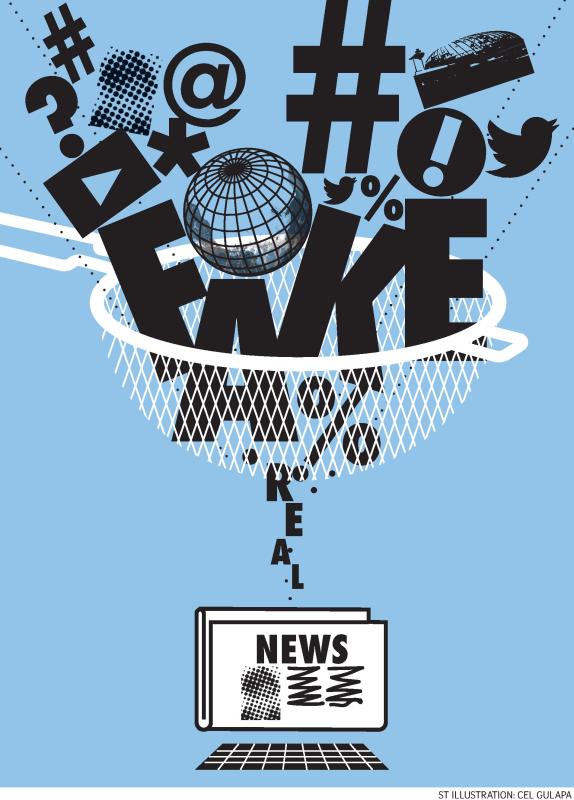

Helping readers sift the real from the fake

Warren Fernandez

President, World Editors Forum

A video that went viral caught the dramatic moment when a ceiling in a busy shopping mall came crashing down. Screams rang out as shoppers scurried to safety.

But no, this scene did not play out at Singapore’s newly opened Jewel Changi Airport mall, as alleged in a post that went round last week.

Rather, the incident took place recently at Shanghai’s Vanke Mall, as reporters from this newspaper found out. We were alerted to the video by an anxious reader who turned to us to find out if the video posting was true or make-believe.

Such online falsehoods are a public menace of our times. A growing number of people say they are concerned about them and find it increasingly difficult to tell real news from fake. What is worse, studies show that fake news gives rise to more shock and awe, and so spreads more rapidly than factual news reports.

Lamentably, things look set to get worse, with the emergence of new technologies, such as deepfake. This allows video images to be manipulated such that words can literally be put into the mouths of prominent personalities. And with the technology getting more sophisticated and less costly to produce by the day, seeing might soon no longer be enough for believing.

So, this is where professional newsrooms will have to increasingly play a role – in helping the public separate fiction from fact.

Of course, newsrooms can’t fight fake news on their own, and this task will have to be one shared by many. Yet, that is no reason for each of us not to pitch in and do what we can.

At the very least, our aim should be to raise public awareness of these efforts to mislead, and encourage audiences to pause and question what they read before sending it along.

Yet, such overtly fake news, spread out of malice or mischief, is just one form of online falsehoods. Another version of this was on full view last week in the tweets from none other than the President of the United States, Mr Donald Trump.

Well aware of the power of his online outpourings, he ordered American firms to relocate from China and bring their factories home, sending shock waves through global financial markets.

Perhaps alarmed by the reaction, Mr Trump dialled back the next day, saying he had “second thoughts” and disclosing the “very good calls” he received from unnamed leaders in Beijing, who had apparently reached out to try to put the stalled talks on the Sino-US trade-technology-currency spat back on track.

Sceptical reporters delving deeper into this, however, soon discovered that Chinese officials were unaware of any such conversations, raising doubts about whether they had indeed taken place.

Well, thank goodness for dogged reporters, for without them, newsmakers everywhere would feel free to manipulate and mislead with impunity.

Reporters digging deep, to uncover the facts, convenient or otherwise, are a pre-requisite for meaningful discussions. For public discourse can only be conducted if those on opposing sides might agree on some of the basic facts they are discussing.

Reasonable debate grinds to a halt if those involved insist not only on their right to hold a different opinion but also having their own “alternative facts”. Policy discussions are then reduced to shouting matches, catchy soundbites, empty slogans or bold lettered tweets.

The consequences of this are increasingly clear: growing mistrust, polarised societies, ill-informed electorates and divided parliaments, as is now playing out in the land of William Shakespeare, that painful-to-watch, long-running, tragicomedy called Brexit.

Indeed, research cited in the Caincross Review, an independent commission set up by the British government to study how to secure a sustainable future for quality journalism, pointed to the “dire democratic consequences” that might arise from a lack of reporting on public authorities.

It went on to note further that there was a “clear link between the disappearance of local journalists and a local newspaper, and a decline in civic and democratic activities, such as voter turnout, and well-managed public finances”.

Here, again, professional newsrooms have a role and a mission. For it is their job to seek out information and try to establish the facts, so as to enable, and facilitate, the public debate that might follow.

Information, however, does not always flow freely. It has to be sought out, verified, cross-checked against many sources, interpreted fairly and objectively, and put in proper context.

This is what professional journalists in established newsrooms do. It is laborious work, time-consuming, and requiring considerable resources to do well.

Ensuring that this public good is delivered is in society’s interest, as the Caincross Review concluded, adding that this was not something that can just be left to the narrow commercial considerations of media moguls or business conglomerates.

Securing the future of public-interest journalism is especially important amid the growing cry from citizens for help in sifting out the real from the fake in today’s super-abundance of information.

Taking up this issue in a thoughtful essay, titled Back To The Future Of News, Professor Charlie Beckett, director of the London School of Economics’ journalism institute, Polis, argued that fake news is both a bane, and a boon, for credible journalism.

He said: “The fake news crisis is good news for credible journalists. The more reliable and accountable news brands have seen a sharp rise in people consuming their content and even paying for subscriptions. When there is an abundance of questionable material out there, people often turn to more trustworthy sources.

“Journalists have a moral opportunity here. It is also a business opportunity. One option is for journalists to produce clickbait, to pander to the worst impulses of those people attracted by fake news. But there is also an option for journalists to be better curators, filters, or guides in the dark forest of overabundance. Journalists can be much better at identifying what is credible, verifying what is believable and helping citizens get the evidence they need.

“Journalists must still do quite traditional things: be critical, bust myths, give context, be accurate. Their job is also to say challenging things and take on those in power or positions of authority. However, they should also have a sense that they are contributing to ‘the good life’ and to a ‘good’ society.

This is not some woolly idea. It is a practical service that says that journalism can help people to live healthier, happier, more enabled lives as individuals and in communities. Good information is good for us, and journalism can help provide this.

“This is about journalists empowering the public, not themselves.”

But just how are societies to ensure that this public-interest journalism continues to be available, given the major disruptions taking place in the media industry, with audiences drifting online, and the bulk of digital advertising being mopped up by the big tech players?

Well, the ever-insightful Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari has some interesting answers in his latest bestseller, 21 Lessons For The 21st Century. His advice to those grappling with the challenge of making sense of an increasingly complex and confusing world is simple: Start by seeking out the best reports and information, make the effort to read them, and be prepared to pay for them.

“If you want reliable information – pay good money for it,” he says.

“If you get your news for free, you might well be the product,” he adds, pointing to how technology companies mine data on how audiences spend their time online, and use this information to rake in huge profits by serving up targeted advertising.

He adds: “Supposing a shady billionaire offered you the following deal: ‘I will pay you $30 a month, and in exchange you will allow me to brainwash you for an hour every day, installing in your mind whichever political and commercial biases I want.’ Would you take the deal? Few sane people would.

So the shady billionaire offers a slightly different deal: ‘You will allow me to brainwash you for one hour every day, and in exchange, I will not charge you anything for this service.’ Now the deal suddenly sounds tempting to hundreds of millions of people. Don’t follow their example.”

Indeed, please don’t.

Instead, you would do better to support the 30 newsrooms from around the world which are coming together later this month to mark World News Day (WND). To be held on Sept 28, the day is meant to celebrate the work of newsrooms and the contributions they make to the communities they serve.

Together, these newsrooms plan to showcase their efforts to expose corruption, uncover human and drug smuggling, check sexual harassment and exploitation, question and improve public policies, or celebrate the work of various groups which are striving to uplift and inspire others in the community. These reports will run on the platforms and pages of all participating media organisations on the day, as well as on the WND website at www.worldnewsday.org

Organised by the World Editors Forum, a professional network within the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (Wan-Ifra), the theme for World News Day is clear and simple: Real News Matters.

It does matter, not just to journalists and newsrooms, but more importantly to you, because the best news reporting is always about developments and why they matter to the reader – to you, your family, your society and your world. Do join us in marking World News Day on Sept 28.

The writer is the Editor-in-chief at The Straits Times