The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns humans are unequivocally warming the planet, and that is triggering rapid changes in the atmosphere, oceans, and polar regions, and increasing extreme weather around the world.

The IPCC released the Sixth Assessment Report on August 9th, 2021. The report from 234 scientists from around the globe summarized the current climate research on how the Earth is changing as temperatures rise and the impacts for the future. I was one of these scientists.

The facts about climate change have been clear for a long time, with the evidence just continuing to grow. The warning signs of climate change have been clear over the last decade, with each new emergency topping its precedent.

The earth as we know it has become radically altered by our misuse of fossil fuels and natural resources. Our lives and livelihoods are in danger of forever suffering from the consequence of our own actions.

Global temperatures are rising, producing more droughts and wildfires, increasing the intensity of storms, causing catastrophic flooding, and raising sea levels.

Rising seas increase the vulnerability of cities and the associated infrastructure that line many coastlines around the world because of flooding, erosion, destruction of coastal ecosystems and contamination of surface and ground waters.

Future sea-level rise will affect every coastal nation. But in the coming decades, the greatest effects will be felt in Asia, due to the number of people living in the continent’s low-lying coastal areas. Mainland China, Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand are home to the most people on land projected to be below average annual coastal flood levels by 2050. Together, those six nations account for roughly 75% of the 300 million people on land facing the same vulnerability at mid-century.

Global sea level is rising at a rate unmatched for at least thousands of years.

Global sea level is rising primarily because global temperatures are rising, causing ocean water to expand and land ice to melt. About a third of its current rise comes from thermal expansion — when water grows in volume as it warms. The rest comes from the melting of ice on land.

In the 20th century the melting has been mostly limited to mountain glaciers, but the big concern for the future is the melting of giant ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica. If all the ice in Greenland melted, it would raise global sea levels by seven metres.

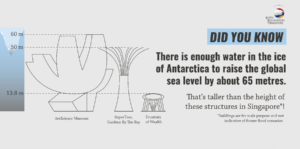

Antarctica is the existential threat to coastal nations. It is twice the size of Australia (over 20,000 times the size of Singapore!), two to three kilometres thick, and has enough water to raise sea levels by 65 metres. That is more than the height of the Singapore Art Science Museum and the Super Tree of Gardens by the Bay. If just a few per cent of the Antarctic ice sheet were to melt, it would cause devastating impacts.

Ominously, satellite-based measurements of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets show that this melting is accelerating. Greenland is now the biggest contributor to global sea-level rise. Greenland went from dumping only about 51 billion tonnes of ice into the ocean between 1980 and 1990, to losing 286 billion tonnes between 2010 and 2018.

That is a staggering 76 trillion gallons of water added to the ocean each year, which is equivalent to 114 million Olympic-size swimming pools.

Sea-level rise through 2050 is fixed. Regardless of how quickly nations can lower emissions, the world is looking at about 15 to 30 centimeters of sea-level rise through the middle of the century due to the long timescales response of the oceans and ice sheets to warming. Sea-level rise is expected to continue slowly for centuries, even under a stable climate. This so-called ‘commitment to sea-level rise’ leads to a long-term obligation to adapt to sea-level rise, which coastal policy and practice is only just beginning to recognize.

Beyond 2050, sea-level rise becomes increasingly susceptible to the world’s emissions choices. If countries choose to continue their current paths, greenhouse gas emissions will likely bring 3 to 4 C of warming by 2100, and sea level rise of up to 1 meter.

Under the most extreme emissions scenario, rapid ice sheet loss from Greenland and Antarctica is possible leading to sea level rise approaching 2 meters by the end of this century. At this point sea-level rise is not an existential threat but a reality to coastal nations such as Singapore.

But there is hope to survive sea-level rise.

The IPCC report has shown a growing understanding of the causes of climate change and their solutions.

A 2 C warmer world, consistent with the Paris Agreement, would see lower sea level rise, most likely about half a meter by 2100.

What’s more, if the more the world limits its greenhouse gas emissions, the chance of triggering rapid ice sheet loss from Greenland and Antarctica is much lower.

But time is running out to meet the ambitious goal laid out in Paris Agreement to limit warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

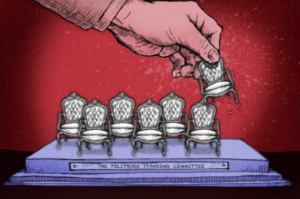

We must hold our elected official accountable to the promises they have made on climate change. Indeed, we may require reductions far more than those that have been pledged by nations in the run up to COP26, the United Nations climate summit to be held in Glasgow in November.

Fortunately, attitudes across the world towards climate change have shifted in the last decade. Where once there was ignorance, inattention, and disbelief about climate change, now there is concern.

Individually, rather than depriving ourselves, we should instead be adding to our lives to contribute to the fight to tackle the climate emergency. These can include things like volunteering, activism, and spreading awareness to other people about the effects that climate change can have on our lives. All these positive solutions coupled with attempting to live a more sustainable life, can make all the difference.

Technological advances are also a cause for hope. Solar and wind energy and battery technology are now far cheaper, and their efficiency is getting better and better. New technologies, including artificial intelligence, now also offer the prospect of huge improvements in the energy efficiency of transport systems, building operations, manufacturing processes and food production.

Ways to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere also offer hope, not only of reaching net zero, but in eventually reversing climate change.

The planet’s oceans, forests and grasslands take up huge quantities of carbon dioxide through photosynthesis, much of which is stored in plants or in the soil, creating major global carbon sinks.

By preserving and expanding forests, these sinks could be made larger. Taking greater care of oceans and land is not only important for preserving biodiversity but is also a key part of climate change mitigation.

I believe that, for all the challenges that we face, climate change is the one that will define the contours of this century more dramatically perhaps than the others.

Surviving sea-level rise is going to change our lives; it is going to change the way we regard ourselves on the planet; it will lead to a happier, more equitable way of life for all of humankind.

Only then can we leave behind a world that is worthy of our children, where there is reduced conflict and greater cooperation – a world marked not by human suffering, but by human progress.

This story, written by Professor Benjamin P. Horton, Director of the Earth Observatory of Singapore, Nanyang Technological University, has been shared as part of World News Day 2021, a global campaign to highlight the critical role of fact-based journalism in providing trustworthy news and information in service of humanity. #JournalismMatters.