Fernanda Buriola was born and raised in São Paulo, Brazil but now lives in Luxembourg. She has been writing for her own newsletter, Manhãs, for almost six years. Previous contributions were featured in the french magazine Zéphyr. She is most interested in writing about behavioral and natural science.

I was scrolling through Instagram, trying to escape reality for just five minutes, when I first came across the word “eco-anxiety.” I’d never heard the term before. Yet, the more I learn about it, the more I recognize the feeling.

I’ve been following Finn Harries for a long time now. He’s a designer and environmentalist. I don’t know anything about design, but I like his content on how architecture can respond to the climate crisis. Last summer, he posted the following message: “I’ve been battling with my mental health over the last couple of months. A big part of it is driven by the environmental crisis we’re facing. This even has its own term: eco-anxiety.”

Seeing Harries’s post, I paused to consider if I myself was eco-anxious. Of course, I care about nature, but I don’t lose any sleep over it. I figured climate scientists on the front line were the ones having a hard time, witnessing the realities of climate change on a daily basis and not being listened to. I never realized I could be having a hard time too.

Pain For The World

Lynda Sullivan, an Earth activist from North Ireland, told me she defines eco-anxiety as a “pain for the world.” The American Psychological Association, a reference for psychologists, defines it as “a chronic fear of environmental doom.”

According to a survey conducted by Sintra, a Finnish Innovation Fund, in 2019, a quarter of Finns experience some form of climate anxiety. Back in January, a YouGov poll said seven in ten young adults aged 18-24 in the U.K. were more worried about climate change than the previous year.

Official data and studies on eco-anxiety remain scarce. Nevertheless, in the last decade discussions on the effect of climate change on our mental health have finally started to get the attention they deserve.

Am I Eco-Anxious?

I’ve been struggling with my mental health since I moved to Belgium from São Paulo eight years ago, but I can’t tell how much of my struggle has been linked to the climate crisis. Worries about the world blend with worries about my own life.

When I was younger, I wanted to be a scientist of some sort: an ecologist, perhaps, or an oceanographer. I imagined myself learning more and more about nature, not only because Biology was my favorite subject at school, but also because a career as a scientist meant I could do something to reverse climate change.

I also wanted to be like my cousin. She is a biologist and the older sister I never had.

When it was time to decide on a career, I chose to act against climate change professionally by studying Biology. It was my first, small attempt to change the world—a desire common among young adults, my therapist tells me.

Over time I realized that nature doesn’t need saving—we do. Planet Earth will continue to spin, ecosystems will eventually regenerate, though maybe not back to how they were before. Now I fear what will happen to people, starting with the most vulnerable. Global warming, I realize, is a social issue.

Perhaps I would have finished my studies if I had been in Brazil, but in Europe, it proved almost impossible without the support I needed. At university—in a new country and culture, speaking a new language—I was at my most depressed. Completely alone, academic frustration merged with personal worries.

“I can do so much and yet so little. Does that make me eco-anxious?”

You can’t take care of the world if you’re on the wrong path. I changed mine—from Biology to Communication—yet my place on this planet remained a mystery. It is hard to feel useless when there is so much to be done.

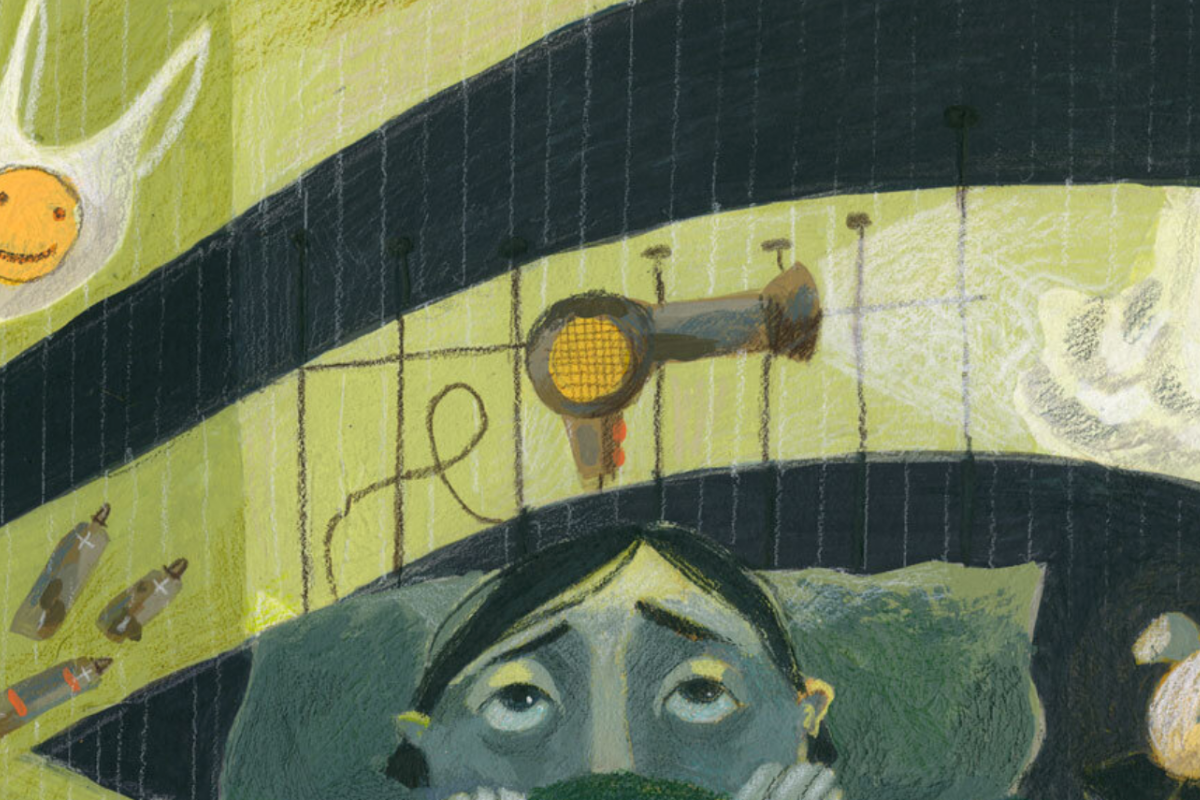

As a response to my concerns, I put a lot of energy into controlling what was within my reach: what I consume, the waste I produce, what I eat. Everyday choices can leave me anxious and feeling guilty. There are days when this turns into hopelessness. I can do so much and yet so little. Does that make me eco-anxious?

A Spectrum of Emotions

I spoke to Caroline Hickman, a climate psychologist and researcher at the University of Bath, about my life choices, slightly compulsive recycling, and how my everyday fears for the planet, though scary, seem normal to me. Climate change was on the news before I was born, after all.

Hickman kindly explained that “anxiety is just one of the feelings people are dealing with [about climate change]. People are also struggling with despair and frustration and hopelessness.” So eco-anxiety might not be the best term; it is a catch-all for a whole range of feelings.

“Eco-anxiety is unlike ordinary anxiety, like worrying about finances or an exam, because this particular problem is not going away.”

If I can’t make the big important decisions, what can I do? That question can trigger in me a meticulous rethink of what I really want and need given the impact on the planet, or make me walk multiple blocks until I find that zero-waste store. But sometimes all the overthinking pauses and I find myself buying food in the closest shop. “These feelings come and go,” Hickman reveals, “but they don’t go away.”

Eco-anxiety is unlike ordinary anxiety, like worrying about finances or an exam, because this particular problem is not going away. Take the recent pandemic, for instance; no matter its impact on our lives, we are still capable of imagining a world without COVID-19 once a vaccine is developed. Similarly, most disgruntled employees can imagine getting a promotion or switching jobs. Life works in phases, usually. But if we can’t curb our carbon emissions fast, global warming will be a life-long, worsening reality for many of us, especially us younger generations, making it nearly impossible to envision a future without climate change.

A Normal Reaction to a Sick Planet

“Climate anxiety can be a problem if it is so intense that a person may come paralyzed,” researcher and professor of environmental theology at the University of Helsinki, Dr Panu Pihkala, wrote in a 2019 report, “but climate anxiety is not primarily a disease.”

Nonetheless, the report lists severe symptoms (states of depression, serious insomnia, compulsive behavior) and mild ones (occasional insomnia, effects on mood, milder symptomatic behavior). “Climate anxiety is combined in people’s lives with other anxieties,” writes Dr Pihkala, “such as those related to choosing a profession.” In case something else is causing deeper anxiety in a person’s life, he argues, climate anxiety should be taken seriously to better evaluate the overall situation.

In the U.K., Professor Hickman is now working to increase awareness among psychotherapists, doctors and teachers “so they can understand people’s distress through the lens of climate emergency.”

Action is no doubt the best solution, for the planet and ourselves. Putting ourselves to work can ease our minds. But are there other forms of self-care? As an exceedingly self-critical person, I was relieved to hear Hickman say we shouldn’t criticize ourselves for feeling out of balance. Easing up on the self-criticism, she told me, is a genuine way to look after ourselves.

“When feeling blue, it’s good to remember we are doing what we can. Or at least trying to.”

Like everyone I’ve talked to, she also agrees that eco-anxiety is a normal and understandable reaction to the problems we are facing. If you are in the habit of consuming information on climate change, it’s only natural you feel anxious about the existential threat it poses to humanity. “It is the people who are not anxious and angry that I would worry about,” she says.

When feeling blue, I believe, it’s good to remember we are doing what we can. Or at least trying to.

For Hickman, that means raising awareness about the emotional challenges of climate change. That, she tells me, is how she deals with her own anxieties.

In the final line of his Instagram post, Harries wrote: “We may be in a time of crisis but I’ve realized looking after our mental health and building our resilience is the first step to long term, meaningful action.”

This story, originally published by Are We Europe, has been shared as part of World News Day 2021, a global campaign to highlight the critical role of fact-based journalism in providing trustworthy news and information in service of humanity. #JournalismMatters.