To mark World News Day on September 28, 2022, the World News Day campaign is sharing stories that have had a significant social impact. This particular story, which was shared by The Daily Star (Bangladesh), was published on August 30, 2022.

“How are our loved ones? Are they eating well? Are they being tortured? Are they… alive?” These questions haunt the family members of the victims of enforced disappearance as they spend agonising weeks, months and years, holding out hope against all odds.

At least 522 people have become victims of enforced disappearance between 2009 and 2018 in Bangladesh, cite various human rights organisations.

Most survivors who come back home after being released from their forced captivity stay away from the public eye, never revealing where they were or who took them. A March 2022 study by the Centre for Governance Studies (CGS) tracked down cases happening between 2019 and 2021 and found that of the 30 percent of victims that were released, or officially arrested and thrown in jail, not one spoke up.

But on condition of anonymity, five such survivors answered the questions asked most pertinently by their loved ones.

While their families search every alleyway, survivors say that they lived right around the corner in the capital city.

All testimonies by survivors point to at least two separate centres in Dhaka city, allegedly run by a security force and a law enforcement agency, and a third centre in a southern district.

According to the claims made in the interviews, the centres are fully fledged illegal prisons, running on taxpayers’ money meant for maintaining law and order and protecting the country.

The Daily Star is refraining from mentioning the names of the units to protect the anonymity of the sources.

The details described by two of the survivors correspond with each other and point to one centre – let’s call it Centre “U” – while three other survivors all gave identical testimonies of the second centre. Let’s call it Centre “C.”

The survivors were kept in the centres for periods ranging from two months up to one and a half years. Their years of detention spanned between 2015 and 2020.

Four of the survivors were picked up for political reasons and their social media activities, while one survivor, who had been kept in Centre “C,” was a case of mistaken identity.

All of the survivors were picked up from Dhaka – this corresponds with the CGS study that found that over a third of the cases happened in just the capital city.

At Centre “U,” the victims described harsher, inhumane living conditions and torturous interrogations, while the victims at Centre “C” described a meticulously designed prison equipped to cater to any and all needs of the detainees.

Both, however, serve the singular purpose of holding a person against his will in solitary confinement, arbitrarily and illegally, for an endless period of time, not knowing whether he will be released or see the end of his life.

Both detainees from Centre “U” described being held in cells roughly 2.5 feet in width, four feet in length and five feet in height — “such that one cannot lie down, or stand up. One must always be half-sitting or half-lying.” The cells had three concrete walls and a prison cell door with rungs.

One of the detainees was kept there for four months before being transferred to a southern district, while another detainee was kept there for a little over a week before being transferred to a bigger cell within the same centre. Their detention periods were five years apart.

Both detainees spoke of being blindfolded and handcuffed during the entirety of their stay at Centre “U”.

“It was very dark, but I was also blindfolded. Everyone gets blindfolded. The cell was two floors down under the ground. They strip you down to your underwear. They give you a lungi. The lungi was given many, many hours later after stripping,” said one detainee, describing the initial moments of his captivity.

“Our hands were cuffed at the back for the whole duration of our captivity, except when it was time to eat and when we went to the bathroom,” he said. The continuous handcuffing was such that a guard took pity on them and used to secretly open their handcuffs at night.

“There was an uncle, an old guard; he used to uncuff all our hands after midnight for a few hours. We could then open our blindfolds. I got him on three nights during my stay,” said the detainee. He was held at Centre “U” for less than three months.

The detainee said that he was transferred to a bigger cell a week into his arrival to Centre “U”. “I climbed metal staircases to my second cell. This place had a bigger room, but it was extremely hot and there were lots of mosquitos. The rooms had stand fans – they were switched on only occasionally. They knew exactly how much would be needed to keep us alive,” he described.

“The floor was of broken cement. And we were made to sleep on the floor without any bedding. I was given a bottle of mineral water and I used to use that as a pillow under my head. It could get so cold at night on the floor…” he recalled.

Another detainee who stayed at the centre for less than six months said, “For as long as I was in that centre, I was kept blindfolded and handcuffed. The centre was probably three storeys underground.” He said that he had realised this because when he was being transferred to another centre, they made him climb up three storeys and then he straightaway entered a vehicle kept at that level.

Similar to the first detainee, his cell too was too small to lie down in, and he sat up for months on end.

Both the victims said they had counted the number of detainees by the noises made by plates and doors during meal distributions.

The first detainee said he remembered counting 12 cells, one facing the other. “I counted when my eyes were opened for the first time by the kind guard, and I saw the cell opposite to mine. I also counted by the clicking of cell doors when they used to give us food.”

The second detainee said, “There were about 14 of us in that long hall. I counted by the noise of the metal plates hitting the floor during mealtimes.”

Similarly, even though their detention periods were spaced five years apart, they were both tortured during interrogation.

“I was interrogated for six hours. Every part of me was tortured. They used movie-like torture methods. They used something to give intense heat from up top. I was bleeding from the nose because of the torture. By the time they took me back to my cell, I was unconscious,” said one.

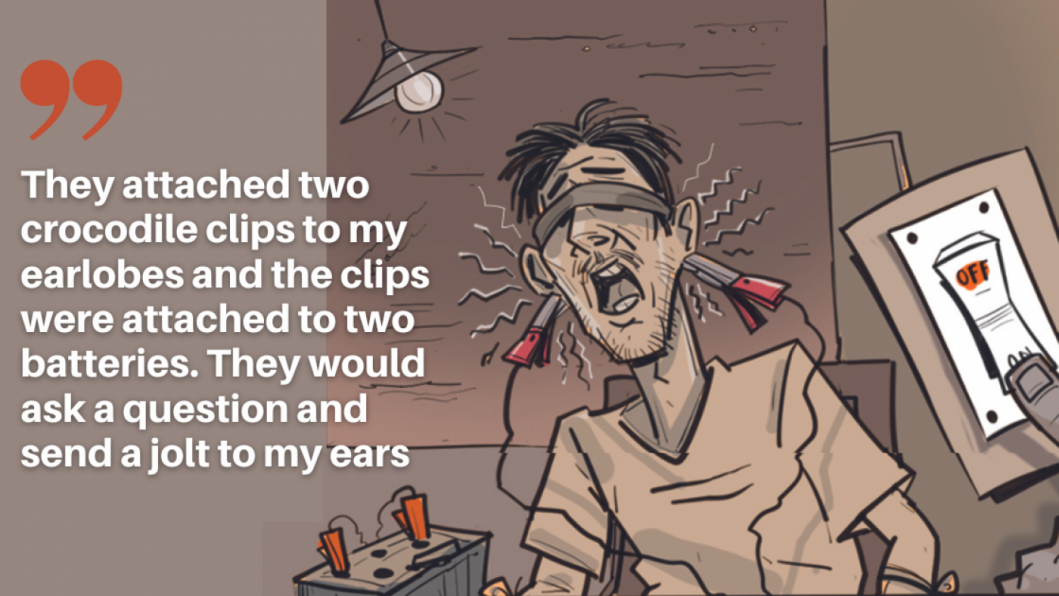

Another claimed, “I was made to sit in a wooden chair with ankle bindings and wrist bindings. They attached two crocodile clips to my earlobes and the clips were attached to two batteries. They would ask a question and send a jolt to my ears. They kept threatening that if I did not cooperate, they would attach the clips to my genitals. I urinated because of the torture.

“I would be beaten if I tried praying. They used to say that a sinner like me need not pray,” he shared.

He also described another method of torture at a second centre. After his stint in the capital city, he was taken to another centre outside the capital towards the south. The Daily Star is refraining from naming the district to protect the detainee.

“It took many hours to reach that place. On our way to that district, I heard the names of the areas from the bus conductors crying out for passengers, and so I know where I was taken. The place was not too far from a launch jetty, because I kept hearing the whistles of the ships during my stay there,” he described.

The torture method in that centre involved force-feeding. “They would bring buckets containing several kilograms of beef. ‘You will have to eat half of this,’ they would tell me. For each meal, we were given six eggs,” described the detainee. “You have no idea how much money they spend behind each detainee.”

At that particular centre, the walls were of corrugated tin and the detainees were kept in what looked like large animal cages. “At least I could stretch my legs inside. Here, instead of having my hands locked in the front, one hand was put in a cuff, and the cuff was tied to a long rope attached to a hook outside the cage.” There were four cages inside the long room, he said.

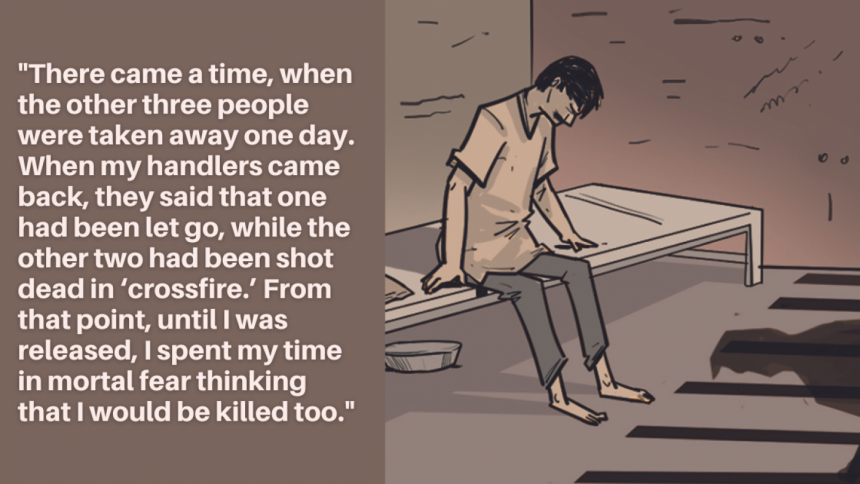

“There came a time, when the other three people were taken away one day. When my handlers came back, they said that one had been let go, while the other two had been shot dead in ‘crossfire.’ From that point, until I was released, I spent my time in mortal fear thinking that I would be killed too,” he stated.

The threat of “crossfire” was used as an interrogation tool and torture method. “I was taken to a large highway in the city – I was blindfolded and cuffed so I don’t know which one. When we reached the area, everyone got out of the car, leaving me. I could feel a person getting in. He asked me questions about my political allegiance. At one point during the questioning, I was dragged out of the car and asked to run. I was afraid of being shot from the back, so I did not run and just stood in my spot,” he said.

Both the detainees described the use of large machines as noise-cancelling techniques to drown out the voices of the people inside.

One detainee said something like a large generator operated at all hours. “I started bleeding from the nose and throat because of the noise,” he said.

The other detainee described extremely loud music being played at certain times. “It would make my head hurt.”

He also said he would have to shower in the middle of the night. “I was bare-chested and had only one lungi. Every time I washed it, I would have to wear the wet lungi until it dried. I am prone to the cold and it was pure torture,” he said.

Five years later, laundry systems at the centre were seemingly improved. The other detainee described, “They had a collection of lungis and T-shirts that would get rotated among the inmates. We could wash our T-shirt and lungi and leave it to dry in the washroom and be handed a replacement,” he said.

Both the detainees cut their hair and shaved only once during their many months of detention, just prior to release.

Centre “C”

The three detainees of Centre “C” described better facilities and did not report torture.

All detainees described the centre as a fully functioning outfit with its own kitchen, capable of cooking feasts, a barber’s room, a doctor’s room, fully stocked bathrooms, rooms furnished with beds and blankets, high commode toilets and even books for the detainees to read.

Some of the detainees would respectfully be addressed as “sir” or “uncle.”

But none of that takes away the fact that they were being held against their will for up to two years, while their families wondered if they were dead or alive.

“My room had an iron bed, and I was given four blankets to make a mattress. A light bulb shone at all times, and an exhaust fan whirred at the corner of the door,” the detainee said.

The man, an ordinary professional, had been picked up from his home for his social media activity, supporting opposing political thoughts.

A few days into captivity, he asked for a book to read. “They brought me the second part of a book, and when I asked for the first part, they said another detainee was reading it. Later on, when I asked for another specific title, they had that brought in from a bookstore,” he said. “Just the first page with the name of the store was torn out.”

The detainees were not handcuffed or blindfolded inside their cells; one probable reason for this could be the fact that their cells had two doors – one with rungs like a jail cell, and another solid door – and so they could not see anything outside.

“The food was slipped in through a trap door at the bottom of the door. I used to wash my hands inside the room,” he said.

Every time they had to go out of their cells, however, a black hood cover had to be worn and their hands were cuffed. This was during bathroom visits.

“Once the hood slipped, and my handler did not bother putting it back on. I saw a kitchen to my right, and a woman cooking in there,” he said.

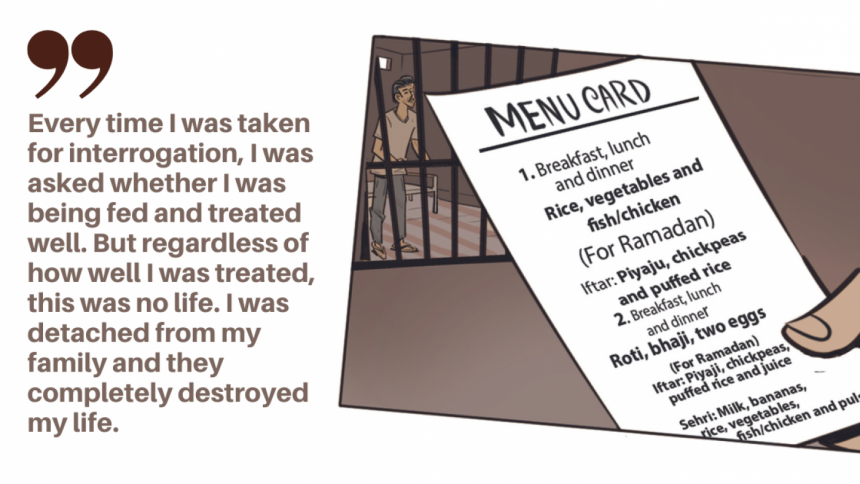

All food arrived hot and the detainees had a selection to choose from. “During lunch, I was given shaak, tilapia fish, two eggs and daal. When I told them that I didn’t want to eat farmed fish and egg, they brought me beef,” said one detainee.

“During Ramadan, I used to be given hot milk, a big banana, rice, vegetables and proteins during sehri, and fruits, juices, fried snacks, chickpeas and sweets for iftar,” he described.

Several detainees described that during special days, they used to get feasts – parathas, vermicelli, rice and nut desserts for breakfast, and rich preparations of beef and chicken and rice for meals.

“Every time I was taken for interrogation, I was asked whether I was being fed and treated well. But regardless of how well I am treated, this is no life. I was detached from my family and they completely destroyed my life,” one detainee described.

As a guard once said to a detainee, “Over here, you will get whatever you ask for – unless you ask for something I can’t give you.” That something would be letting their friends and families know they were safe, learning the reason for their enforced disappearance, or knowing their fates.

The detainees described two types of rooms: one facing a wall, and the other facing a balcony.

The detainee whose cell faced a wall said that the solid door of his cell was kept open most of the time, but was closed every time someone had to be taken to the bathroom so that he could not see them. This detainee was taken in as a case of mistaken identity.

Another detainee whose cell faced a balcony said he had a small ventilator window, through which he could catch glimpses of the outside world. His cell was on the ground floor.

“Through a small grilled ventilator, I saw a jackfruit tree bearing fruit, and watched the fruit grow. I saw the rain, I heard birds. I used to hear a boy playing a guitar and his sister complaining to his mother about him,” he recounted. Right beside this normal, beautiful world, he lay hidden in his hole of solitary confinement.

“I once knocked on the wall to try and talk to the cellmate next to me, but there was no response. The walls were about 10 inches thick and very high,” he described.

The detainee counted every single day. Using a tiny piece of wood, he would etch the dates at the bottom of the wall. The national days helped him keep track of dates – when he used to hear nationalistic or patriotic songs play outside, he would realise what date it was, he said.

“Past inhabitants had written many things on the wall – from poetry, to Arabic writing, to Hindu religious symbols. One day, a few men came in and painted all over them,” he described.

Once he slipped and fell in the bathroom, and needed to go to a nearby hospital for an X-ray.

“They put a hood over my head and led me into a vehicle. That was the first time I felt the sun on the hood covering my face. I heard rickshaw wallahs yelling at each other. I thought of pulling up my hood and running away, but then I thought they would shoot me or catch me. If they caught me, I would not be getting the comforts in my cell. I held onto the officers’ reassurance that when the time came, I would be home again,” he said.

Another detainee described how he could hear a lot of crying from the next cell. “If he cried too much, he’d be taken somewhere. Then he’d come and sleep for a long time,” he said.

The solitary confinement was what weighed hard on some of the detainees interviewed by this correspondent, such that they would go into lengthy details about the most mundane conversations they had with their guards – their only point of contact with the outside world.

Some of them also spoke respectfully – almost fondly – about the handlers who treated them with the minimum dignity, almost as if glossing over the fact that the handlers, too, are captors complicit in this gross human rights violation.

It would be all too easy to discredit their statements as lies, since the interviewees are not revealing their identities. But upon hearing their testimonies, the question arises: Who would want to risk going back to that?