To mark World News Day on September 28, 2022, the World News Day campaign is sharing stories that have had a significant social impact. This particular story by Fiona Sun (Edited by Emily Tsang and Alan John) — with visual storytelling by Adolfo Arranz, Marcelo Duhalde, Kaliz Lee, Han Huang and Dennis Wong — was shared by the South China Morning Post (Hong Kong).

In the second of a three-part series on Hong Kong’s subdivided flats, Fiona Sun looks at the physical and mental toll on tenants of the city’s most inadequate housing. Beijing has set the city government the target of getting rid of these tiny units and ‘cage homes’ by 2049.

Siumei* prepares dinner in the living room of the 100 sq ft space she calls home in Mong Kok, while her seven-year-old son does his homework at a massage bed near her.

The 42-year-old divorcee lives with her son and widowed mother, 70, in a subdivided unit too small to have a separate kitchen.

The adults eat at a small foldable table, while the boy has his meal on the bed, with a line of drying laundry hanging over him.

After dinner, Siumei plays with her son on the floor while her mother watches TV. Sometimes the three go for a walk outside to leave their tiny space for a while.

Their 10 sq ft bathroom, most of which is occupied by the toilet and sink, is so small that Siumei must stand outside to help her son bathe. The blocked drainage means they can only shower for less than five minutes at a time, or smelly waste water will flood the floor.

Siumei and her son share the upper berth of a bunk bed, while her mother sleeps below. They are occasionally startled by rats, which have chewed into their wooden furniture. Cockroaches and dragonflies are common.

One window opens to a podium of stinking garbage, so it is kept closed. Poor ventilation makes their home stuffy, but they switch on the air conditioner only at night to save electricity.

“When my son asked why we live in such a tiny, poor place, I can only tell him I was too poor to afford a bigger home,” says Siumei, who came to Hong Kong from Guangdong after meeting a Hongkonger.

The couple married in 2009 but divorced six years later.

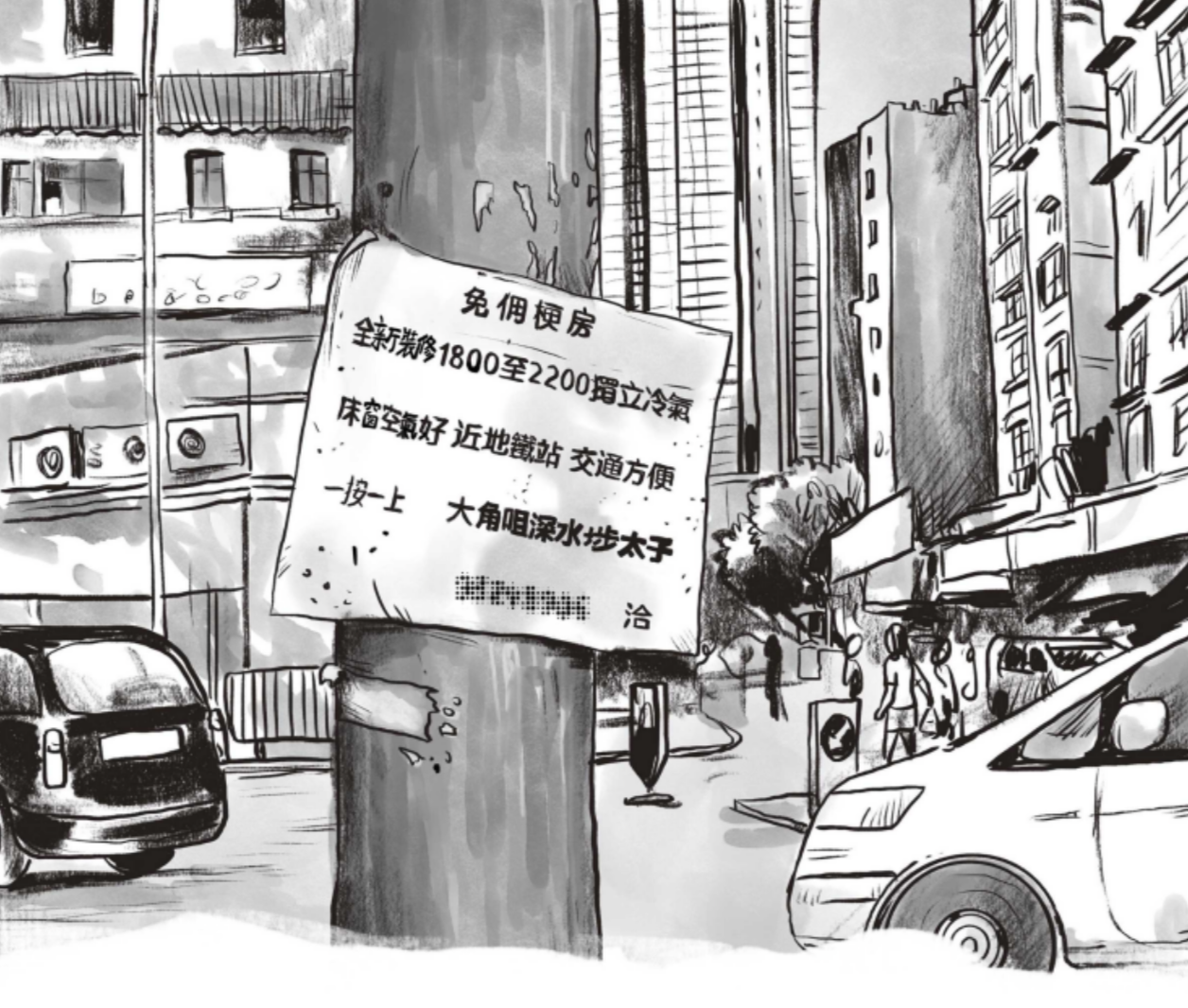

She pays about HK$4,000 (US$513) a month for their unit in a seven-storey tenement building that is more than 50 years old. The amount is more than half her monthly income working part-time at a restaurant.

“I feel so burnt out and helpless, but I don’t even have room to vent my emotions,” she says.

Hong Kong has about 110,000 subdivided units ranging from 20 sq ft to 200 sq ft, and they are notorious for their substandard conditions, poor hygiene and fire and security hazards.

The poor environment has taken a heavy toll on the physical and mental health of the more than 220,000 people who live in them.

Flimsy partitions, fire hazards

Most subdivided units are in dilapidated tenements, many of which are dubbed “three nil buildings” because they are without owners’ corporations, residents’ organisations or property management companies.

The findings of a survey released by the Transport and Housing Bureau in March last year showed that concerns about electricity supply, law and order, and the lack of a fire escape were the top sources of dissatisfaction among subdivided unit tenants.

Professor Yau Yung, of Lingnan University’s department of sociology and social policy, says the subdivision of flats often results in narrow, long and blocked escape routes, and poor ventilation makes it hard for smoke to disperse.

Some partitions are not fire-resistant and, without access to kitchen facilities, cooking over an open flame within the units is a fire hazard.

The Buildings Department warns that work to remove original walls and install new partitions to create subdivided units or add toilets and kitchens may adversely affect safety and hygiene, and put tenants’ lives at risk.

The department issued 1,913 removal orders for such works from 2016 to 2020, for flouting the Buildings Ordinance. It issued 475 orders last year, and 18 in the first three months of this year.

The operation of the city’s tiniest bed spaces, known as “cage homes”, is regulated by the Bedspace Apartments Ordinance.

The Home Affairs Department says the number of licensed bed space apartments fell from 15 in 2011 to nine this year. They included six in Yau Tsim Mong district, and one each in Central and Western, Eastern, and Sham Shui Po districts.

But social workers say many more cage homes as small as 20 sq ft are available in unlicensed flats that go unrecorded.

‘Inhuman conditions’

Yau Sai, 68, pays HK$2,000 a month for his boxlike compartment in an unlicensed bed space flat he shares with 18 other men and women in Mong Kok.

Returning at night from his job at a food factory in Tsuen Wan, the single man, who asked to be identified only by his given name, unlocks his unit and climbs into it, taking care not to hit his head.

The flat is stacked floor-to-ceiling with three-layered boxes separated by wooden boards, each big enough for one adult to lie in.

Yau Sai’s mid-level space keeps him sandwiched between tenants above and below him. A tall man of 180cm, he cannot stretch out as half his space holds his personal belongings.

There is a small kitchen and three bathrooms. A tenant used to be paid by the landlord to clean the common areas, but that stopped, leaving the bathrooms dirty.

For privacy, Yau Sai keeps his compartment door closed, but that does little to block the sounds of other tenants chatting, making phone calls or watching TV.

He browses his mobile phone for the news and to watch videos before bedtime, but is sometimes startled when the tenant above him hits the wooden boards accidentally.

A bad night’s sleep can leave him with an aching back the next day. He makes sure to lock his unit and take all his cash and bank cards with him when he leaves the flat.

“It’s inhuman to live in such conditions,” he says, adding he cannot afford anything better on his monthly income of about HK$10,000.

According to a report on the quality of living in subdivided units released by the Society for Community Organisation (SoCO) last August, almost all 347 households surveyed complained about hygiene problems.

Many subdivided flats had rats, mosquitoes and bugs. Many units had a makeshift kitchen installed in the living room or a bedroom.

Wrongly connected water pipes smelled bad, and water seeped through walls or from the ceiling. Poor ventilation was common, and some units had no windows.

In another SoCO survey of 385 households living in cage homes and cubicles in 2020, one in three said they did not feel safe having to stay at home during the Covid-19 pandemic and feared contracting the virus.

More than half shared a toilet with seven to 10 others – with some using the same toilet with as many as 16 to 20 others – and there were complaints that common areas such as the kitchen and bathroom were not cleaned during the pandemic.

Impact on physical, mental health

Living in such poor conditions affects tenants’ physical and mental health, social workers say.

A survey conducted between 2020 and 2021 by the NGO Caritas Community Development Service of 527 households living in inadequate housing, including subdivided units, asked tenants to score their physical and mental well-being on a scale of up to 100.

Three in five scored below 50 for physical health, and more than nine in 10 scored below 50 for mental health.

Many suffered muscle strain, cardiovascular diseases and respiratory problems, as well as mental disorders, and some blamed their poor living conditions.

Wong Siu-wai, the NGO’s senior social work supervisor, says children living in subdivided flats face higher risks of eye problems because of a lack of natural light, and many have spinal problems from studying in bed.

“Housing has a significant impact on people’s physical and mental health,” she says.

The Kwai Chung Subdivided Flat Residents Alliance, made up of residents living in such units in Kwai Chung and social workers, found in a survey last year that about three in four of 78 people living in inadequate housing units suffered moderate to severe depression, and more than two in five had moderate to severe anxiety.

Social worker Poon Wing-shan, a member of the alliance, says sharing small spaces often leads to conflict and there is no escape for tenants at home. They are also burdened by their rent, which accounts for about 40 to 50 per cent of their income.

She says tenants live in a constant state of insecurity, subject to rent increases and utility charges by landlords, and fear being kicked out at any time.

Some who are parents feel guilty for being unable to provide their children a better living environment.

“They regard living in subdivided units as a failure,” Poon says. “None of them thinks of their unit as home, and they view themselves as passers-by with no roots.”

‘No sense of belonging’

Housewife May Lau, 34, feels too ashamed to tell anyone where she lives with her husband, a renovation worker from mainland China who is also 34, and their five-year-old daughter.

“Living in a subdivided unit makes me feel inferior to others,” she says.

The family moved into a 150 sq ft subdivided unit in Kwai Chung for HK$6,300 a month in June last year after living with her parents at their public rental flat in the same area.

But with her husband’s monthly income of about HK$14,000 – below the city’s poverty line for a three-person household – they could not afford anything bigger.

Their unit is one of the three within a flat and has no separate bedroom or kitchen. There is no space for a sofa or television, and they eat at a small, low table. All three squeeze themselves on the lower berth of a bunk bed, keeping their belongings piled above.

Her daughter, a kindergarten pupil, complains that there is no room to play and asks to return to her grandparents’ home.

Her husband’s parents in mainland China also blame her for the family’s poor housing, and Lau says she has stopped seeing some friends who look down on her because of her circumstances.

Alone at home, she is sometimes overwhelmed worrying their rent might go up, and fearing the impact of the family’s poor living conditions on her daughter.

“It is not a home. I have no sense of belonging here,” Lau says.

*Name changed at interviewee’s request.