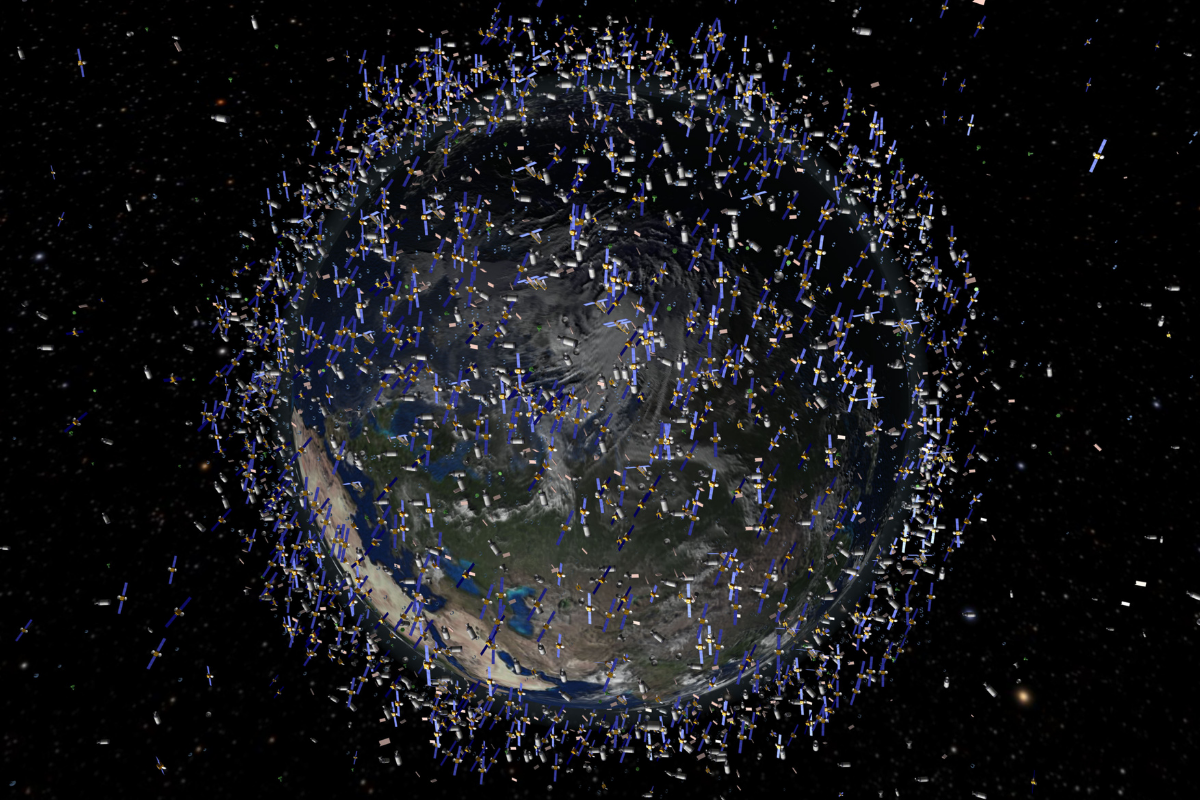

They say what goes up must come down. When it comes to space, however, this expression doesn’t ring so true with space debris now reaching crisis proportions.

In fact, there are currently around 28,600 debris objects tracked by space surveillance networks and many more objects not able to be tracked at all.

However, regulating the use of space and keeping countries accountable for debris, is no easy feat, said Steven Freeland, Emeritus Professor at Western Sydney University and Professorial Fellow at Bond University specialising in Space Law.

“I’m not saying it’s impossible, and that we should just throw our hands up and wait for disasters to happen,” he said. “There’s a lot of discussion and a lot of work being done already, but it’s not easy and that’s really the point.”

Although Australia is not a top contender in the global space industry, Celine D’Orgeville, Professor at the Australian National University, sees Australia having a strong political influence in global discussions.

“There is room for Australia to take a little bit of leadership and guide this conversation at the policy level, I don’t know if Australia will do it but there is an opportunity,” she said.

As each year more satellites are sent up to space, our reliance upon this technology increases. From Wi-Fi to online banking, if a major collision was to knock out functioning satellites our lives would be dramatically changed, Professor Freeland said.

“So, to the extent we continue on a ‘business as usual’ basis to create unacceptable amounts of additional debris to the point where we create irreversible damage, or at least for generations and generations, then that will have devastating effects on the world, the economy, lifestyles, infrastructure; in essence, everything about the functioning of our society may collapse.”

While countries are entering legal discussions in an attempt to regulate the use of space, researchers are investigating potential ways to mitigate collisions and ‘clean up’.

However, even new technologies can’t escape the inherently political nature of space exploration.

Professor Freeland said many countries are concerned.

“If you develop the technology to clean up the debris – and that technology will be essential – we still need to deal with the lingering question as to how to prevent you from using that technology to grab my ‘live’ satellite, upon which I am dependent, which would of course, compromise my ability to function,” he said.

“The issue is intensely legal and it’s intensely political. You can’t separate the two.”

Professor D’Orgeville said doing technology in space is not difficult, but it’s something we can do and learn to do better.

“Doing it well and preserving space, that’s the political dimension and it’s definitely, from my point of view as a scientist, more complicated,” she said.

This story, originally published by Central News, a multi-platform news service based at the University of Technology Sydney, has been shared as part of World News Day 2021, a global campaign to highlight the critical role of fact-based journalism in providing trustworthy news and information in service of humanity. #JournalismMatters.