The Shenzhen-based company rolled out a fleet of 600 lorries in June 2019, each fitted with a hydrogen fuel cell engine, capable of travelling as far as 350 kilometres (217 miles) before refuelling. The vehicles, comprising light delivery trucks and 4-ton lorries, were leased to couriers, logistic companies and garbage collectors.

“It is a near certainty that the government will allocate a huge sum of additional funds to subsidise of hydrogen-powered vehicles,” the company’s vice-president Li Junzuo said in an interview with South China Morning Post in Shanghai. “An increased financial support will facilitate our expansions.”

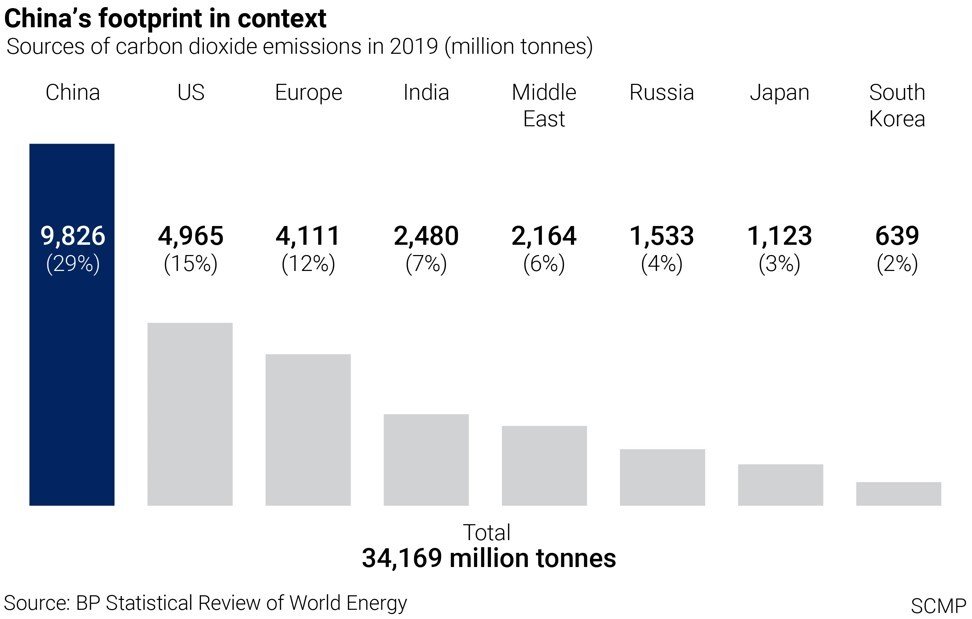

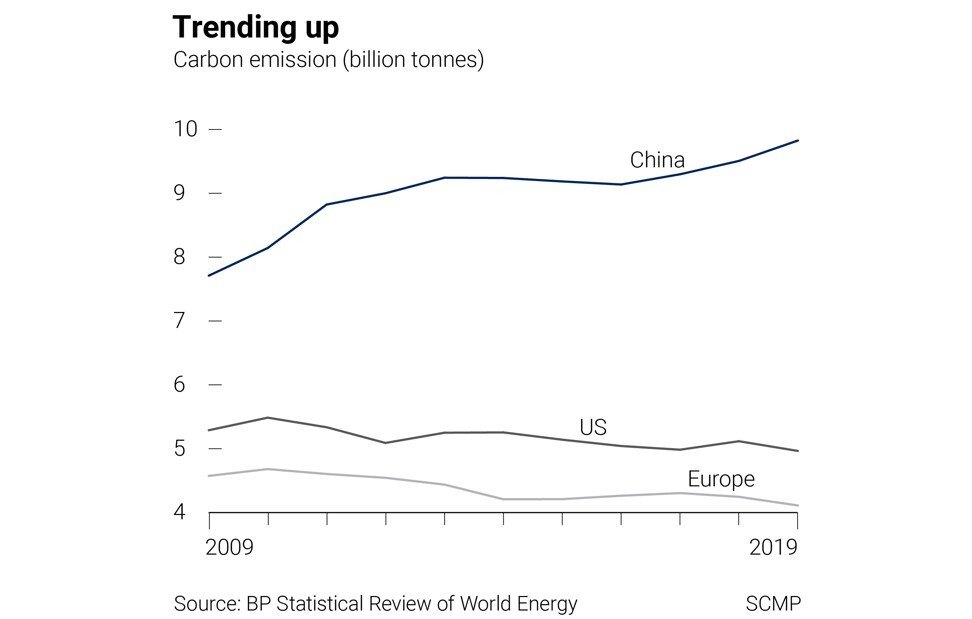

A little more than a year later, China’s President Xi Jinping pulled a surprise at the United Nations, setting a 2060 target for the country to attain carbon neutrality, becoming the second major economy in the world to put a date on the ambition.

As the world searches for the fine print of Xi’s plan – the implementation details are to be outlined in the country’s next five-year plan in March 2021 – Qingliqingwei is doing a roaring business. Its story underscores how far the Chinese government has put its considerable financial resources behind projects with very long-term, and often uncertain commercial viability.

China offers up to 400,000 yuan (US$60,836) in subsidies per fuel-cell vehicle (FCV) once it runs at least 20,000 kilometres. Fleet operators like Qingliqingwei – a pun on “do it yourself”” that replaces the “self” with hydrogen – get 30 per cent of the subsidies.

For a monthly fee of about 5,000 yuan, the trucks are leased mostly to couriers, deliverers and retailers like JD.com and Alibaba Group Holding‘s Cainiao logistics unit. JD.com, one of China’s largest online retail platforms, operates 150 FCVs around Shanghai. The trucks, bought for 830,000 yuan each, comes from local manufacturers like Nissan Motor’s Chinese partner Dongfeng Motor, each fitted with a fuel cell engine.

“We serve as a bridge between the upstream vehicle manufacturers and downstream clients using trucks for logistics use,” Li said, adding that Qingliqingwei plans to expand its fleet to 3,500 trucks. “The government policies play a decisive role in the promotion of hydrogen-powered vehicles. Without cash subsidies, none of us can survive the lofty costs on purchases and running.”

Fuel cells produce power through an electrochemical reaction of hydrogen with oxygen, generating heat and water as the by-products. They are a cleaner alternative to internal combustion engines (ICEs) that burn petrol and spew carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and other noxious gases. They are also considered more environmentally friendly than electric vehicles that run on lithium-ion batteries, which are hard to dispose of.

The first hydrogen fuel cell was created in 1839 by British lawyer and physicist William Grove, by splitting water into different cells containing hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen was also used in the 1960s by the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa) to supply power during space flights, since it did not emit heat or pollution into sealed spacecraft.

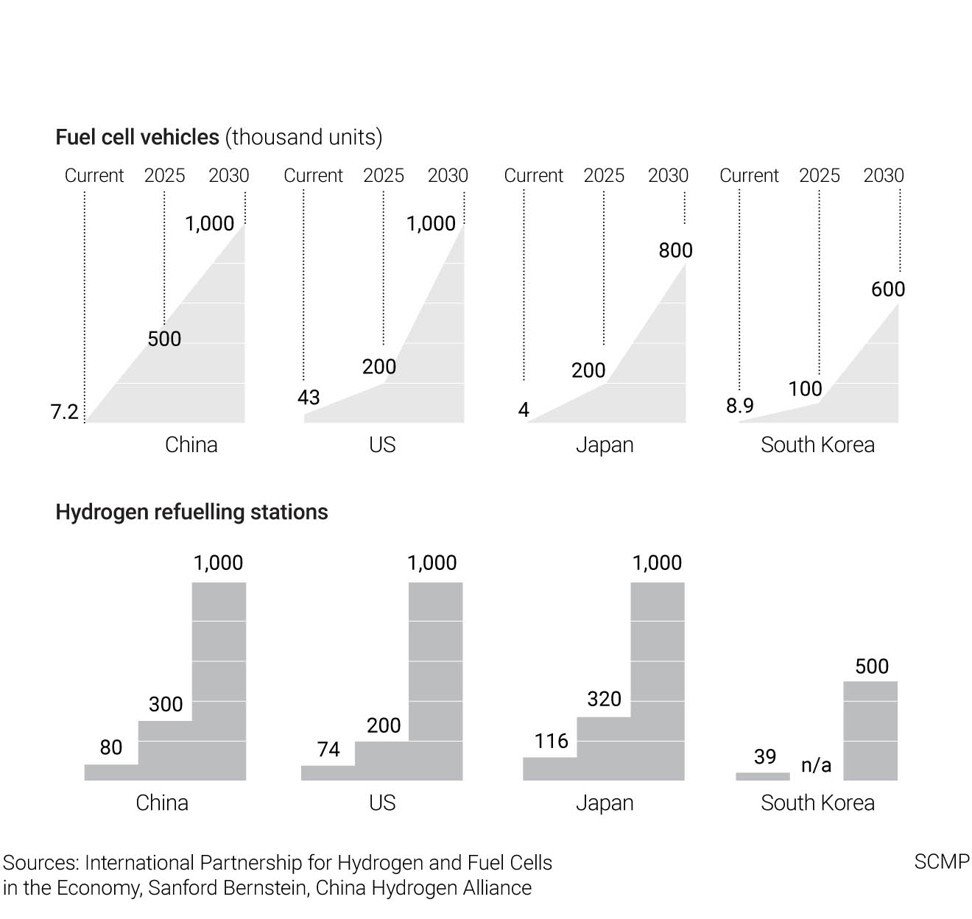

Global assemblers of passenger vehicles, sports-utility vehicles, sports cars and luxury sedans have been slow to embrace hydrogen fuel cells, mostly over concern of their limited driving range, and the shortage of hydrogen refuelling stations. Almost all of the 7,200 fuel cell vehicles on China’s roads in July were retrofitted commercial trucks.

That may be about to change, as the European Union, Japan and South Korea – each with a robust car assembling industry – are also looking to hydrogen to help their commitment to carbon neutrality by mid-century.

Toyota Motor, the world’s second-largest carmaker by volume, was the first to launch a commercially viable FCV with its Mirai midsize sedan, first unveiled at the 2014 Los Angeles Auto Show. The 2016 model Mirai could go as far as 502 Km on a full tank, comparable to an electric vehicle. As of December, Toyota sold 10,250 Mirais, 60 per cent of them in the US, and a third of them in Japan.

In September,

“After several false starts, the hydrogen economy has reached prime time,” according to a Sanford Bernstein report. “While hydrogen is not yet cost competitive with other energy sources, the anticipated over 50 per cent reduction in hydrogen production cost to less than US$2 a kg and 80 per cent reduction in fuel cell costs [in the next 30 years] will be a game changer.”

Fuel cells could make up 10 per cent of China’s energy consumption by 2050, according to the projection by the China Hydrogen Alliance, an industry guild. Bernstein puts it at 11 per cent. To reach that goal, China is aiming to have 1 million fuel cell vehicles on the roads by 2030, served by 1,000 refuelling stations around the nation, according to a road map published in 2016 by an advisory committee of the Society of Automotive Engineers of China.

Such an expanded network would be a game-changer for Wu Dong, who drives fuel-cell trucks for Qingliqingwei.

“The biggest drawback of driving hydrogen-fuelled trucks is the range,” said Wu. “We have to visit the refuelling station frequently. Otherwise, the truck runs as smoothly as one running on an internal combustion engine.”

In China’s commercial hub of Shanghai, an experiment has been ongoing for more than a decade to promote fuel cells. At the Anting refuelling station in Jiading district, first set up in 2007, five trucks were queuing up on a recent Wednesday to top up their tanks with liquid hydrogen. Each refuel took about 10 minutes to complete.

Shanghai’s government plans to expand its network of fuelling stations to 100, from the current four, capable of serving as many as 10,000 vehicles by 2023, People’s Daily reported in September, citing Zhang Jianming, deputy director of Shanghai Economy and Information Technology Commission.

And the government is throwing more subsidies at the sector, offering 240,000 yuan for every fuel-cell passenger car, and up to 400,000 yuan per truck. These direct subsidies came to halt in April. To better incentivise the industry to work harder on cost reduction to make hydrogen vehicles more affordable, the government announced a four-year programme in September to subsidise up to 1.7 billion yuan to teams of companies involved all along the chain, from materials to refuelling stations. To qualify, the minimum target is annual sales of 1,000 vehicles, each travelling 30,000 km on average, with annual output of 5,000 tonnes of hydrogen at no more than 35 yuan per kilogram.

“This policy offers extra support for domestic technological breakthroughs and manufacturing of core components,” said Western Securities’ analysts Wang Guanqiao and Yu Jiaying. “It especially favours the development of the long-distance and mid-to-heavy duty truck segments that electric vehicles can hardly penetrate.”

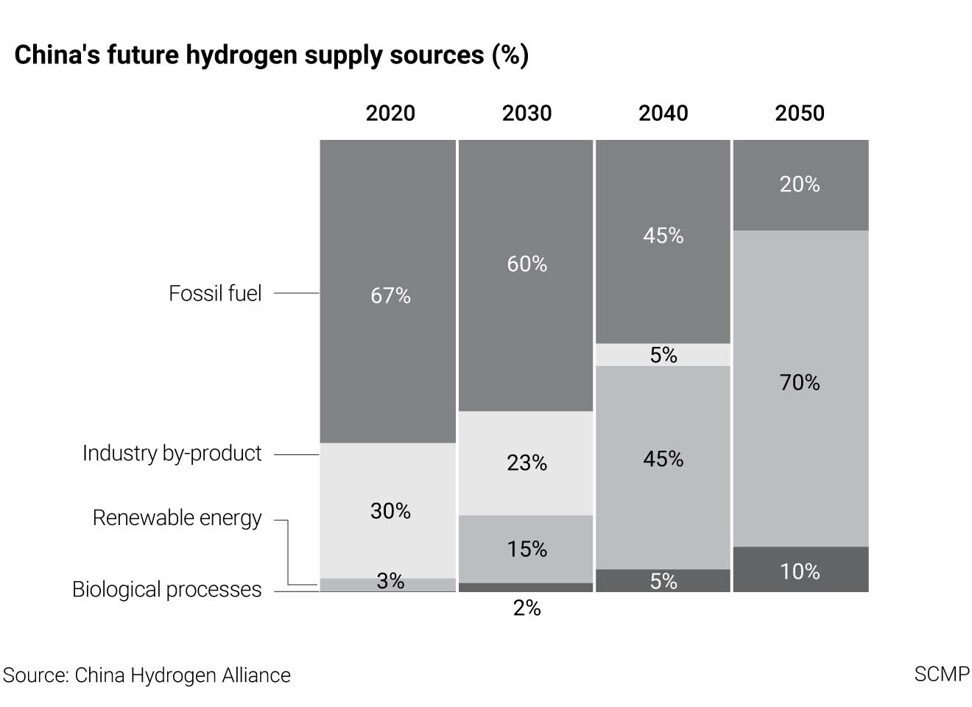

Hydrogen is currently produced mainly through chemical processes that break down coal or natural gas, at around US$1.5 for each kilogram of the gas. Once carbon emission quotas are handed down, costly facilities will have to be installed to store carbon dioxide.

It can also be produced through electrolysis, using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. If renewable power is used, the so-called “green hydrogen” produced is almost free of carbon emission, costing about US$3 per kilogram using renewable energy.

“Existing subsidies and the rental income are not enough to support a wide use of hydrogen-powered vehicles,” said Qingliqingwei’s vice-president Li. “We are expecting the governments to make more preferential policies [to promote hydrogen-powered vehicles].”

The average global production cost of green hydrogen is around US$4.7 per kilogram, with China as the cost-leader in the nascent industry, Sanford Bernstein’s analysts said. They estimated the global cost to fall to US$2.3 by 2030 and US$1.4 by 2050.

China is already the world’s largest hydrogen producer with annual output of 21 million tonnes, just over half used by oil refineries mainly to lower the sulphur content of diesel fuel. Output could triple to 60 million tonnes by 2050.

China is not the only country pursuing green hydrogen, whose global production could surge seven-fold by 2070 from last year’s 75 million tonnes, according to the International Energy Agency.

Several companies – most notably with projects in coastal desert regions in Australia and Saudi Arabia – are studying feasibility of green hydrogen and ammonia plants with targets to start production by the mid-2020s. They include the oil and gas giant BP and US industrial gas giant Air Products & Chemicals.

Fuel cells may also benefit from a mandatory nationwide carbon emission quota and trading scheme due in the next few years, which will result in higher costs of diesel and petroleum used by trucks.

For the pioneers and early adopters of hydrogen fuel cells, their day in the sun has finally arrived. Yu Zhuoping, dean of the College of Automotive Engineering at Shanghai-based Tongji University, was a partner with the Shanghai government in developing the city’s first refuelling station a decade ago.

“It was only a pilot programme to develop hydrogen-powered vehicles and refuelling stations at a rudimentary stage,” he said. “But since clean energy use is of strategic importance now with massive government support, we will naturally see a rapid growth of the industry soon.”

Still, subsidies are needed to promote the use of the clean energy.

“Without a scale, no businesses will be able to make profits or break even,” he said. “It will be some time before government subsidies to support the operation of the vehicles and stations are cancelled.”

This story, originally published by South China Morning Post, has been shared as part of World News Day 2021, a global campaign to highlight the critical role of fact-based journalism in providing trustworthy news and information in service of humanity. #JournalismMatters.