This story was originally published in The Irish Times.

Interview five

The interview room at Finglas Garda station, in north Dublin, is not a nice place to be at the best of times.

It is small, stuffy and not designed for more than three people to use comfortably for any length of time.

By 2.30pm on May 25th last year all five of its occupants were feeling stressed. Among them was a 13-year-old boy who had been answering questions for nearly 10 hours over two days.

His mother, who in the first interview had sat beside the boy, holding his hand, had moved her chair farther away. She appeared to become more distressed by every new question put to her son.

The boy’s solicitor, who had remained silent for most of the process, had begun to clash with the interviewing gardaí more frequently over their questioning.

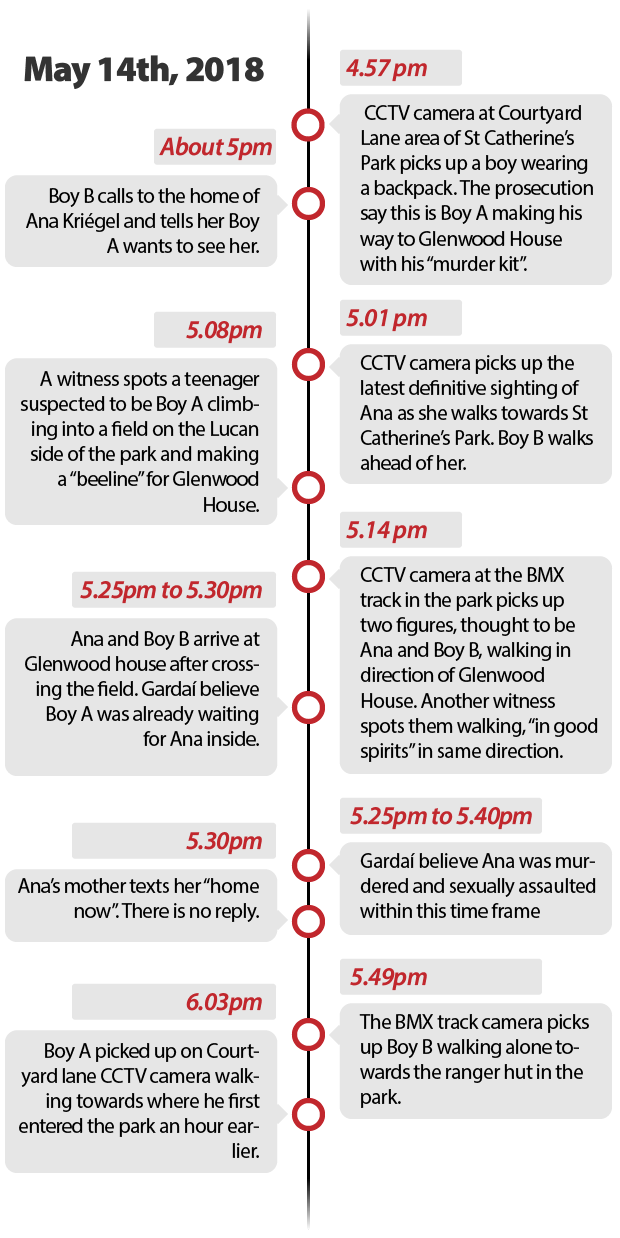

For the Garda detectives in the room, Donal Daly and Damien Gannon, the stress came from the knowledge that they had only a few more hours to get the boy, who would later become known to the public as Boy B, to reveal how 14-year-old Ana Kriégel had been murdered, 11 days earlier.

The investigators had a mountain of forensic evidence, but it was all against Boy B’s coaccused, and one-time best friend, Boy A. They knew Boy B was present when Ana died, and they knew he had played a role in bringing her to the abandoned house where she was killed. They also knew there was a big difference between knowing something and proving it.

It had been an exhausting process. Slowly but surely the detectives’ questioning had caused the boy to revise his account of the day of Ana’s murder.

Boy B had started the interview process the day before by repeating what he first told gardaí the previous week: that Boy A had asked him to call to Ana’s home, in Leixlip, just outside Dublin in Co Kildare, and bring her to him in St Catherine’s Park, so they could talk. And that he left Ana with Boy A before going home to do his homework.

As part of their investigation, gardaí had examined more than 700 hours of CCTV footage from the area around where Ana disappeared. Daly and Gannon put it to Boy B repeatedly that the route he claimed they took that day in no way matched what was captured by the cameras in and around St Catherine’s Park, which sits on the Lucan side of Leixlip, on the border between Co Kildare and Co Dublin.

But Boy B stuck to his story, offering alternate explanations to gardaí for the inconsistencies between the CCTV footage and his account.

The first change to his story came the next morning, at the start of interview four. The boy had spent the night in an office on the second floor of the station. Because the Children Act forbids child suspects from being detained in cells, gardaí had cleared an office for the boy and brought in bedding so he and his mother could sleep there overnight. The station had been closed to all other prisoners to ensure the boy didn’t come into contact with any other adults.

His solicitor told the detectives the boy had reflected on his statement overnight and wanted to make a change. “I’m going to retell the story of what actually happened,” Boy B said. “What I told you yesterday was a lie.”

He went on to say he and Ana had met Boy A by the BMX track in the park, not by Courtyard Lane as he previously claimed. Despite the dramatic preamble, the boy’s admission of dishonesty did little to advance the case. He claimed he lied because he initially got confused about his movements in the park and felt he couldn’t change his story without arousing suspicion.

Until then Boy B had remained remarkably calm.

A highly intelligent child, he spoke calmly, clearly and in full sentences. When gardaí asked if he knew what words like “detention” or “murder” meant he gave concise, accurate answers. At one point Gannon asked if he knew what the word “arrest” meant. “That you are detaining me for something that I did or might have done,” Boy B replied.

He appeared to have a large vocabulary for his age (he described Ana as wearing “synthetic leather” trousers) and put his answers into context when they might otherwise have been confusing. He sounded more like a young adult at a job interview than a 13-year-old boy accused of murder.

In short, up to that point he appeared more than a match for the detectives’ gentle interview approach.

But, despite appearing relatively inconsequential, Boy B’s concession that he had told lies marked a turning point in the interviews and in the wider case.

It provided the detectives with a valuable tool. Because he had admitted to lying once, Daly and Gannon could cast doubt over everything else the boy had told them. Now, whenever the boy said anything that sounded fishy, they could remind him he had already lied to them and had been found out.

The Garda Síochána interview model was introduced following the Morris tribunal, which heavily criticised the informal and sometimes oppressive interview tactics employed by the force. The model introduced a standardised approach to interviews across the Garda. All operational members are now trained in eliciting information from victims, witnesses and suspects while being careful not to lead them into simply telling them what they want to hear.

After completing an intensive two-week course at the Garda College, in Templemore, Daly had qualified as a level-three interviewer, the second-highest in the four-tier training hierarchy.

Level-three interviewers usually focus on serious crimes such as murder and rape. They’re trained to prepare extensively for each interview. If a suspect has an excuse for their actions, it is vital the interviewer immediately be able to cite any evidence that might disprove it.

Although their approach seems natural and fluid, level-three interviewers are actually following a strict formula. The first step is to build rapport. This creates “a non-judgmental, non-coercive atmosphere conducive to disclosure”, according to a 2016 study of the model.

Daly spent large parts of the first interview asking Boy B about his interests and hobbies. He asked what video games he liked (Halo and Outlast) and about his favourite Marvel character (Deadpool). There was laughter as Daly told Boy B he’d have to spell the name of his favourite YouTube star, PewDiePie, for him.

“Any outdoor interests?” Daly asked. The boy said sometimes he and his friend used the pull-up bars in the park.

“Can you do a pull-up?” the detective asked.

“Yeah.”

“Good man.”

There was no problem with the boy taking breaks whenever he wanted, and there were several trips to the vending machine or shop to get him chewing gum or Ribena.

With the suspect put at ease, the next step, in line with Daly’s training, was to let the boy tell his story in his own words, without interruptions. Next he began to challenge the boy, gently at first, by highlighting the inconsistencies and improbabilities in his account.

“This is your opportunity,” Daly told him in a low voice. “Now is the time for the truth.”

Aside from boredom, and sometimes frustration, Boy B had so far displayed little emotion or distress. That changed as Daly and Gannon started to show him evidence from the abandoned house.

When Daly showed him a photograph of the crime scene with Ana’s body pixelated out, Boy B held his head in his hands and responded: “Jesus, one of my closest friends.” He quickly added he was referring to Boy A, not Ana.

“Wait a minute. Holy shit. Oh my God,” he said when shown a photograph of the insulation tape that had been wrapped around Ana’s neck. He told gardaí he had recently given the tape to Boy A.

Over the years detectives tend to pick up their own techniques for interviewing dishonest suspects. Some will pause suddenly at crucial moments, catching the suspect by surprise and throwing them off guard. Others like to refuse requests for a cigarette or glass of water until the suspect gives them new information. In some cases it makes sense to appeal to a suspect’s conscience. In others, vague insinuations about lengthy prison sentences are more effective.

In this case the boy’s age meant Daly was highly constrained, and had to be particularly careful not to use any tactics that a court might later view as oppressive or intimidating.

But, although it remained gentler than most murder interviews, by the fifth session the atmosphere in the room had changed drastically. Frustration was starting to creep into Daly’s voice; his tone suggested he was getting tired of the boy’s lies.

He never lost his temper, however. Instead he continued to urge the boy to come clean: “You owe it to everyone to start telling the truth here. You owe it to your mam, to yourself, to tell the truth, because unfortunately a girl has been brutally murdered.”

Although he had changed several important aspects of his story by that point, Boy B continued to deny any knowledge of what happened to Ana in the abandoned house.

The most important breakthrough came in the late afternoon of May 25th, about halfway through interview five. Daly had just informed the boy that they had a witness who saw a teenager they believed to be him walking through a field and towards the abandoned house. The boy admitted to going into the field to look around but insisted he went no farther.

Daly sighed. “You’re making this up as you go along, [Boy B,] I have to say. I’m presenting facts and evidence to you, and you’re changing your story to suit. You can’t keep doing this.”

There was a long pause before Boy B asked his mother to leave the room. Daly said this was not possible, as he was a minor and required a guardian at all times. His solicitor suggested they take a break, but Daly wanted to keep going. “I think we’re at a crucial point here. The truth, that’s all we want.”

Boy B took a deep breath before telling gardaí that Boy A went into the house with Ana. “I left, and that’s when I heard the scream, and then I ran,” he said. “It was a really strong scream. I knew that it was Ana, but since [Boy A] was there she’d be fine. He’d protect her. The scream was, like, really loud. Just before it ended it got muffled, like someone covered her mouth.”

After dozens of lies the boy had admitted for the first time to knowing something had happened to Ana. He started to weep, as did his mother. When the moment was played back in court, exactly a year later, Ana’s mother, Geraldine, would also weep. Much worse was to come.

Ana’s last day

Ana wasn’t very good at geography. One of the several ailments afflicting the young girl was a short-term memory problem, which made it difficult for her to recall all the terms she needed. In general Ana wasn’t academically inclined, her mother later said. Part of this was down to her having been adopted from Russia at the age of two, leaving her playing catch-up with her peers in English-language skills. Problems with her hearing compounded the issue.

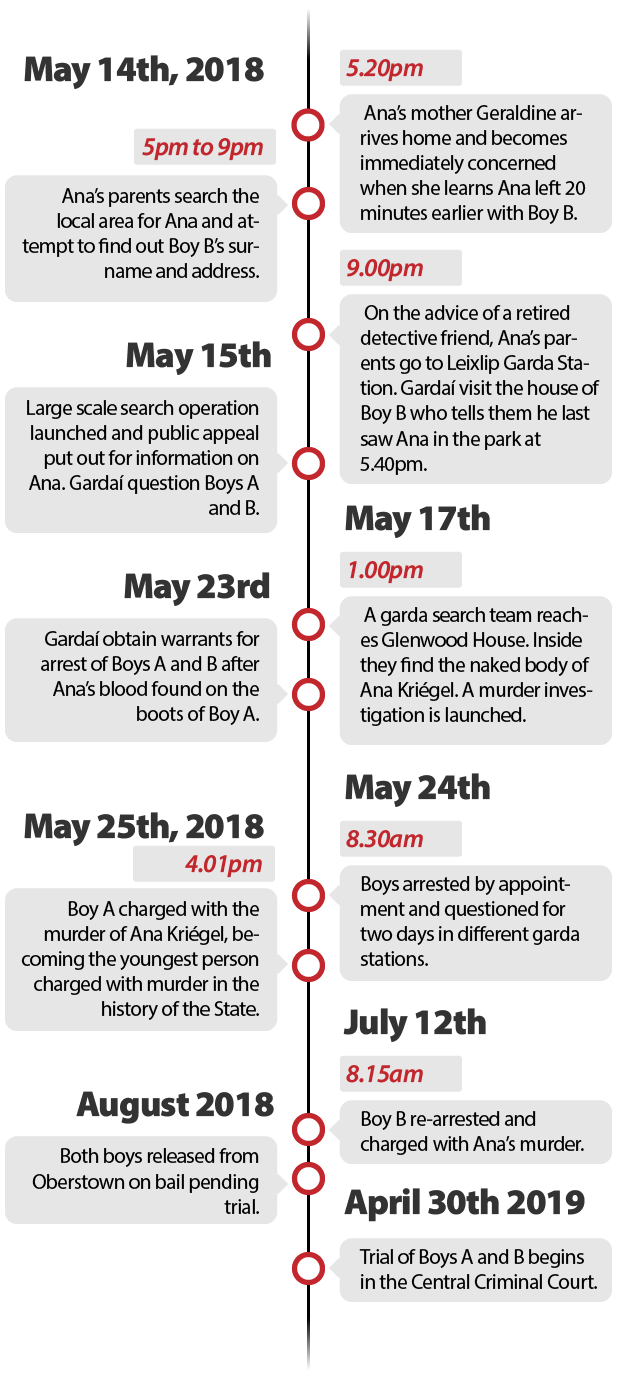

There were exams the following week, so on the morning of Sunday, May 13th, 2018, Geraldine Kriégel planned to sit down with her daughter to help her study.

“No, Mam, you must be exhausted. We can do it later,” Ana told her mother. Geraldine agreed. There was to be a small family gathering later, but now they had a few hours to relax beforehand.

In the meantime Ana did one of her favourite things: watching movies with her mother and eating popcorn.

Later Geraldine ordered pizza for the party. Ana didn’t like pizza, so she walked into Leixlip and brought home a spice bag from a Chinese takeaway. Back at the house the children played while the adults had a drink in the conservatory.

At one stage Ana and her cousin went up to her room to make a YouTube video, another of her favourite hobbies. Like nearly every other teenager, Ana used a staggering number of social-media apps, including Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat and Houseparty. Her favourite was YouTube.

She would make videos about dancing, clothes and make-up for her 100 or so subscribers. Although the videos attracted many pleasant comments, they also brought poisonous barbs and even threats. One viewer told Ana to “go die”. Another said they would have her executed.

A short time later the family gathering ended; there was school the next day. Ana’s cousins were collected, and she went to bed at about 10.30pm.

Before going to sleep Ana asked her mother to wake her the next morning in time to say goodbye before she left for work. Like most teenagers, Ana liked to sleep in, but she had promised her parents she would try to get up earlier in the morning.

Geraldine Kriégel is a senior manager in the legal department of CIÉ, the State public-transport company. She was usually first up in the morning; her husband, Patric Kriégel, had retired from teaching French at Dublin Institute of Technology.

That morning Ana reminded her mother that she needed a note to get out of school at 2.30pm; she had a counselling appointment with Kildare Youth Services, which she attended once a week. Geraldine wrote the note, kissed Ana goodbye and left to get the train to Dublin, where she had a meeting.

Her daughter put on her school uniform, had a little breakfast and left sometime later.

The plan was for Ana to eat lunch at school before walking to counselling. But she decided to return home to eat before going to her appointment.

After counselling she came home, had a snack of some oven chips and went to her room. It was around this time she tried to phone her mother. The two frequently called or texted each other during the day. When Ana rang at 4.02pm, Geraldine was in a meeting and couldn’t answer. She texted her daughter to tell her she’d call shortly.

Patric was relaxing outside, taking in the May sunshine, when, at 4.55pm, he heard the doorbell. It was Boy B. He asked for Ana. When her father told her who was at the door, Ana was confused. She knew who the boy was, but they were by no means friends. Nonetheless she went down and spoke to him.

Patric saw Ana standing in the doorway, whispering to the boy. He didn’t find this unusual, he would later recall. “I think a lot of teens do it.”

She then ran back upstairs to get her hoody before telling Patric she was going out. Ana’s mother had bought the hoody for her online, from China. It was distinctive: black with writing down the sleeves. Within days most of Ireland would see photographs in newspapers and on television of Ana wearing it.

Patric reminded Ana about her exams and told her she was supposed to study that evening. Ana responded that nobody had told her this and that she wouldn’t be long.

“I believe she meant it. I knew from the way she was saying it that she meant exactly that,” Patric would later say.

Seconds after Ana left, Patric realised he had forgotten to ask where she was going. He went to the door and saw Ana walking towards St Catherine’s Park. The boy, who was carrying a small backpack, walked ahead of her. The two didn’t appear to be talking.

Although it was unusual for this boy to call for Ana, Patric was not overly concerned. “She was happy when she left. She gave me a big smile.”

Geraldine was on the train home at the time. She had been chatting to a friend who got off at Coolmine, in north Dublin, about 10 minutes before Geraldine’s stop, at about 5.10pm, finally giving her a chance to return Ana’s call from earlier. It went to voicemail. Geraldine didn’t leave a message, as she knew she would see Ana when she got home.

Normally she wouldn’t get home so early, but that day she had taken the train because of her meeting in Dublin. She found her husband in the back garden. He told her Ana had gone out with Boy B. “I became immediately concerned, because he has nothing to do with her,” Geraldine recalled later. “Nobody calls for Ana.”

‘Endlessly bullied’

To understand why Geraldine Kriégel was so concerned when she learned Ana had left the house with Boy B, it’s necessary to understand recent events in the teenager’s life.

Ana was savagely bullied inside and outside school. Above all she wanted friends her own age, friends who weren’t her cousins. But she had few.

Born in February 2004 in Novokuznetsk, an industrial city in western Siberia, Ana was adopted and brought to Ireland by Geraldine and Patric in 2006. She was their first child.

Despite having no link to Russia themselves, Ana’s parents made sure she retained some connection to her native culture. They kept her name, Anastasia, although everyone would shorten it to Ana. On the day she died her social-media profile picture was a Siberian wolf.

For most of primary school Ana was a happy pupil despite struggling with a variety of health issues.

Photograph: Alan Betson/The Irish Times

Doctors found a tumour in her right ear that required a 5½-hour operation to remove. She could barely hear from that ear afterwards and would always walk or stand on people’s left side as a result. She had poor eyesight and a scar on the back of her head from the surgery, along with another on her chin from a time when she fell as a young child.

As she entered her teens she also suffered from a painful condition, sometimes seen in adolescents, that occurs when the bones grow faster than the muscles.

Emotional problems began to appear as primary school came to an end. On one occasion her parents were alerted that Ana had told a teacher she was feeling suicidal.

She was excited about going to secondary school, but her parents and teachers were worried. Ana’s resource teacher told Geraldine and Patric she was terrified for her, because she was so innocent. She feared other students would take advantage of this.

The parents met early with the management of the secondary school to highlight their concerns about Ana being a potential target for bullies.

In fact, the bullies didn’t even wait for her to start school. During the summer after sixth class Ana was bullied online by third-year students who sent her sexually suggestive messages.

Much of the bullying was about her height. Ana was “a typical Siberian”, her mother would later say in court, strong and tall. By the time she was 13 she was 173cm, or 5ft 8in, tall. “She looked much older than her years,” her mother said. “She could have passed for an 18-year-old.”

“She was taller than me,” Patric recalled with a smile.

The bullies also mocked the fact that she was adopted, telling her she had a “fake mam and dad”. Geraldine and Patric took screenshots of some of the messages and showed them to the school.

But the situation did not improve after she started secondary school. “She was endlessly bullied,” Geraldine said.

That Halloween Ana came home hysterical and terrified. She had been walking back after supervising a disco for young children (“she volunteered for everything,” Geraldine said) when four boys approached. One asked her repeatedly for sex before hitting her on the backside. A complaint was made to the Garda, and the boy received a caution.

Ana would walk for hours at a time, usually while listening to music on her distinctive blue headphones. She almost always walked alone. “You would see other girls walking in groups, and Ana would be walking alone,” Geraldine would tell the court.

Her parents painted a picture of a kind-hearted, innocent girl who craved friendship. She loved spending time at home with her family but longed for someone her own age to hang around with.

“People didn’t understand her. She was unique and full of fun,” Patric said. “She couldn’t hate anyone even though some of the people were bullying her. She was disappointed with people. That happened quite regularly. She tried to make friends but might say the wrong thing. She was a teenager.”

He said Ana started to act out in worrying ways. There were fights at school, one of which resulted in a suspension. One day she painted a black eye on herself before going into school.

“It was attention seeking. For me it was an expression of pain she suffered on the inside,” Geraldine said.

“She said she felt invisible,” said Patric.

At one point it was discovered that Ana had set up fake social-media accounts that she was using to send bullying messages to herself. From then on she had to give all the passwords to her apps to Geraldine, who would check her phone every night.

“She didn’t like it, but she knew if she didn’t I would take the phone,” her mother said. Shortly before Ana’s death Geraldine found a photograph on the phone of her blindfolded and tied to a chair. Ana told her mother it was part of a prank. She and another girl were pretending she was in trouble, to see if another boy would come and rescue her.

As Ana’s emotional problems grew, her parents felt she needed some outside support. They approached Kildare Youth Services, which initially said it couldn’t see Ana, because she had self-harmed. Ana had recently cut her arm with a scissors; her parents believed she did it in imitation of a boy she knew.

She was referred to Pieta House, the charity that helps people who self-harm or are in suicidal distress, where she did well. Staff there judged her as being at a very low risk of suicide. They had to ring Patric and get him to pick her up from the sessions, as the prospect of being bullied made her scared to walk home alone.

After six sessions at Pieta House she was accepted by Kildare Youth Services, the volunteer-supported organisation she was attending at the time of her murder.

Ana did have a handful of friends, including a girl who would call over for sleepovers and to watch films. But she was certainly not friends with Boy B, something Geraldine was well aware of when she returned home on Monday, May 14th.

The search

Shortly after 5.30pm Geraldine texted her daughter a two-word message: “Home now”. There was no response. She talked it over with Patric before sending another message a few minutes later: “Answer me now or I’m calling the police.” The part about the police was just to get Ana’s attention, Geraldine later explained.

She was conflicted. She knew Ana had only been gone for half an hour, and felt like a “paranoid mother”, but she was extremely worried.

Geraldine walked to the park. She could see children playing and adults walking their dogs, but she saw no sign of Ana.

After dinner she went out looking for her in the car, driving around local estates. Ana loved to go for long walks, so she could have been anywhere in the area.

Once she got home, Geraldine and Patric went on Facebook to find out Boy B’s surname. They knew him vaguely but had no idea where he lived or who his parents were. Geraldine rang around, trying to find out his address, but without success.

She and Patric went to the house of John Cribbin, a friend who is a retired detective, for advice. He told them to go straight to the Garda. At that point Ana had been gone for four hours.

The parents went to Leixlip Garda station, where Geraldine explained it was highly unusual for Ana not to get in touch. She told gardaí her daughter was a communicator. “She would always respond. Even if she said she was not talking to you she would respond, to tell you she wasn’t talking to you.” Ana’s Irish and Russian passports were still at home, and she hadn’t eaten since lunch, Geraldine added.

Gardaí took her seriously, but there was no reason to be immediately concerned. Every week the Garda receives dozens of reports of missing children; the vast majority turn up within a few hours.

The first job for gardaí was to visit the house of Boy B after locating his address on their Pulse computer system.

Garda Conor Muldoon went to the house that evening. Boy B told him that he had called for Ana that day, that they had walked in the park and that he had left her company there at 5.40pm. It was the first of dozens of lies he would tell investigators.

The next day Ana’s family got up early to resume the search. Joined by friends and family, they walked the local area and spoke to anyone they could think of who might know where Ana was. By now gardaí were also worried, and a missing-person investigation began in earnest. Sgt John Dunne was tasked with returning to Boy B’s house to question him further. This time Boy B told the garda he had called for Ana the previous day on behalf of his friend Boy A.

Ana had a crush on Boy A, but he wasn’t interested, and he wanted to meet up with her to tell her, Boy B said. He said he brought Ana to the park, where she met Boy A, before leaving them and returning to his house to do his homework.

Dunne brought Boy B to the park, so the teenager could show him exactly where he went with Ana. Boy B showed the garda where they had entered the park, where they had met Boy A and where he had left the two of them to talk. The garda marked all of these locations using the GPS function on his Tetra radio before dropping the boy home.

Meanwhile a Garda family-liaison officer was appointed to keep Ana’s family informed about the search. Standard procedure at this stage was to issue a media appeal. Ana’s parents provided some photographs of their daughter, including one of her wearing the distinctive black-and-white hoody.

It was in the late afternoon of Tuesday, May 15th, when the wider public first learned Ana Kriégel’s name.

“Gardaí are seeking the public’s help in tracing 14-year-old Anastasia Kriegel, who was last seen at her home in Leixlip, Co Kildare, at 5pm on Monday the 14th of May 2018,” the press release said. “Anastasia is described as 5’8”, black shoulder length hair, sallow skin and slim build.”

The Garda sends out missing-person alerts almost daily. The week before Ana’s death it issued three, all relating to teenagers. All three of those young people were later found safe and well.

After the appeal about Ana went out potential leads began to pour in, all of which the Garda had to follow up.

One caller said he had seen her in Dundrum, in south Dublin. Another told gardaí they had seen her in the departure area of Dublin Airport. One of the more promising leads came from a local woman who said her daughter had seen Ana on the morning of May 15th by a nearby cul-de-sac. Gardaí followed up and discovered that a school friend lived on the cul-de-sac and that he hadn’t attended school that day. But a search of the boy’s house revealed nothing, and the lead turned out to be a dead end.

Back in Lucan, Dunne and his colleagues continued to comb the area. After walking the park with Boy B the garda decided to search the railway line, but he found nothing. As Dunne was walking back he was stopped by a man and his son. The man had heard about Ana going missing and suggested the garda check the back of the local sewage-treatment plant, as teenagers tended to hang around there.

It was only later that day Dunne realised this man was Boy A’s father and the teen with him was Boy A.

At that stage both boys were being treated as witnesses, not suspects. Gardaí had no reason to believe they had hurt Ana or even that Ana had been hurt at all. But, because they were the last ones to have seen her, any information they could provide was vital.

On Tuesday afternoon a decision was taken to bring Boy B back to the park, this time with Boy A.

The boys led the way as Dunne and Sgt Aonghus Hussey followed with Boy A’s father. As they walked Dunne noticed Boy B was leading them on a different route from one he showed them earlier.

The boys came to a stop on a path near the BMX track in the park. Dunne and Hussey both saw them exchange what they would later describe as a glance or look. It was the first indication the boys weren’t telling the Garda everything. It was decided formal statements should be taken, so they could clarify their exact movements.

Both boys were taken to Lucan Garda station with their parents.

Boy B told gardaí the same story he gave earlier. “I have no clue what happened to her,” he said, adding that the first time he heard something was wrong was when gardaí called to his door the night before.

Boy A gave a detailed statement about his movements. He said Boy B was one of his best friends and had called to his house after school. Boy A was doing his chores, so they arranged to meet in the park in a while. When Boy B arrived there he was with Ana, a girl he knew from school, but “not that well”.

He told gardaí: “At one stage Ana said to me, ‘I have something to ask you. I was wondering if you wanted to go out with me.’ I was surprised. It came out of nowhere. I kind of knew she liked me, because she kind of asked me out [before].”

He said he wanted to tell her “gently” that he didn’t want to go out with her. “I said, ‘I’m sorry, but I’m not interested’. She didn’t answer. She said nothing. She walked off. She looked annoyed and sad at the same time.”

By this stage Boy B had also left, Boy A said. He walked on alone until he was attacked by “two males”. One grabbed him by the shoulder and pulled him to the ground; then both started kicking him, he claimed.

The attack ended when Boy A “got up and kicked one of them in the head”, causing both to flee. Gardaí were somewhat sceptical of the story. The boy did have injuries consistent with an assault – his arm and leg were injured, and his face was cut – but his account didn’t feel right.

In particular, his description of defeating his attacker with a kick to the head sounded more like teenage fantasy than reality.

Nevertheless gardaí were assigned to investigate the alleged assault. Boy A was taken to Garda headquarters, in Phoenix Park in Dublin, where he helped investigators compile a photofit of the attackers. None of the witnesses in the park that day saw anybody matching the photofit. CCTV cameras also failed to pick up anyone matching the description.

The following day, Wednesday, May 16th, the search was kicked up a gear. There were now serious concerns that Ana may have been harmed or even killed.

Insp Mark O’Neill of Lucan Garda station was assigned to lead the missing-person investigation, and all members coming on duty in stations in north Dublin and Kildare were briefed. Specialist search teams were brought in, including the Garda subaqua unit, which searched the River Liffey and other bodies of water in the area. The Civil Defence provided 60 members to aid in the operation. The Garda crime and security branch was asked to analyse mobile-phone traffic, to try to track Ana’s movements.

A mannequin or ‘something terrible’

Her body was found in an abandoned farmhouse on May 17th, 2018.

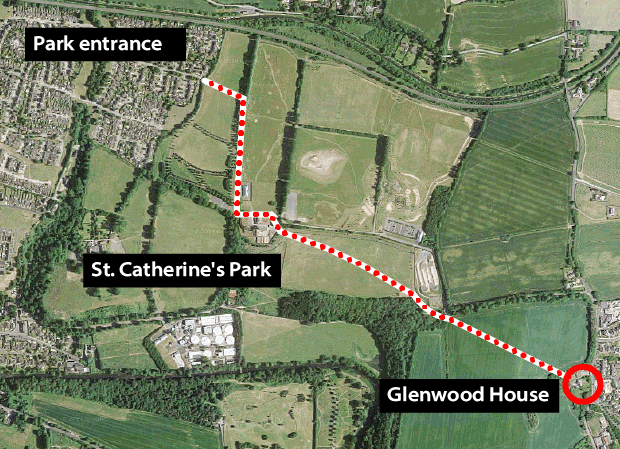

Glenwood House was built around 1800; some say it was designed by James Gandon, the architect of the Custom House and the Four Courts, on the Liffey in Dublin. The handsome farmhouse sits on just over 40 hectares, or 100 acres, of farmland at the edge of St Catherine’s Park, on the Lucan-Clonee road, in an area known locally as Coldblow.

It was home to the Colgan family until the last decades of the 20th century, before being abandoned entirely.

The subsequent years were not kind to Glenwood. Despite being a protected structure because of its architectural significance, the house was effectively a ruin by May 2018. Bottles and cans littered the floors, the result of the house’s popularity with local teenagers looking to avoid the prying eyes of parents and gardaí. The roof had collapsed in several places, and several rooms had been gutted by fire.

The house continued its decline even after it was bought, in the early 2000s, by a company linked to the hotelier Noel O’Callaghan, for €10.5 million. In recent years the company has been trying to get planning permission to turn it into a 62-bed nursing home, a plan welcomed by most locals, who despaired that the once-fine structure had become an eyesore.*

One group, Old Lucan, appealed to locals in January 2018 to contact Fingal County Council and ask it to enforce the building’s protected-structure status. There has been no update on the campaign or the owner’s attempts to repurpose Glenwood since April 2018.

“We all know what happened there,” one member of the Old Lucan group wrote on its Facebook page recently. “Once the trial is over it should be knocked down and so should the adjacent buildings.”

On the morning of Thursday, May 17th, 2018, Sgt Declan Birchall and his specially trained four-person search team were deployed to an area of Lucan that included part of St Catherine’s Park and Glenwood House.

Working from maps, and using a grid system, the team methodically searched the park, including all its hedgerows and ditches. Once they got to the large field beside the park they used slash hooks to clear the way.

Glenwood House stood at the end of the field. Birchall, like most local gardaí, was familiar with the building, having responded to reports of teenagers messing there over the years.

Birchall searched the outbuildings while his colleague Garda Sean White went into the main house through the rear porch. At the end of one of the corridors, at the front of the house, White looked into what would later be designated as Room 1.

It was dark inside. The windows were boarded up, and the only light came from a hole in one of the planks over the glass. In the gloom White thought he could make out a figure. He could definitely smell dried blood. The garda would later tell a colleague he believed he was looking at either a mannequin “or something terrible”.

He called out but got no response. In line with his training, he stepped into the room to confirm what he thought he had seen, then left and called for assistance.

Birchall rushed into the house when he heard White shout “Find”, to indicate he had located something of significance.

As the search team leader he entered Room 1 to confirm what White believed he had seen. Inside was Ana Kriégel’s body, naked except for her black socks.

At first Birchall believed something was covering Ana’s face. When he leaned closer he realised it was her hair, which he said was stuck to her face as if she had been “thrashing” it around.

Her clothing and pieces of her iPhone were scattered around the room. Nearby were a cement block and a large stick, both of which were bloodstained. There was also blood staining on the walls and on the carpeted floor. The blood had clearly come from the many wounds on the girl’s body.

A long length of Tescon insulation tape was partially wrapped around her neck. She had three fingers inside the tape, as if she was trying to get it off.

Gardaí quickly established a crime scene while they awaited the arrival of Supt John Gordon, from Lucan Garda station. A local GP was called to formally pronounce death, and within an hour the Kriégel family had been told by their Garda liaison officer that Ana’s body had been found. They were told they would have to go to the morgue that evening, to make a formal identification.

The missing-person investigation immediately became a murder investigation, and Insp O’Neill was appointed senior investigating officer, with 20 gardaí working under him. For now his job would be to marshal the many forensic and technical experts who would file in and out of Glenwood House for the next several days.

Every inch of Room 1 would be examined and catalogued, along with every beer can, cigarette butt and piece of debris it contained.

The most pressing task was the pathology exam. The State pathologist, Prof Marie Cassidy (she has since retired), visited the location before overseeing the transport of the body by hearse to the State Laboratory, in Whitehall in north Dublin, for a full autopsy that evening.

Ana had a staggering number of injuries. During the trial Cassidy would spend about 40 minutes just listing the 50 injury sites. There were bruises and lacerations all over the body, the most serious to Ana’s head, face and neck.

Cassidy concluded Ana had died from blunt-force trauma to the head and neck. There were also signs of compression to her neck, but there was no evidence the tape had caused this.

Other injuries suggested there had been penetration, or attempted penetration, of the vagina with something, but Cassidy could not determine what that something was. She also couldn’t tell if Ana had been conscious at the time.

On the basis of the pathology and forensic evidence, the Garda suspected Ana had been beaten to the ground with a heavy stick shortly after entering the room, then hit four times with a heavy object such as a concrete block.

Next she was pulled towards the window, where there was more light. It was likely here she was sexually assaulted. Her false nails scattered around the room indicated she had fought her attacker fiercely.

Despite the huge amount of forensic material at the scene nothing immediately pointed towards a suspect. All the fingerprints and blood belonged to Ana. But scientists from Forensic Science Ireland made a grim breakthrough when they examined Ana’s top and discovered semen stains.

The focus of the investigation immediately returned to the two boys. The discrepancies in their accounts meant gardaí already had enough reason to suspect them, but they wanted to wait for forensic proof that at least one of them was at the scene. That came a few days later, when Forensic Science Ireland reported that Ana’s blood was found on Boy A’s boots, which had already been taken by gardaí investigating the allegation that he had been assaulted by two men in the park.

As part of the assault investigation gardaí had also taken the boy’s phone. On it they found more cause to suspect he was behind Ana’s death. The phone contained a screenshot of a list of Youtube videos, including “The 15 most gruesome torture methods in history”, “Horror films that will blow everything away” and “Until Dawn – Get Jessica’s clothes off”; Until Dawn seemed to be a reference to a popular horror video game. There was also a result for Jeff the Killer, a widely shared short story about a teenager who murders his family.

On their own these results could have been interpreted as reflecting the macabre but not entirely unexpected interests of a young teenage boy. But for gardaí the presence of another search result, for “abandoned places in Lucan”, put things in a different light.

Arrest, interview and charge

A week after Ana’s body was found gardaí were granted a warrant to arrest both boys.

From the very beginning of the investigation concessions were made for their age; some were required by law, others were at the discretion of the Garda, lawyers and judges.

Both boys’ parents were informed on the evening of May 23rd their sons would be arrested the following day. The parents were asked to bring them to the Garda station in the morning. But they were not told their homes would be searched immediately after the arrests.

Insp O’Neill told his team they were to carry these out with the utmost discretion. Gardaí used rental cars instead of patrol cars to get there. They wore plain clothes and put their evidence bags in black sacks before they were taken out of the houses.

After he was arrested Boy A was interviewed at Clondalkin Garda station, in west Dublin, in the company of his father and their solicitor Donough Molloy. As they had done with Boy B, gardaí started by asking him if he knew the difference between right and wrong.

“Leaving the door open for somebody” is right; “tripping somebody up” or stealing a chocolate bar is wrong, Boy A told Det Gardaí Marcus Roantree and Tomas Doyle.

He explained the difference between truth and lies by saying: “Truth is if you tell somebody what happened. A lie is if you don’t tell somebody what happened.”

Asked about his interests, Boy A said he liked “anatomy, the human body” and “inner life, the skeleton”. He said he liked anatomical drawing. The detectives asked if he liked drawing live people. “No, more evolutionary”, he responded.

During interview two Boy A gave gardaí much the same story they had heard from Boy B, that he had met Ana in the park that day but was not with her in the lead-up to the time she was reported missing.

When he was shown CCTV footage, he said at one point that two people caught on camera could have been the ones who beat him up. “That might be good news,” he said. “Is there any more footage?” Those figures were actually Boy B and Ana.

Det Garda Doyle then told the boy that Ana’s blood was found on his boots. “Are you joking me?” Boy A asked. “You can’t be serious.”

The interview paused after Boy A asked for some air. His solicitor asked if he was going to be sick, and one of the gardaí got him a glass of water.

When questioning resumed Doyle said: “What I’m saying to you is the only place you could have got the blood on your boots was in that room, so were you in that room?” “No,” he replied.

The detectives showed Boy A a photograph of the tape around Ana’s neck. Boy A said he had never had any tape like that.

Asked about the search results on his phone, Boy A said the torture-methods result came up when he was searching for horror films online. He said he wasn’t interested in torture films.

Despite being presented with strong forensic evidence, Boy A did not admit any involvement in the murder. Most of his responses were of the “no comment” or “I don’t know” type.

Detectives were disappointed. The forensics were strong, but without admissions Boy A might be able to claim that he acted in self-defence or that he never meant to kill Ana.

Nine kilometres away in Finglas the interviews with Boy B were going much better for gardaí. After eventually telling them during his fifth interview that he heard Ana scream, the boy gradually admitted more and more.

This culminated in Boy B telling Daly and Gannon that Ana had gone into Room 1 with Boy A. Despite being told to leave by Boy A, Boy B decided to explore the rest of the house. Then the sound of “shuffling” made him run to Room 1, where he saw Boy A “kind of flip” Ana. He described a judo-type move to the detectives.

Boy A started to choke her and pull off her clothes, he said. Ana was crying and saying: “No, no. Don’t do this.”

He said at this point both Boy A and Ana turned to look at him in the doorway, which made him run away. Boy A had a “blank look on his face”, he said.

It still wasn’t the truth, but it was as close as the detectives could get in the limited time for which they could detain Boy B.

The detectives, who were being advised by a specialist from the Garda national bureau of criminal investigation, wondered if Boy B’s account could be used to get Boy A talking over in Clondalkin. Perhaps Boy A would realise all the blame was being put on him and want to defend himself.

A few of the most relevant pages of Boy B’s fifth interview were copied and printed before being sent across town to Roantree and Doyle.

In their sixth and final interview, the detectives read the pages to Boy A before asking if there was anything he wanted to add.

“[Boy B] is lying. That is all,” the boy replied.

On the afternoon of Thursday, May 25th, 10 days after Ana’s murder, an official from the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions called Insp O’Neill and gave permission for Boy A to be charged with murder.

The charge was put to him at 4.01pm at Clondalkin Garda station, just before the 24-hour limit for questioning expired. Neither he nor his father, who was also present, made any reply.

An hour later he was brought in a Garda van, in the company of his parents, to the Children Court, in Smithfield in Dublin, his first court appearance of many.

Gardaí normally announce arrests in murder investigations shortly after they occur, particularly in high-profile cases. But here they made an exception. The arrest of the boys was not made public until just before Boy A was due in court. At the time gardaí said they were concerned about vigilante behaviour against the boys’ families. Local gardaí would later mount discreet extra patrols to ensure the families’ safety.

The Children Court is a bleak grey-and-brown stone building on the corner of Smithfield Square. Inside and up the stairs are two cramped courtrooms, although usually only one is in use. Every day a stream of children pass through the court, usually on relatively minor charges to do with public order, drug possession and theft.

Jail terms are rare, and the vast majority of defendants enter early guilty pleas. The Children Court is effectively a District Court, the lowest tier of the criminal-justice system. As at a District Court, there is no jury, and a judge may impose a maximum 12-month sentence for any one offence.

So Boy A’s case was never going to stay there. The legislation requires Children Court judges to transfer murder and rape cases to the Central Criminal Court, where children accused of such crimes are effectively tried as adults. A full jury hears the case, and the judge has a much wider array of sentencing powers.

Fifteen minutes after the Garda van arrived at Smithfield, Boy A appeared in the courtroom with his parents. Also packed into the room were two solicitors, two detectives, three journalists and Judge John O’Connor.

The judge told the boy’s mother she could sit beside him if she wished. His grandfather entered a short time later and was granted permission to stay.

Asked by Judge O’Connor if it was his first time in court, the boy replied “yes”.

At that early stage the priority for the boy’s family was getting bail. Oberstown Children Detention Campus, in Lusk in north Co Dublin, is the only facility in the State for holding underage detainees. It is not a particularly pleasant place for anyone, but a sheltered 13-year-old with no criminal record was likely to find it especially tough.

As a District Court judge, O’Connor had no power to grant bail in murder cases. The boy would have to apply to the High Court at a later date. The judge remanded Boy A to Oberstown, allowing him a few moments with his parents before departing. The boy looked confused as he was ushered out of the courtroom. He walked with a pronounced limp.

The evidence against Boy A accumulated quickly once he was charged. During the search of his house gardaí found a backpack in his bedroom containing gloves, knee pads, shinguards, a scarf-like “snood” and a home-made mask. This would soon become known among investigators as the “murder kit”.

The skull-like mask would become one of the most striking pieces of evidence in the case. Skin coloured, it covered only the top half of the face. Eye and nose holes had been cut out, and sharp teeth had been cut into the upper jaw and painted red. Ana’s blood was found on the inside and outside of the mask, as well as on the knee pads, gloves and backpack.

The gloves were particularly important to the Garda case, as they explained why no fingerprints were found at the scene.

An examination of two phones found in Boy A’s bedroom revealed almost 12,500 images, the vast majority of which were pornographic. One featured a man in a balaclava looking at a semi-naked woman; another showed a man choke a woman as a second man watched.

The phones’ memories showed several pornographic videos had been accessed online, including one with a title referring to a woman called Anastasia. Another referred to Russian teens.

Perhaps even more concerning was evidence of searches for “child porn”, “horse porn” and “dead boy prank in abandoned haunted school”. When the trial started, the following year, none of these details would be heard by the jury.

Gardaí also found witnesses to bolster their case against Boy A. A dog walker had said he saw a boy roughly matching his description “making a beeline” for the abandoned house on May 14th. A school friend told them Boy A appeared agitated and fidgety in the days after Ana went missing.

When the analysis of the semen on Ana’s top showed it matched Boy A’s DNA, the Garda got permission to charge him with aggravated sexual assault; the aggravated part referred to the extreme violence involved. The new evidence also allowed them to rearrest Boy B for further questioning.

Boy B was arrested again by appointment on July 8th and brought to Lucan Garda station, where he was interviewed another three times by Daly and Gannon. Daly went through the same procedure as before, gently coaxing the boy to reveal more about what happened that day.

This time Boy B said his coaccused wore the mask, which he described as a zombie mask, when he attacked Ana. He described it as a “really cool” mask that Boy A had made the previous Halloween.

Boy B gave gardaí some more details about what he did and saw, including that he had entered the house alone first and picked up a stick there. But he continued to deny any involvement in the attack.

He also told gardaí of a conversation he had with Boy A the month before Ana’s murder. He described the conversation as going like this:

Boy A: “Hey, want to kill somebody?”

Boy B: “No”.

Boy A: “Ah here, why not?”

Boy B: “Because it’s retarded.”

Boy A: “Oh, come on.”

Boy B: “Who are you planning on killing?”

Boy A: “Ana Kriégel”.

Boy B: “In your dreams”.

Boy B said he presumed that his friend was messing and that he always said things like that. He repeated that he had no idea what his friend was planning on May 14th.

“Why didn’t you do anything in the room?” Daly asked.

“Because I was scared. I was shocked. I didn’t know what to do, because my brain was frozen, frozen in place. I didn’t know what to do.”

He lied to gardaí the day after Ana went missing because he was “just trying to forget about it and pretend nothing happened”.

“Did you not think you owed it to Ana and her family?” Daly asked.

The boy replied he was scared of being framed by Boy A.

He said he was ashamed of not helping Ana that day.

“But you could have saved her,” the detective said.

“I know.”

“Why didn’t you try and save her?”

“I don’t know.”

Daly accused the boy of telling “lie after lie after lie”, telling him: “You go and collect a girl that [Boy A] wants to kill, and you bring her to an abandoned house and you, in your words, ‘hand over’ that girl to [Boy A], the girl he said he wanted to kill.

“And then you were deceptive afterwards. You lie to everybody. Lie, lie, lie. You’re in a corner and you try to wriggle out of it by telling a story to suit. Do you see how this looks for you?”

Boy B said that he did. Det Garda Daly put it to Boy B that he let “a charade” play out in the days after Ana went missing, as people searched for her while he knew she was in the abandoned house.

“I didn’t know he would murder her,” Boy B said. “I kept thinking to myself, This isn’t real, this isn’t happening. I kept thinking, Boy A wouldn’t do this, it’s not like him.”

The detectives suspected that Boy B still wasn’t telling the whole truth, but they had to either charge or release him. He was released while the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions considered the matter. Four days later Boy B was rearrested and charged with Ana’s murder. He made no reply.

Bail

In the Children Court that day he addressed the hearing twice, once to confirm he had never been in court before and once to ask if he could go to the bathroom. Like his coaccused, he would have to apply to the High Court for bail.

Proceedings moved remarkably quickly once the accused were charged. There is usually a delay of between 18 and 24 months between the point of charge and the beginning of a murder trial. Legal issues can mean it takes much longer.

The speed in this case was almost unheard of, especially for a trial involving a long list of witnesses and a huge amount of forensic and CCTV evidence. In the back offices of Garda stations orders came down that work on the Kriégel case was to be prioritised. Analysis took days rather than weeks, and restrictions on overtime were eased. Forensic Science Ireland staff came in on evenings and at weekends to work on the case.

Later the Central Criminal Court would be asked to clear a non-negotiable four weeks for the trial in the first half of 2019.

Part of the reason for the speed of proceedings is that, at first, it looked as if the accused might not be granted bail before the trial. The authorities did not want to keep such young children, who like everybody else enjoyed the presumption of innocence, locked up for longer than necessary.

Boy A would spend more than two months in custody before being granted bail, in the High Court, on August 2nd.

The social-justice charity Extern, which the courts often use in complex cases, was asked to support and supervise the boy, to ensure he complied with the bail conditions.

Boy B spent just over a month in custody before being granted bail, on August 21st.

Both children would be free, albeit heavily supervised, until the start of their trial, in April this year.

Trial preparations

The legal age of criminal responsibility in Ireland is 12, but this drops to 10 when rape or murder is alleged. At 13, Boys A and B became the youngest people in the history of the State to be charged with murder.

Planning for the trial began at an early stage, with Mr Justice Paul McDermott assigned to hear it. Brendan Grehan SC, a criminal barrister with huge experience in high-profile trials such as those of the former Anglo Irish Bank chief executive David Drumm and the serial killer Mark Nash, would lead the case for the State.

The judge and barristers would wear neither wigs nor robes, and the accused would be allowed to sit beside their parents in the public gallery. The boys and their families would also be allowed to enter and exit the Criminal Courts of Justice, on Parkgate Street in central Dublin, through side entrances, and separate rooms would be provided for each of them where they could unwind and consult with lawyers during court downtime.

In accordance with the Children Act the general public would not be permitted at the trial, to protect the accuseds’ identities and to make the courtroom less intimidating.

Bona-fide journalists would be permitted in court. The murder and the investigation had attracted huge public interest, and the prosecution feared the court would be packed with reporters, negating any efforts to minimise the intimidating atmosphere.

They considered asking for a cap on the number of journalists permitted in court. Allowing them to view proceedings via video link, from another room, was also considered. In the end, the media would be asked to keep their numbers down, with the implication that the court would intervene if necessary.

Guilty pleas are extremely rare in murder trials, as the offence carries an automatic life sentence, no matter what approach the accused takes. As there is no sentencing discount for a guilty plea, defendants reason that they have little to lose by taking a chance on a trial. Even if the evidence is damning they may be acquitted on a technicality or because of an investigative deficiency.

The dynamic changes if the accused is a minor. The Children Act is silent on whether the automatic life sentence applies to children convicted of murder, but the prevailing legal opinion is that it does not and that judges may impose a lesser sentence if appropriate.

Before the trial Boy A’s lawyers concentrated on applying to have the indictment severed, which is to say having Boy A tried separately from Boy B. They reasoned that the jury was bound to be prejudiced against their client by hearing Boy B repeatedly accuse him, during his interviews, of attacking Ana.

The interviews of one defendant cannot be used against a coaccused. Boy A’s defence team argued that the jurors could not help but be influenced by the content of the interviews, even if they were warned it was irrelevant to the case against their client.

Their application before McDermott failed. “It would be a distortion of the factual background if the entire factual matrix of what happened in the lead-up to the death of Ms Kriégel was not set out in full to the jury,” the judge ruled, on April 12th. He said he would give jurors strong warnings about not relying on Boy B’s interviews when considering the case against Boy A.

Compared with Boy A, Boy B’s defence was much easier to predict. No forensic evidence linked him to the murder scene. In fact, the vast majority of the evidence against him came from his own mouth during his eight Garda interviews. If he had remained silent he would probably never have been charged.

The priority for Boy B’s defence was to minimise the damage done in those interviews, particularly by the many lies he had told detectives. Gardaí had stuck rigidly to the rules when questioning the boy, meaning there was little chance of getting the interviews excluded from the trial for the officers’ having been in any way coercive or oppressive.

In early 2019 his legal team asked Dr Colm Humphries, an experienced psychologist specialising in childhood trauma, to examine Boy B and the interview tapes. Having done so, Humphries diagnosed the boy with post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, as a result of witnessing the attack on Ana.

This PTSD contributed to the boy telling the gardaí untruths in an effort to protect himself, he wrote. The doctor said it was his opinion that Boy B had no knowledge of what was going to happen to Ana that day. He said the boy was sexually naive and had gone to the house with Ana and Boy A in the hope of watching them “snogging”.

The defence planned to call Humphries as a witness to explain that Boy B’s lies were the result of trauma rather than an effort to hide his guilt.

Calling him as a witness carried a risk, however. During Boy B’s sessions with the doctor he had given him information about what he saw in the abandoned house that day, information he had failed to give the Garda.

The boy told the doctor he saw Boy A standing over Ana with his trousers open during the attack. And that he saw Ana gasping before going silent.

If Humphries gave defence evidence he would likely be open to cross-examination on these matters, reinforcing the notion that Boy B continued to lie to gardaí up to his final interview.

The trial

It is not unusual for families of murder victims to sit through the trial of the accused. Often at least one family member remains in court for nearly all of the case, perhaps taking breaks during some of the more abstruse legal argument.

Few spend as much time in court as Geraldine and Patric Kriégel. Ana’s parents, accompanied by a victim-support volunteer, were present for every moment of the trial, from the swearing of the first juror to the final verdict.

When they wanted some water they would ask someone else to get it for them from the nearby canteen rather than leave court themselves. Geraldine took notes constantly, except when she held her husband’s hand during some of the more distressing evidence.

Pathology evidence can often be the most upsetting evidence for families to hear. But Geraldine and Patric remained throughout the testimony of Prof Marie Cassidy as she dispassionately described the autopsy process and the injuries inflicted on Ana. (Boys A and B were both excused from court that day because of the graphic nature of the evidence.)

There were several moments when emotion was visible.

A portion of Boy B’s interview during which he made a series of childish but nasty comments about Ana visibly distressed her parents. He said Ana was an outcast. She didn’t have a boyfriend and dressed in “slutty” clothes, he said. “I thought of Ana like a weirdo. Someone I should not be around.”

His description of seeing Boy A attack Ana in the house also upset her parents a great deal.

The accused sat beside one or both of their parents during the seven weeks of evidence. But they sat in different parts of the courtroom from each other and were never seen interacting.

During the lunch break they would go to the consultation rooms on either side of the entrance to court 9 while a family member fetched their lunch from the canteen.

In court Boy A often rested his head on his father’s shoulder. Boy B held his mother’s hand almost constantly.

The judge insisted on 15-minute breaks every hour or so. These were for the boys’ benefit but were probably just as appreciated by everyone else in court, especially on stuffy late-May afternoons.

The only major interruption came on the afternoon of day 15 of the trial, when a note was handed to the lawyers saying Boy B was having a panic attack. An ambulance was called, and court was adjourned for the day.

Boy B was treated at the scene and seen by his GP that evening. The incident occurred as the jury watched videos of Boy B’s Garda interviews during which he admitted lying to gardaí. No reason was given for the panic attack.

There was another interruption earlier in the day, when the defence had complained about someone in court staring at Boy B’s family at length and said it was distressing them.

From then on, the court day concluded at 2pm rather than 4.15pm. The new timetable would add at least a week to the trial but avoided the even lengthier delays that would have resulted from repeat medical issues.

It was decided at an early stage that the jurors would not come from the general panel that is called in the Criminal Courts of Justice every Monday to hear the week’s rape and murder trials. Instead a specially convened panel was brought in on Tuesday, April 29th.

The judge gave the jurors the usual warnings, such as not serving if they knew the parties in the case. Reading from a carefully prepared script, he also warned them the evidence was likely to be distressing.

Jurors were also advised they would be subject to criminal sanction if they disclosed the accused’s identities outside of court. This warning applied to everyone else as well, the judge said.

The warnings seemed to do their job; it appears the identities of the boys have to date not been shared publicly online.

During jury selection each side is allowed to object to seven jurors without explaining why. All three legal teams used this right liberally. The result was a jury of eight men and four women, all of them in at least middle age.

Ana’s parents were among the first witnesses to be called by Brendan Grehan, the prosecution counsel. As well as taking the jury through Ana’s last two days, Geraldine and Patric humanised her. Their descriptions of Ana’s personality and hobbies made her a real presence in the courtroom rather than an abstract piece of evidence. The jurors would never see any photographs of Ana alive, but they would have a clear picture of her in their minds.

Grehan also elicited detailed evidence of the bullying Ana suffered and the distress it caused her. The point was to show she was vulnerable and easily taken advantage of by the accused, he said.

Geraldine and Patric clearly found giving evidence emotional, but neither sought to make speeches or cast blame while in the witness box.

Their testimony was clear and calm. There was little hint of anger. The same was true for all four of the accused boys’ parents. All gave evidence of their interactions with the accused before and after Ana’s death, but none sought to use the witness box to proclaim the boys’ innocence. The furthest any of them went was Boy B’s father, who said his son was not capable of a crime like this.

Slowly but surely technology is becoming an intrinsic part of running a trial, and the trial of Boys A and B used it more than most. The seven child witnesses in the case gave evidence via video link from another room in the building, sparing them the distress and distraction of facing a live courtroom.

In the past the use of video link has been plagued by technical problems, with technicians often struggling to get the picture or sound working while a bemused jury looks on. It would seem those days are gone; all the children were able to give their evidence without interruption.

A significant amount of CCTV was played to the jury by Garda Seamus Timmins. Nothing new there, except in this trial the location of CCTV cameras was shown concurrently on a digital map of the area, making it easy for jurors to determine where exactly the accused were when captured on film. Grehan would play this footage again when making his closing speech.

Also helpful was the use of a computer-generated 3D model of Glenwood House, which was created by Forensic Science Ireland and the Garda photography and mapping units.

The locations of objects such as the suspected murder weapons and Ana’s clothes, as well as of the blood spatters, were shown in the model beside their photographs. It gave the jury the closest possible sense of being at the scene without having to visit the house.

The 3D modelling programme has been used just once before, in the 2017 prosecution of two brothers for murder. Ironically, during that trial Grehan, who was defending one of the accused, objected to the use of the 3D model on the basis of its being untested.

For such a complex case, involving so many strains of evidence, the trial was conducted with remarkable efficiency.

Defence concessions in several aspects in the case, including the lawfulness of the boys’ custody and the gathering of evidence, meant many potential Garda witnesses were not required to give evidence.

Those Garda witnesses who were called often spent only a few minutes in the box. Early in the trial, five or six witnesses were sometimes called in a single day.

Part of the reason for the pace was the lack of cross-examination from the defence. More often than not, Patrick Gageby, for Boy A, and Damien Colgan, for Boy B, declined to ask the witnesses any questions.

This made it difficult to discern the nature of the boys’ defence until very late in the case, but some of the few questions counsel posed gave a little insight into their strategy.

Gageby asked Geraldine Kriégel if her daughter was sexually active. She replied that she wasn’t, a point confirmed by later medical evidence.

Colgan asked Prof Cassidy if someone who witnessed that attack on Ana would be traumatised. She agreed that they would be.

Det Gardaí Daly and Gannon were questioned at length by Colgan about the way they interviewed Boy B. Gardaí didn’t bring in specialist interviewers or give the boy regular breaks, counsel said. The detectives replied that they stuck to the rules and that the boy’s mother was with him at all times.

In the absence of the jury

Much of the defence work focused on persuading the judge to include evidence that was favourable to the accused while excluding evidence that painted them in a negative light.

For Boy A, the most important evidence to exclude was the forensics. Gageby argued that the testing of his client’s boots, on which Ana’s blood was found, was inadmissible, as gardaí had taken the boots under false pretenses. He submitted that gardaí had pretended to take the boots to investigate his claim of being assaulted by two men but were actually taking them to investigate Ana’s disappearance. He made the same argument for Boy A’s phone.

Det Garda Gabriel Newton said she took the boots and phone solely because they might help her to find Boy A’s attackers. She said she didn’t even know Ana was dead at that stage.

The judge agreed with Newton, and the defence application failed.

Next Gageby argued the DNA evidence against Boy A was inadmissible because Supt Gordon had filled out the wrong form to authorise the taking of samples from the boy.

Called to give evidence, Gordon conceded that, instead of filling in an authorisation form under the 2014 DNA Act, he filled in one concerning the 1990 Act. The prosecution said it was a record-keeping error but no more. The detectives who took the samples gave evidence that they were correctly instructed under the 2014 Act. Again the defence application failed.

One of the main objectives of Boy B’s defence team was to have the jury hear the evidence of Dr Humphries, the psychologist who examined the teen at the start of the year and determined he had been traumatised by witnessing the attack on Ana.

In the absence of the jury, Humphries repeated what he said in his report, that the trauma caused Boy B to tell the gardaí “untruths”. The doctor said he didn’t like to use the word “lie” because he didn’t want to seem judgmental.

He told Colgan the boy was bright but naive and immature. By way of illustration, he said that, during his stay in Oberstown, Boy B had asked for Lego to play with – a request the staff had never had before.

Grehan’s cross-examination of Humphries for the prosecution was easily the most combative of the entire trial. Counsel took particular issue with the doctor’s assertion that Boy B had “no knowledge of a plan for murder”.

Grehan said this was a matter for the jury. He said the doctor’s report contained a lot of jargon but there “doesn’t appear to be any engagement with the facts of the interviews”.

He submitted that allowing the doctor’s evidence into the trial would trespass on the function of the jury as the judges of fact and effectively make Humphries a “13th juror”. After taking the night to think about it, McDermott excluded the doctor’s evidence entirely.

But the prosecution did not enjoy an unbroken record of success in their legal applications. In fact a significant number of the judge’s other decisions ended up going against them, including one concerning a novel attempt to introduce photographs of a mannequin into evidence.

Horror movies and heavy metal

There is a long history of prosecutors deploying unusual exhibits in criminal trials. In 2010 a bodhrán was presented in the Special Criminal Court to prove the accused was a member of the IRA. During the Troubles a packet of digestive biscuits was presented in the same court; prosecutors argued it was a component of a home-made mortar.

Striking exhibits can be especially helpful in murder trials. Juries have been shown swords, spades, guns, bats and, in the 2008 trial of Brian Kearney, for strangling his wife, a vacuum-cleaner flex. Such exhibits can help juries visualise how a crime may have been committed far better than any description from a witness.

That was the idea behind the prosecution’s plan in this case to dress a mannequin up in the clothes worn by Boy A during Ana’s murder and present photographs of it to the jury. Pictures of the mannequin, fitted with the mask, gloves, snood, shin-guards and knee pads found in the boy’s backpack, would be shown to jurors.

It was, to say the least, an unusual request. The prosecution knew McDermott would need to be convinced of the merits of bringing such an unusual exhibit into a courtroom. It would essentially be showing the jury the last thing Ana saw before her death.

At the midpoint of the trial, in the absence of the jury, Grehan handed the judge three photographs of the mannequin, which had been dressed by a Forensic Science Ireland expert, John Hoade.

The barrister said it would be nothing more than a “visual aid” to show the jury how items from the backpack were intended to be worn. He said the mannequin was “no more than a representation of what the jury has already seen, in a different format”.

Gageby, for Boy A, objected on the basis that the mannequin was speculative and there was no evidence it accurately portrayed what was worn at the time. For example, there was no evidence to show Boy A had his hood up during the attack.

Mr Justice McDermott tends to look at barristers over the top of his spectacles when he is sceptical of their argument. This is what he did as the prosecution tried to get the mannequin photographs admitted.

“Whatever limited probative value is outweighed by the disproportionate prejudicial effects. I’m not satisfied that this photo should go in,” he ruled.

McDermott would use the same reasoning, combined with the quizzical over-the-glasses look, throughout the trial when denying the prosecution permission to admit other evidence.

Most of the legal wrangling was over the items obtained during the search of Boy A’s home after his arrest, including a copybook whose drawings and scribblings included a sketch titled Nightcrawler, showing an emaciated figure with a bandaged skull for a head. The words “just kill them” and “just f**king do it” were also written in the book.

This showed an interest in violent imagery, the prosecution said.

The copybook also contained instructions for constructing a “shell mask”, proof the mask found in the backpack was made by Boy A, they said.

The judge allowed the mask-making instructions but excluded the other items. “I’m trying to tie it in with the case, but I don’t see it,” he told Grehan. “He had a portfolio of material. That seems to be, on its face, the height of it.”

Next up was a completed questionnaire, signed by Boy A, that appeared to form a part of a school assignment. It read:

Where do you like to hang out? Abandoned places.

What are your favourite books? Horror.

What are your favourite sports? Combat.

What are your favourite movies? Horror and comedy.

What are your favourite music? Rap and heavy metal.

Single or taken? Single.

I would describe myself as: Crazy, funny, adventurous.

I am: strange

I think: differently

I feel: not much

I hope to: do well in life

I feel: angry when someone tries to annoy me or hits me

I love: steak and drawing.

I hate: homework.

Aside from the obvious relevance of liking to hang out in abandoned places, the prosecution said the answers gave an insight into how the accused viewed himself, as someone who is “strange”, thinks “differently” and doesn’t feel much.

“These are teenage documents,” McDermott said. “Lots of teenagers watch horror movies and listen to heavy metal.”

Gageby called them “juvenile jottings of a juvenile written in a juvenile fashion as part of some class of a school questionnaire”.

He continued: “The fact he feels himself strange or doesn’t feel much is likely to be taken out of context and in some way demonstrate that it is more likely that the author of this planned and killed a young girl. In my opinion it just isn’t there.”

The judge ruled out every part of the questionnaire except for the reference to hanging out in abandoned places.

Among the most contested evidence was the huge amount of pornography found on Boy A’s electronic devices.

The prosecution sought to introduce as evidence 10 of the images that depicted sexual violence, as well as the pornographic video mentioning “Anastasia” (not Anastasia Kriégel) in its title. The violent material could be relevant to the boy’s attitude towards consent, he said.

“It is general background evidence. That’s as far as we go with it. It is potentially relevant in that regard,” Grehan said.

Gageby countered that the probative value of the pornography evidence “is so slight as to be imperceptible” while its “prejudicial value is extremely high”. If the prosecution wanted to introduce the violent images, they might have to put them in context by introducing the thousands of other nonviolent images, he suggested.

It was also inadmissible because of the six-month gap between the material being accessed and the murder, Gageby argued.

McDermott agreed, ruling that admission of any of the pornographic material would be unfair.

Also ruled out was a video found on Boy A’s phone that appeared to show Boy B hitting a stone block with a steel-reinforced stick. “Holy shit. That’s f**ked,” Boy A could be heard saying as he zoomed in on the damage caused to the block.

“I don’t see any relevance other than attempting to draw an inference which could not be justified,” McDermott ruled.

He made the same ruling about evidence of internet searches by Boy B for various types of knives and for a Youtube video entitled My Girlfriend Tortured, Stabbed and Starved Me.

Among the vast amount of evidence collected by gardaí were several references to satanism. In Boy B’s room gardaí found a copybook laying out the rules of a “satanic cult” he had set up. There was a list of the group’s members, including both accused, as well as the cult rules:

“Only pledge hosts can give pledges.

“Don’t talk about it.

“Act normally like nothing happened.

“No talking about Jesus or God, only Satan.”

Unprompted, Boy B had told gardaí during his sixth interview that the “cult” was actually a homework club. Participants would share their homework with each other if they had forgotten to do it, he explained. The reference to satanism was to dissuade other classmates from wanting to join.

Satanism arose again when, during one interview, Daly asked Boy B if May 14th, the day Ana was murdered, had any relevance. “That’s doomsday, isn’t it?” the detective asked.

Before the interview Daly had put the date into Google and was brought to a website called Satan’s Rapture, which featured a calendar stating the world would end on May 14th. The boy said the date held no significance for him and he was not familiar with the satanic calendar.

At another point in his interviews, Boy B described seeing a “pentagram”, a symbol associated with satanism, in Glenwood House.

Before the start of the case prosecutors and investigators debated the relevance of the references to satanism. Detectives had discovered little to no evidence of motivation for Ana’s murder; perhaps an interest in the occult might provide an explanation. In the United States in the 1980s a series of violent crimes was linked to satanism, leading to what became known as “satanic panic” among the public. (It was later established that many of the crimes had little or no link to satanism.) Closer to home, the murder of a seven-year-old boy in 1973 in Palmerstown, in west Dublin, was suspected by some investigators as having a satanic link.

There were several drawbacks to the satanism theory, however. Pentagrams, like crudely drawn swastikas, are commonly used to deface derelict buildings, and Boy B’s homework-club explanation for the “cult” was corroborated by several classmates.