China’s renewable energy industry is poised to lead an unprecedented industrial transformation that would turn the world’s largest greenhouse gases emitter into a carbon neutral country in less than four decades, at an estimated cost of US$5 trillion.

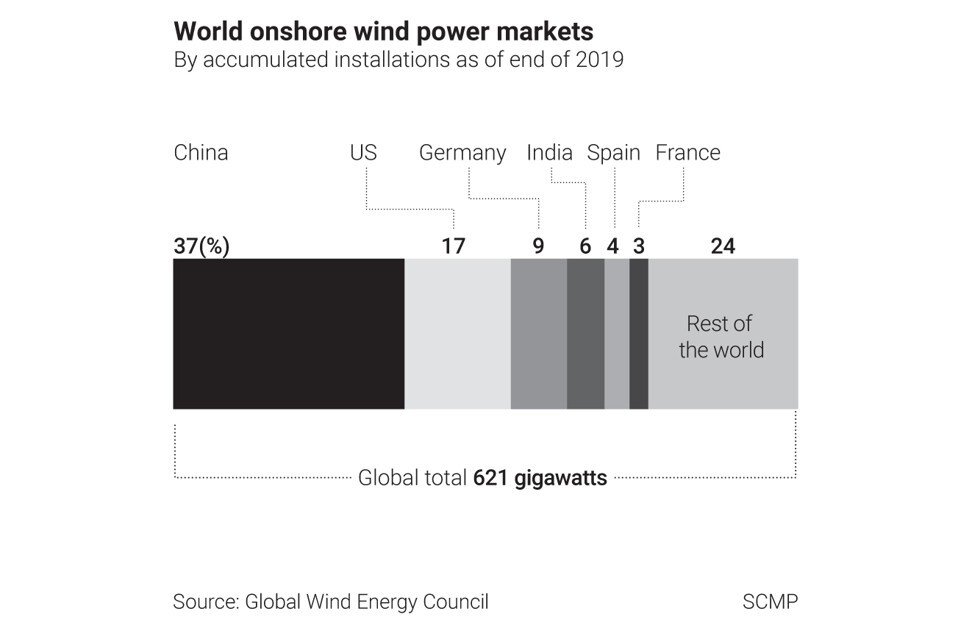

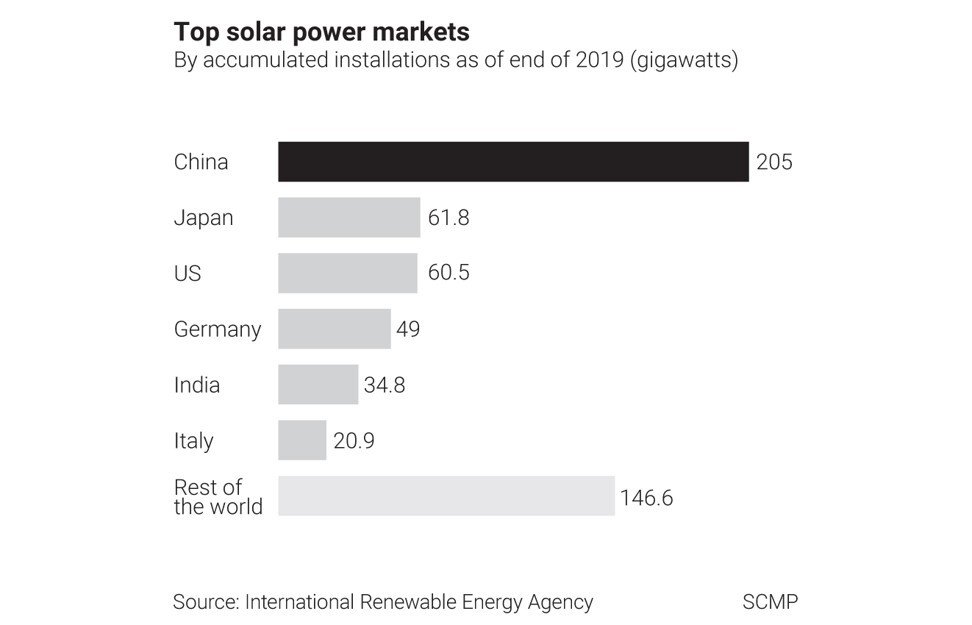

The nation, already the biggest global producer of hydro, wind and solar power, will have to curtail most fossil fuel production and drastically install more equipment to harness nature’s energy to meet the 2060 carbon neutrality goal pledged by President Xi Jinping to the United Nations General Assembly in September.

The uncertain journey to carbon neutrality – where residual emission is fully offset by amounts captured from the atmosphere – will be a gradual and at times painful process, because it transforms livelihood in the tens of millions, involving trillions of dollars in funding, analysts said.

“The most challenging part of the shift is not the investment or magnitude of renewable capacity additions but the social transition,” said Prakash Sharma, head of Asia Pacific markets and transitions at resource consultancy Wood Mackenzie in London. “[Slashing] coal capacity will result in loss of coal mining jobs, affecting provinces that depend on its revenues and employment generation.”

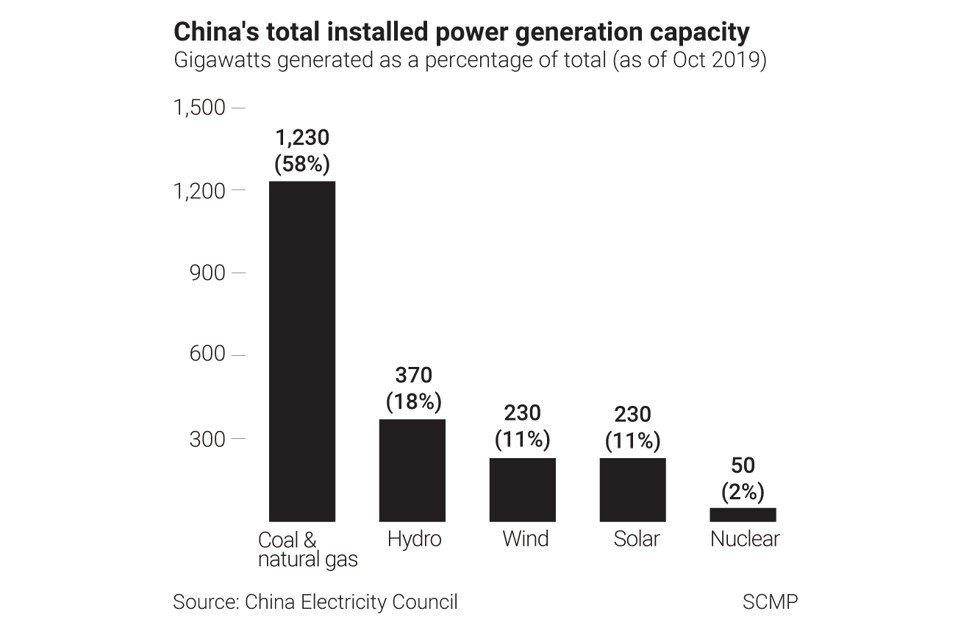

To meet the goal, China must cut its reliance on fossil fuel to 25 per cent by 2050 from the current 85 per cent, removing much of the rest with carbon capture and storage technology, according to Sanford Bernstein’s analysts Neil Beveridge and Wang Lu.

In the makeover scenario, natural gas – with a carbon footprint half of coal and a quarter less than petroleum – is the only fossil fuel that will grow in the energy consumption mix to 14 per cent from 8 per cent. Coal’s contribution will shrink to 3 per cent from 57 per cent, while oil will decline to 8 per cent from 20 per cent.

Solar energy is forecast to be the biggest winner, rising from 1 per cent to 22 per cent and become the biggest energy source, followed by wind power at 17 per cent from 3 per cent. Nuclear energy’s weighting could quadruple to 8 per cent, and hydrogen will grow from almost zero to 11 per cent.

William Shen, a Chinese journalist, paid 200,000 yuan in 2017 to install a 100-square metre (1,076 square feet) solar panel on his roof in Wujiang city in Jiangsu province. He sells the power generated from his 15-kilowatt solar panel to the local electricity grid, receiving between 1,000 yuan and 2,000 yuan every month, based on the local tariff rate of 0.42 yuan for every kilowatt-hour

“It was not a good deal in business terms,” Shen said. “But I still think the money is worth of it because using clean-energy is of great social value.”

China’s energy transition will create millions of jobs in renewable energy. Already the leading equipment producer and the largest market, China employs 2.2 million people in solar power, more than half of the industry’s jobs worldwide, according to the China National Renewable Energy Centre. Chinese wind farms and factories making wind mills and turbines employed 518,000 workers, or 44 per cent of the global total.

Millions of jobs are at stake for coal mines, where the top 10 miners typically employ between 80,000 to 160,000 workers. China’s largest 50 miners, producing 71 per cent of the nation’s coal, had 4.15 trillion yuan (US$634 billion) in combined revenue last year, according to China Coal Industry Association.

Shanxi province, the hardscrabble, landlocked region in northern China, is the nation’s largest coal production area, earning more than half of its state-owned industrial sector’s output from coal-related activities over the past three years. Coal-related assets make up 36 per cent of Shanxi’s state-owned assets, Guosheng Securities said.

Over the next four decades, many coal mines and thermal power plants may have to shut, unless the industry can slash the cost of capturing the carbon dioxide emissions.

The capture, usage and storage of carbon, a potential game-changer for the long-term decarbonisation in fossil fuel industries, is still nascent in China and is uneconomical, said HSBC’s head of Asia utilities research Evan Li. These carbon capture facilities would triple the cost of coal-fired power, he said, citing data from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis in Ohio, which said in July that there is “no commercially viable examples of … [such projects] … anywhere in the world.”

The world will have to look to the Chinese government’s 14th Five-Year Plan from 2021 to 2025, due to be published next year, for details of how every energy-intensive industrial segment should work toward the 2060 target. A necessary first step is the long-awaited nationwide plan for pricing, allocating and trading carbon emission quotas, which will affect the biggest emitters – most notably the power sector – when it starts within the next five years.

Despite the fanfare around Xi’s pledge, China’s transition to an economy with low energy intensity is in danger of stalling, as the government doubled down on stimulus policies this year and in 2021 to avert a stalling economy, especially with the coronavirus pandemic still raging around the world.

About 31GW of power plant capacity was approved in the 12 months until October, according to the China Electricity Council, while 19.7GW of coal-fired power plants were given the green light by local authorities in the first half, the biggest investments in recent years.

“Investments in renewables continue, but signs of a return to coal are emerging, a tendency that could strengthen as post-pandemic geopolitics push energy security up the policy agenda,” said S&P Global Ratings in September. “To dig the economy out of its Covid-19 low, planners are approving more infrastructure. Policymakers are stimulating heavy industry, leading to greater energy intensity.”

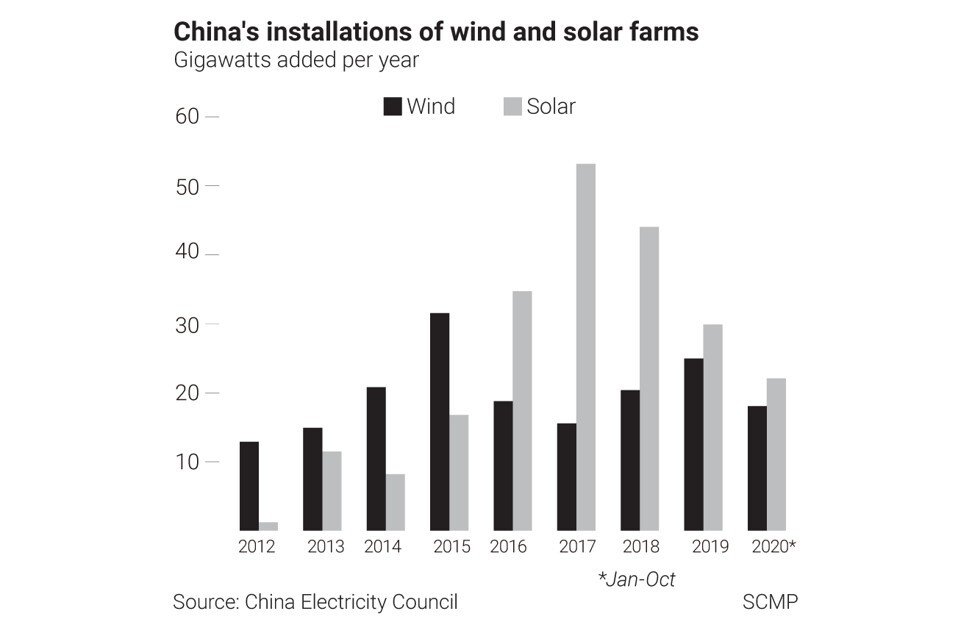

The growth prospect for renewable energy will face short-term bottlenecks. The wind power equipment industry urged the Chinese government in October to raise the average annual wind farms installation target in the next five years to 50GW, rising to 60GW after 2025, more than double the 24GW installed last year.

Such a pace may be beyond reach, as Beijing will stop subsidising new onshore wind farms and solar projects from 2021, said Daiwa Capital Markets’ analysts Dennis Ip and Anna Lu. There are also limits in the ability by power grids to absorb the intermittent and variable output from these sources.

“It is hard to achieve such an aggressive target at least in the next five years, as wind power has yet to achieve large-scale grid parity while China will halt subsidies for new installations from next year,” they said. Parity, where the cost of generating wind power matches benchmark coal-fired electricity tariffs in most regions, won’t be reached until 2022 or 2023, they said.

For solar farms, the generation cost could drop 40 to 50 per cent by 2025, enabling grid parity to become the norm, said HSBC’s Li. Still, a wrench has been thrown into the works by the shutdown of GCL-Poly Energy’s plant in Xinjiang, disrupting the production of polysilicon used in solar panels, causing the price of the raw material to soar 60 per cent in two months. A lack of new capacity until 2022 will put a limit to solar equipment, he said.

“We invest for the future, but it is apparent that there is a long way to go before solar energy is widely used in China,” said Shen, who has solar panels on his roof in Wujiang. “Few people are able or willing to spend 200,000 yuan as an initial investment. A lot more public money needs to be poured into solar energy to encourage wide use. The government should invest for the future too.”

Another constraint reining in growth has to do with financial resources.

The government’s decision to stop subsidising wind and solar tariff – financed by a surcharge on electricity bills – was intended to shift the cost burden of renewable energy to coal and gas-fired power producers. The shortfall in the state fund that pays for the subsidies is expected to triple to 300 billion yuan this year from 2018, said China Wind Energy Association’s secretary general Qin Haiyan, who proposed special government bonds to plug the hole.

Developers of renewable projects have to wait between three to five years to receive their subsidy payments, severely constraining their capacity to invest in new projects, especially for privately-owned firms that lack the deep pockets of state-owned companies.

GCL New Energy, a unit of the Jiangsu province-based GCL, was owed 9.2 billion yuan of state subsidies in June, forcing it to appoint a financial adviser to find funds to repay US$500 million of debt due in January 2021. The privately owned company was forced to sell 1.7GW, or a quarter of its projects, for 2.9 billion yuan, as its net debt surged to nearly four times its shareholders equity.

Help may be on the way. An incentive called the “green certificate” trading system, tried on a voluntary basis since 2017 to fund carbon reduction projects, may be rolled out soon, said Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) strategy director Zhao Feng.

If implemented, renewable energy quotas would be imposed on power generators and major energy consumers, which must buy certificates from renewable energy generators to make up for any production or consumption shortfalls. It was intended as a replacement for subsidies.

Meanwhile, the rush in installing wind farms is expected to continue until year-end to meet the deadline to qualify for subsidies, bringing onshore installations to 30GW this year, GWEC said.

“There are challenges in the supply chain, but … these can be overcome by finding new ways of doing things and new sources of supply,” said GWEC’s chief executive Ben Backwell in Brussels.

With additional reporting by Daniel Ren in Shanghai.

This story, originally published by South China Morning Post, has been shared as part of World News Day 2021, a global campaign to highlight the critical role of fact-based journalism in providing trustworthy news and information in service of humanity. #JournalismMatters.