure is not an option because as many of the young climate strikers like to remind us – there is no Planet B.

Eye on the future

Malaysia’s main priority now, according to Prof Azizan, is to plan a more climate-resilient, sustainable socioeconomic strategy.

“This is to anticipate a soft landing for our nation and region in the future as the world warms up,” he says.

He argues that even if Malaysia is not a major emitter of greenhouse gas, the existing greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere have already locked in a future global warming of 1°C to 2°C.

“So the question is more about how much warming is acceptable to maintain our status quo without any major climate shift and to maintain the ecosystem that we are familiar with or adapted to,” he says.

The 10 biggest emitters of greenhouse gases (in descending order) are China, the United States, the European Union, India, Russia, Japan, Brazil, Indonesia, Iran and Canada.

Prof Fredolin says given the fact that Malaysia’s emissions contribute less than 1% to total global emissions, the focus should be on adaptation measures in increasing climate resilience.

“Having said this, of course, the country should enhance mitigation measures consistent with what is required by the Paris Agreement.”

Both Prof Fredolin and Prof Azizan agree on one thing: the country has to quickly come up with a national adaptation plan or strategy.

While Environment and Water Ministry secretary-general Datuk Seri Zaini Ujang told The Star in April that the government is coming up with specific legislation and policies to tackle climate change, there is currently no national adaptation plan.

“We need to look into water and food security strategies, using the climate scenarios of a warmer world,” says Prof Azizan, suggesting that Malaysia uses the Enso as a natural scenario to study how the ecosystem responds and from this, plan how coastal, rural and urban areas can adapt to changes.

Malaysia, he points out, needs to plan up to 30 years into the future.

“This is so that we can slowly build the necessary investment and governance structure at the macro level based on a number of scenarios – from optimal to a worst case scenario – and test how our ecosystem and socioeconomic system adapt.

“The bottom line is the world is getting warmer and we have no choice but to plan for it so that we can avoid a climate crisis in the future.”

This story, originally published by the The Star, has been shared as part of World News Day 2021, a global campaign to highlight the critical role of fact-based journalism in providing trustworthy news and information in service of humanity. #JournalismMatters.