To mark World News Day on September 28, 2022, the World News Day campaign is sharing stories that have had a significant social impact. This particular story was shared by The Star (Malaysia).

Malaysia is becoming an increasingly ‘male country’, with males increasingly outnumbering females over the decades.

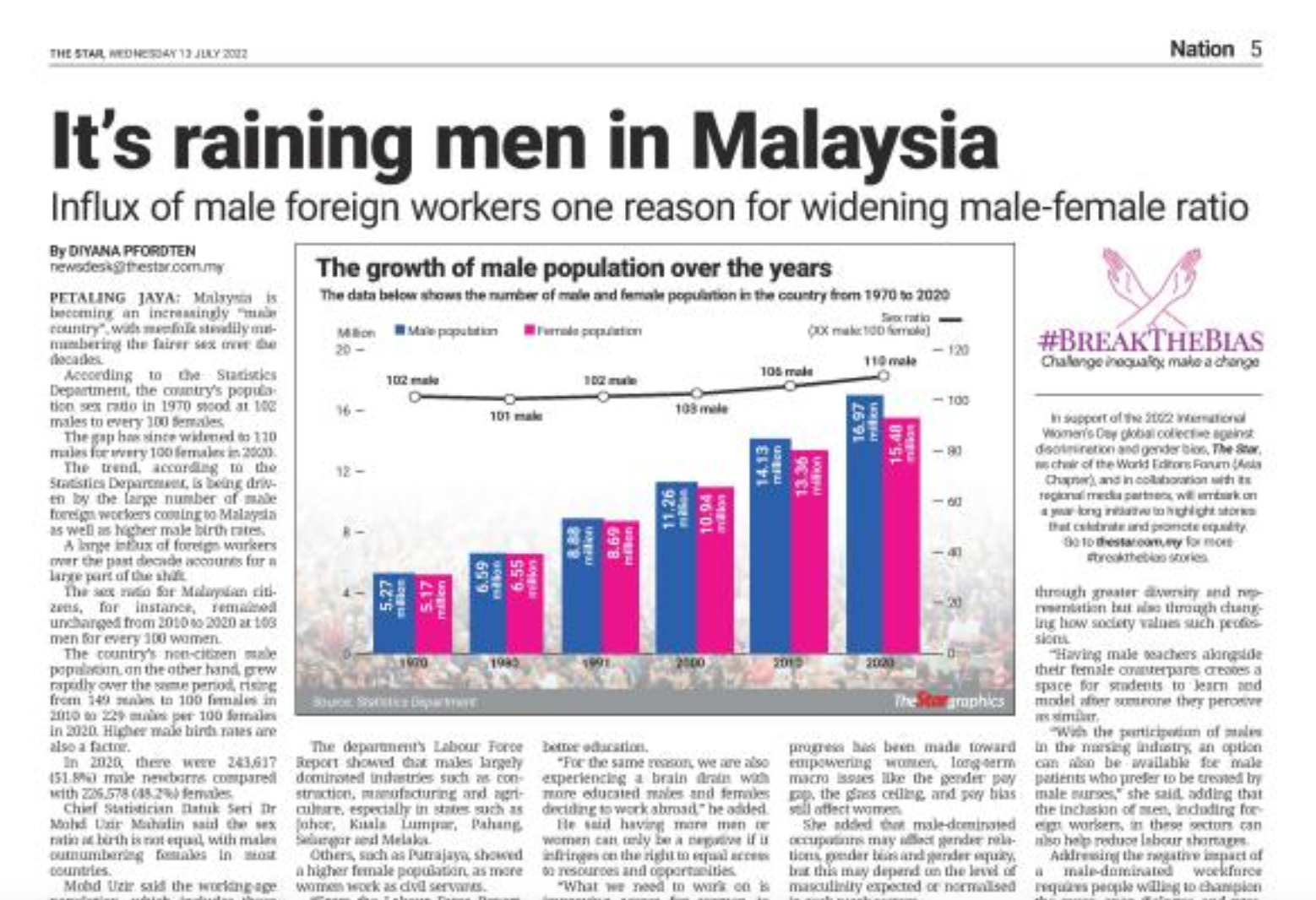

According to the Statistics Department, the country’s population sex ratio in 1970 stood at 102 males to every 100 females.

The gap has since widened to 110 to every 100 females in 2020.

The trend, according to Statistics Department, is being driven by the large number of male foreign workers coming to Malaysia as well as higher male birth rates.

A big influx of foreign workers over the past decade accounts for a large part of the shift.

The sex ratio for Malaysian citizens, for instance, remained unchanged from 2010 to 2020 at 103 males to every 100 females.

The country’s non-citizen male population, on the other hand, grew rapidly over the same period, rising from 149 males to 100 females in 2010 to 229 males per 100 females in 2020.

Higher male birth rates are also a factor.

In 2020, there were 243,617 (51.8%) male newborns compared with 226,578 (48.2%) females.

Chief Statistician Datuk Seri Dr Mohd Uzir Mahidin said the sex ratio at birth is not equal, with males outnumbering females in most countries.

Universiti Putra Malaysia’s Malaysian Research Institute on Ageing (MyAgeing) research officer Chai Sen Tyng said the excess of male births has been widely documented and consistent across populations around the world, with 103 to 107 boys born for every 100 girls.

“But in countries like China and India, the cultural preference for sons and a combination of population policy and use of ultrasound for sex determination have resulted in highly skewed sex ratios.

“The United Nations World Population Database showed that the sex ratio at birth (male births per 100 female births) for China and India in 2020 was 111 and 110 respectively, compared with 106 for Malaysia, Brunei, Philippines and Thailand,” he added.

Mohd Uzir said the working-age population, which includes those between 15 and 64 years old, was also dominated by males at 52.9% as compared with women at 47.1%.

“The sex ratio in each state depends largely on the factors of labour force and socioeconomic status.

“There are many males working in the construction and agriculture sectors,” he said.

The department’s Labour Force Report showed that males largely dominated industries such as construction, manufacturing and agriculture, especially in states such as Johor, Kuala Lumpur, Pahang, Selangor and Melaka.

Others such as Putrajaya showed a higher female population, as more women work as civil servants.

“From the Labour Force Report, the sex ratio for civil servants in Putrajaya in 2020 was 61 males compared with 100 females,” Mohd Uzir said.

Citing research by Schact, R and Kramer, K titled “Too many men? Too many women? Effects of sex ratio imbalance on marriage and family formation”, Mohd Uzir said having a male-biased population may impact social stability.

“From a socio-demographic perspective, male-biased sex ratios leave many men unable to find a partner and so elevate competition among males, disrupt family formation, and negatively affect social stability,” he said.

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia’s Critical Media Studies Assoc Prof Dr Jamaluddin Aziz said the influx of foreign workers taking up lower-paying jobs is inevitable as a country’s population becomes better educated.

“For the same reason, we are also experiencing a brain drain with more educated males and females deciding to work abroad,” he added.

He said having more men or women can only be negative if it infringes on the right to equal access to resources and opportunities.

“What we need to work on is improving access for women to quality resources so that they can be more competitive in the face of global challenges,” he said.

MyAgeing deputy director Assoc Prof Dr Rahimah Ibrahim said policies, workplace procedures, and societal norms have generally been orientated to and with intended benefits for males.

“This will continue unless something is done about it,” she said.

She said despite some developments in terms of female empowerment, long-standing macro issues still affect women, including the gender pay gap, the glass ceiling, and pay bias.

“As such, women have to work even harder to create awareness and make changes to turn things around,” she said.

She added that male-dominated occupations may affect gender relations, gender bias, and gender equity, but this may depend on the level of masculinity expected or normalised in such work sectors.

“Studies have also found that men in male-dominated industries face greater risks of work-related injuries and deaths and higher rates of suicides,” she said.

She said to a larger extent, the workforce and society are still structured around traditional gender roles.