To mark World News Day on September 28, 2022, the World News Day campaign is sharing stories that have had a significant social impact. This particular story by Fiona Sun (Edited by Emily Tsang and Alan John) — with visual storytelling by Adolfo Arranz, Marcelo Duhalde, Kaliz Lee, Han Huang and Dennis Wong — was shared by the South China Morning Post (Hong Kong).

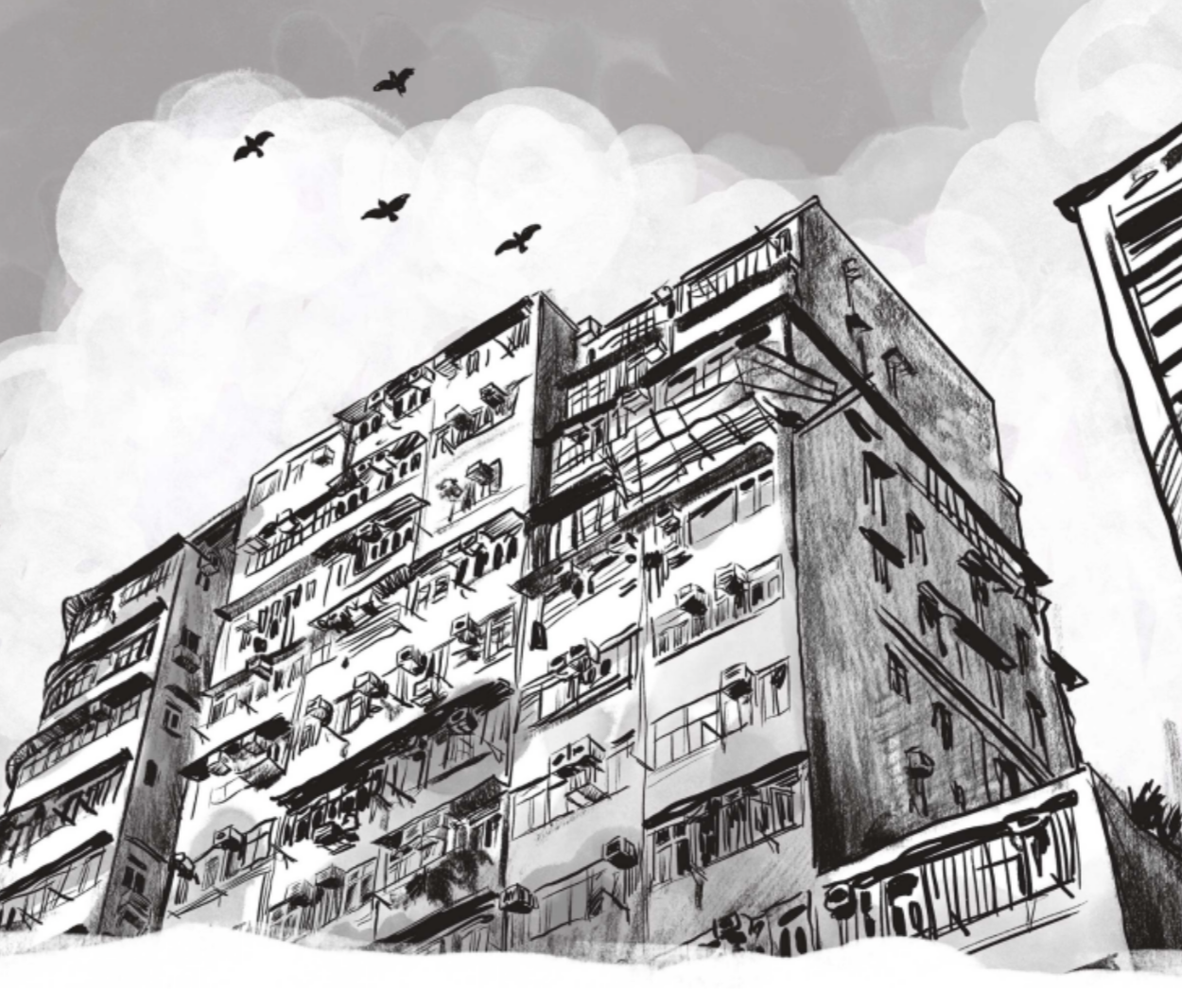

Hong Kong’s poor and destitute have long been unable to afford anything but subdivided living spaces. Now Beijing wants the local government to rid the city of these tiny units and “cage homes” by 2049. John Lee Ka-chiu, who will be sworn in as the city’s next leader on the 25th anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to Chinese rule on July 1, has pledged to resolve housing woes. In the first of a three-part series, Fiona Sun looks at the city’s worst homes and speaks to the people living in them.

After a long night shift, security guard Leung returns to the tiny space he calls home in an old residential building in Sham Shui Po.

He has 50 sq ft in a loft space that has been subdivided into 12 units of more or less the same size, each barely enough for one person.

His space is so small that he piles boxes of personal belongings and clothes on the bed, which means he cannot stretch out fully when he sleeps. He has a sink, and a bathroom with no door, but there is no kitchen.

The windowless space is stuffy, even more so in summer. Mosquitoes keep him up on many nights, and his mattress is stained by squashed bed bugs.

“When I tell people new to the city about my living conditions, they just cannot believe it,” says Leung, 58, who asked to be identified only by his surname.

Divorced with an adult son, he moved into the unit in April last year. He had a slightly bigger unit in the same loft for about a year, but downsized when he could no longer afford the HK$3,900 (US$500) rent. Now he pays HK$2,800 a month.

There are more than 220,000 people like Leung, living in Hong Kong’s worst housing. The city has about 110,000 subdivided flats, mostly in dilapidated buildings in Kowloon and the New Territories.

Most are rented by singles or couples, but occupants also include single parents and their children, and even three-generation households.

The severe housing shortage in the city has driven people to rent tiny spaces in overcrowded flats with as many as 40 occupants.

The most notorious are “cage homes”, which are also known as “coffin homes”, where partitioned, boxlike units are stacked from floor to ceiling, separated by thin wooden boards or wire mesh.

Leung’s current accommodation reminds him of his childhood, when he and his two brothers squeezed with their parents into a subdivided flat before moving to a public rental home in Sham Shui Po.

He left home when he got married and bought his own flat. Now divorced, he left the property to his ex-wife and son.

Leung ran a logistics company in mainland China, but it went bankrupt in 2019 and he returned to Hong Kong. He was jobless until he found work as a security guard last year.

He longs to have a better place to stay, but says:“ Bad as it is, this is all I can afford for now.”

Most occupants have no choice

Hong Kong’s subdivided housing spaces, many of them windowless and plagued by hygiene and fire hazards, have been criticised for their poor living conditions.

Despite their state, the government has long adopted a policy of merely ensuring their safety rather than phasing them out, as many believe the city’s poorest need these homes.

Last July, however, the director of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, Xia Baolong, set city administrators the target of eliminating deep-seated social problems by 2049, when the People’s Republic of China celebrates the centenary of its founding.

Specifically, he demanded city leaders eradicate subdivided units and cage homes.

In what was her final policy address last October, city leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor did not refer to Xia but made housing and land supply a major focus, setting the goal of providing decent accommodation to all residents.

Her successor as chief executive, John Lee Ka-chiu, has pledged to act on housing, and made a point during his election campaign to visit poor residents of subdivided flats.

A report by the Transport and Housing Bureau in March last year said there were an estimated 110,008 subdivided units housing 226,340 people, or about 3 per cent of the city’s 7.5 million population.

It said the median area of these units was 124 sq ft, but social workers estimate that some are as small as 20 sq ft. More than 60 per cent of the units are in Kowloon, about 24 per cent are in the New Territories and the rest are on Hong Kong Island.

To protect renters, the government introduced a tenancy control bill on subdivided units last July, which was passed by the Legislative Council and took effect in January. Among other measures, it restricts rent increases when leases are renewed.

Most tenants of subdivided units say that with their meagre incomes, they have no other choice of lodging.

Unable to buy their own homes in a city with skyrocketing property prices, their best hope is to get a public rental flat. But the queue is so long that it can take a decade to get one, and most say they are forced to rent a subdivided space while waiting.

An irony of Hong Kong’s housing scene is that on a per-square-foot basis, the city’s poorest people pay rents comparable to those for private flats, or even more.

Statistics show that in April, the average monthly rent per square foot of a private flat under 430 sq ft was about HK$37 on Hong Kong Island, HK$35 in Kowloon and HK$28 in the New Territories.

For subdivided units, the median monthly rent – the midpoint between the lowest and highest rents – was HK$39 per sq ft, according to the report by the Transport and Housing Bureau.

But still people choose these homes because the overall monthly rent is still lower. The report showed that the median monthly rent for a subdivided unit was HK$4,800, much lower than for the smallest private flats.

For those in subdivided units, rent takes up about a third of their monthly household income.

The Transport and Housing Bureau report showed that these households had a median monthly income of HK$15,000 in 2020, less than half the HK$33,000 for all households in the fourth quarter of that year.

When the Society for Community Organisation (SoCO) interviewed 432 households living in tiny spaces in April last year, it found that the median monthly rent was between HK$4,500 and HK$6,500 for traditional subdivided flats – in which a standard unit is partitioned into two or more smaller spaces – HK$2,300 for tiny bed spaces, and HK$2,800 for cubicles.

SoCO found that in March last year, average monthly rents per square foot worked out to HK$104 for a bed space, HK$30 to HK$43 for a traditional subdivided flat and HK$40 for a cubicle – higher than the rate per square foot for most private homes of various sizes.

Lawrance Wong Dun-king, president of Many Wells Property Agent, says the higher rent per square foot for subdivided spaces shows the imbalance between supply and demand in Hong Kong.

“The smaller the unit is, the higher its per-square-foot rent. The result is, the poorest pay the highest rent,” he says.

‘Waiting for death’

For the past seven years, Xing Aizhen, 46, and her two sons from her first marriage, aged 20 and 15, have shared a 100 sq ft space in a Mong Kok flat.

Originally from Hainan province, she came to the city with her sons in 2015 after marrying again, but her second marriage to a Hongkonger ended in divorce too.

Earning about HK$10,000 a month as a part-time waitress, she says she cannot afford anything better than the subdivided unit, which costs HK$3,900 a month.

Her two sons share a bunk bed while Xing sleeps on a single bed. Their bathroom and kitchen practically share the same space, and she can smell the stench of the toilet while preparing food.

With only two small windows, the place is so poorly ventilated that stir-frying food leaves a strong, greasy odour. She only boils or steams their meals.

“The place is just too small for the three of us,” she says, adding that her older son often complains about the arrangement.

She says the space seemed even smaller during the coronavirus pandemic, when the three of them stayed at home. Her older son took online vocational cooking courses, and her younger son, in secondary school, also had online classes. She has been staying home more too, as her employer cut her working hours and income.

After waiting five years for a public rental flat, Xing says she hopes to provide a bigger place with better living conditions for her sons.

“A good place to live is important for us to lead a stable and secure life,” she says.

For many like her, public rental housing offers the only hope, but such flats are hard to come by.

As of March this year, there were about 147,500 general applications for public rental housing from families and single elderly people who had priority, with an average waiting time of 6.1 years.

Further back in the queue were about 97,700 non-elderly single applicants, many of whom have been waiting for decades.

SoCO deputy director Sze Lai-shan says that when it comes to inadequate accommodation in Hong Kong, the “coffin homes” are the worst of all.

“Some elderly people describe their lives in cage homes as ‘waiting for death’,” she says.

Hongkonger Tsang Shiu-tung, 51, says he sees “no light at the end of the tunnel”, having been in the queue for public rental housing for 16 years.

He lives in one of 18 coffin-like bed spaces separated by wooden boards in a flat in a dilapidated tenement building in Yau Ma Tei.

“I live like an animal in a cage,” he says.

Divorced with no children, he moved into the place in May last year and pays a monthly rent of HK$1,500. The pandemic has left the part-time supermarket porter with a reduced income of less than HK$10,000 a month.

The tiny compartments, each marked with a number, are stacked into two levels. The 18 male tenants, aged from their 40s to their 80s, share two bathrooms, only one of which has a shower. There is no kitchen.

The environment is hellish, Tsang says. His upper-level bed space is so narrow that he can barely stretch out fully or sit upright without hitting the wooden partition, only to have the man in the bunk below kick upwards to signal his irritation.

Some of the men stay up late, others smoke indoors and the pungent smell of cigarettes lingers. Tsang draws the door of his compartment, but that does little to block the noise or smoke, and only makes it stuffier inside.

There have been times when he resorted to sleeping rough in parks just to get away.

“I want to escape from this place, where I feel so helpless,” he says. “All I want is a safe place to live.”