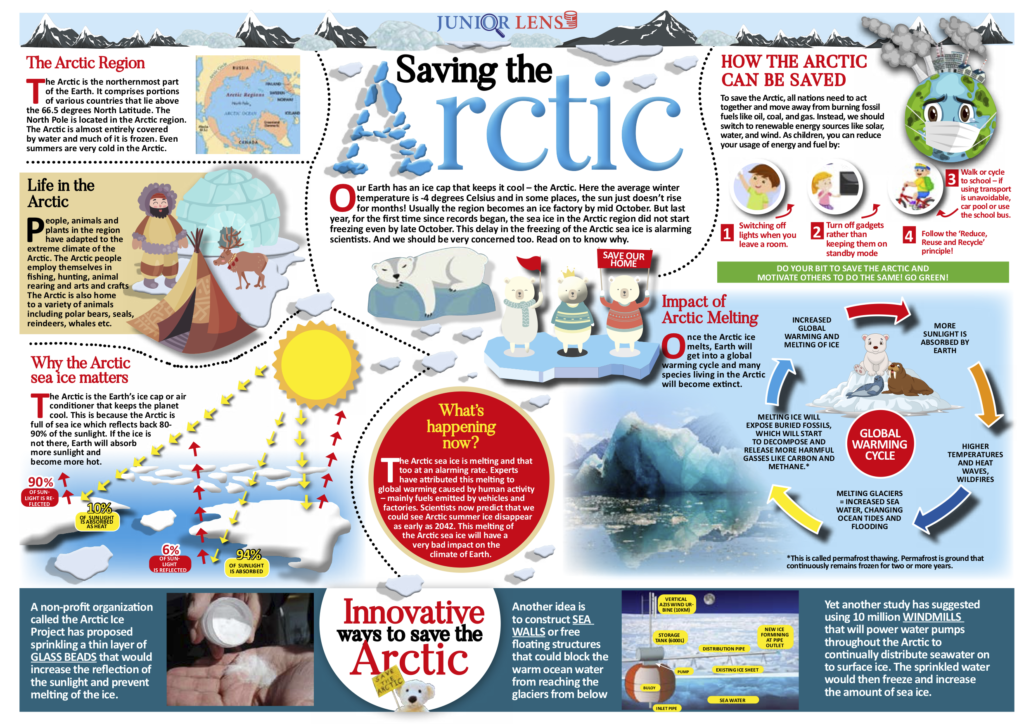

Aotearoa New Zealand’s braided rivers are internationally significant, but they’ve been systematically strangled, and in some cases, have left behind zombie rivers. As climate change threatens to make the problems worse, some academics and scientists are re-imagining what it means to live with rivers.

By the time it started raining high in the Southern Alps, it was already too late for those downstream.

It had been raining for several days in the headwaters of the Rangitata River, between Christchurch and Timaru, by the evening of December 6, 2019. A sudden downpour overnight brought the highest river levels observed in two decades, and made it inevitable the river would burst its seams. The question was where.

Like other braided rivers in the region, the Rangitata has been heavily modified. Roads, stop banks, and farmland flank its edges; an enormous line of ponds stapled to its side, designed to capture flood waters for irrigation, resemble an artificial second river.

Before human settlement, the river would have simply flooded, forging a new path for itself. But now it was barricaded with stop banks, its floodplain populated by people with lives and property. The river had been narrowed, giving the kinetic energy of the floodwaters little opportunity to disperse; it could only build strength as it barrelled down the plains.

When the floodwaters came, they breached the entrance to what used to be the South Branch of the river.

Long ago, the Rangitata river split in two. The Southern Branch has since dried up, and is now covered in irrigated pasture (the land between the two branches was Rangitata Island, a name which remains).

The floods revived the dead southern branch, which at its peak had more water flowing down it than the main river itself. Some of that water itself broke out, flooding state highway one and cutting off the bottom part of the country for several days. At least two more breaches in the main river added to the flooding.

From the ground, it would have seemed like chaos; floods of water rampaging over the plains, damaging anything in its path. But from above, a different picture was emerging. Environment Canterbury (ECan) staff were photographing the floods from the air, later stitching together the images to create a mosaic of the event.

It showed the floodwaters were following a predetermined pattern. The flood was itself a river, with twists and braids and tributaries, much like the Rangitata itself.

A zombie river, long ago buried beneath asphalt and housing and irrigators, had been revived.

Over thousands of years, the braided rivers of the Canterbury plains painstakingly sketched the landscape they now occupy.

There are more than 150 braided rivers in Aotearoa New Zealand, almost all of which are in the South Island. Their floodplains alone span around 250,000ha, more than double the size of Auckland City.

Most notable are the braided rivers that formed the Canterbury Plains, the largest area of flat land in the country: The Rakaia, the Rangitata, the Waimakariri, the Waitaki, the Ashley/Rakahuri, and the Waiau.

It is a privileged responsibility, given how few of the world’s rivers are braided. Most rivers, globally speaking, are meandering: They have a single channel, filled with water, that goes from one place to another. Think of the Waikato, the Clutha, the Avon.

Braided rivers are complicated, dynamic, destructive; they are three-dimensional, in that water also flows beneath the river, popping up as springs and wetlands which are periodically destroyed and recreated, as if the braided river system is creating its own universe.

Some say braided rivers are better seen as four-dimensional; they move across time, existing in different shapes and forms on the scale of millennia. Where a river ends now may be dozens of kilometres from where it ended centuries ago.

Several specific factors are required for a river to become braided. One is gradient: They must start at high altitude, tumbling steeply to sea-level over a short distance. They also need a constant supply of rock and sediment, which usually comes from young, rapidly eroding mountain ranges like the Southern Alps which are large enough to create their own weather.

Rain and snow strips the mountains of rock and sediment, as do the massive glaciers that emerge and recede over long time periods, cutting against the mountains, leaving more rock and sediment, all of which is swept downstream towards the coast.

Much of this rock settles on the river beds, forming shingle islands between small, twisting water channels. When it floods, the streams merge into a single channel, carrying the rock and sediment out to sea in a torrent, which is swept back towards the land by the tides to build beaches and protect against coastal flooding.

When the floodwaters recede, the river may have redesigned itself; shifted its islands, created new braids, destroyed old ones. Then the process begins anew.

Central to this process is flooding.

All rivers flood in the right conditions, but for braided rivers, floods are a defining aspect of their physical function.

Braided rivers are more complicated. They are incredibly wide, and contain a series of narrow channels that weave around mounds of rock. Where the river begins and ends is not always clear; they cut into the landscape, forming terraces, which can be indistinguishable from a traditional riverbank.

“The problem with braided rivers, like any other river, is they periodically break their banks,” says Sonny Whitelaw, manager of braided river conservation group BRaid (Braided River aid).

“The natural reaction is to say we’re going to put up these barricades to control the river and prevent them from flooding. And of course, the more you confine it, the more you risk flooding, because you’re trying to carry the same amount of water in a much narrower channel.”

We sometimes think of river flooding as abnormal; a departure from regular order, a river’s failure to fulfil its implied promise to neatly channel water from one place to another.

But flooding is a feature, not a bug. Floods create and destroy new habitat, and carry sediment from the mountains to the coasts. The tension comes when people, property, and infrastructure are put in the way, justifying further measures to control the river, which can themselves make the problem worse.

That was evident during the catastrophic Canterbury floods early this month, which caused widespread damage, mostly from braided river flooding.

For many, it was a lucky escape. The flooding was worst in the smaller braided rivers, namely the Ashburton and the Ashley/Rakahuri, largely because their headwaters are in the foothills, which are more influenced by northeasterly rain (the larger braided rivers, with headwaters higher in the mountains, are more influenced by traditional westerly rain).

Some, of course, were not so lucky. Lives and property were damaged; the rivers, unable to be controlled, revived their dead channels, indifferent to what had been built in the interim.

It shows when a braided river floods, even smaller ones, the consequences can be severe. It highlights a fundamental tension: Can humans and braided rivers peacefully co-exist, particularly given the expected impacts of the climate crisis, which, in some ways, will make the rivers more powerful than ever?

***

When the Waimakariri River north of Christchurch spilled its banks in 1868, it caused significant alarm in the city and its surrounds.

Water flooded much of Christchurch, including Cathedral Square. But the worst damage was done in Kaiapoi, on the northern bank of the river.

As detailed by The Press: “Kaiapoi, in spite of all the protective works and cuttings constructed by the inhabitants in the hope of averting the attacks of their dreaded enemy, has, we fear, suffered terribly.”

The language used by the newspaper was instructive.

To some, the Waimakariri is a tupuna, a taonga, a provider of mahinga kai. To the settlers, it was a “dreaded enemy”, something to be protected from.

The settlers were not living with the river; they were at war with it. In some ways, they still are.

Communities have long been built along rivers. Floodplains are fertile, flat, and easy to develop; the rivers themselves can be harnessed as machines for economic growth.

“The first civilisations on our planet emerged in places like Mesopotamia – ‘between the rivers’ – so it’s not a new thing,” says Professor Gary Brierley, a river scientist and chair of physical geography at the University of Auckland.

“And just like those ancient civilisations fell over because practices were unsustainable, what we’re doing is unsustainable.”

The problems have become more pronounced as society has moved closer and closer to the rivers, emboldened by the idea they can be controlled.

We can build stop banks to prevent flooding, or capture floodwaters when they get too high; we can funnel rivers down a particular path, take the gravel out of the riverbed, stuff streams and tributaries back into the main channel when they break out.

But some of those practices have undoubtedly made the problem worse, and the costs have become increasingly hard to justify.

In Christchurch, efforts to protect the city from the Waimakariri River are costly. The most recent upgrade of the stop bank system cost around $40m. In 2020, insurers nationwide paid out nearly $170m in flooding-related damage (figures which include surface flooding from rain).

Between 1990 and 2012, around 12,000ha of river margin land in Canterbury was claimed by farmers, an analysis by ECan found. Some of this development has been in the riverbed itself, and has put productive land in the path of river floods and erosion.

Braided rivers have been tapped for water to irrigate farmland, and dammed to generate electricity. The flatlands cleared by the rivers have made way for quarries, housing, landfills and other infrastructure, further justifying engineering solutions to protect against floods.

We drive our cars through the gravel braids to fish introduced species like salmon and trout. Introduced predators feast on threatened native species that live in braided habitat, and exotic weeds and trees choke the river margins, further disrupting the river’s natural flow.

To manage flooding and use land for economic development, braided rivers have been narrowed significantly, which makes them more hydraulically efficient: They carry water faster, with more energy. At the same time, wetlands – a crucial buffer against flooding – have been systematically removed.

With climate change, heavy rainfall events are expected to become more severe, particularly in the headwaters of the major braided rivers. At the same time, drier conditions on the plains could increase reliance on water, particularly for farms, moving us closer to the rivers.

“We’ve got all these factors conspiring to make things more difficult for us, and where we’re at now is only going to be accentuated into the future unless we turn some of these things around,” Brierley says.

“We wanted the convenience of rivers, but at the same time, we wanted to turn our backs to them in terms of a lot of the practices that we undertook.”

Dead channels south of the Waimakariri River show its former path.

It has prompted a new way of thinking among some river scientists. As the relationship between rivers and humanity becomes more fraught, how do we co-exist?

Earlier this year, a group of New Zealand academics and scientists co-authored a piece arguing that rivers were being “strangled”, and actions were required to undo the damage.

It is a concept gaining favour internationally. Experts in the United Kingdom recently argued letting rivers run wild could significantly reduce flooding; In the United States, ageing dams are being systematically dismantled to allow rivers to flow more freely. Attempts to restore the Old Rhine River in Europe by allowing its natural functions to return have had promising results.

There are many names for this practice; rewilding, reanimation, redynamisation, integrated river management, decolonisation. In the simplest terms, it’s letting a river be a river.

It’s an idea that has gained favour in Aotearoa New Zealand over the last five years. It’s not limited to water scientists; a cross-disciplinary group including engineers, ecologists, and geomorphologists have made the argument for letting rivers be rivers.

It can cause questioning of standard practices within their respective disciplines

“There is often a tension between engineering and science,” says Dr Heide Friedrich,✓ an associate professor of engineering at the University of Auckland.

“In engineering, we want to put everything in boxes – everything needs to go a certain way. Whereas in science, we understand complexity, holistic assessment, and so on.”

Engineers have played a significant role in river management. By one estimate, stop banks in Aotearoa New Zealand span around 5000km, more than double the length of the country itself. They protect many billions of dollars of assets – not to mention lives – from floods.

But the cost is not only financial. Some of the environmental consequences have not been well understood.

After modest rainfall near Franz Josef in 2016, the Waiho River breached a stopbank and took out a hotel. A few years later, the same river flooded again, destroying a bridge which cost $6m to replace.

It comes after a long period of trying to confine the river, but sediment build-up on the river-bed has increased water levels. The solution has been to build the stop banks higher, which is not financially sustainable. One option is to let the river reclaim its floodplain, which has been converted to pasture, or to move Franz Josef township entirely.

Another example, Friedrich says, is floodwater harvesting – taking water from floods that would otherwse flow out to sea to store for irrigation. It is used on the Rangitata River, where floodwaters are stored in enormous ponds beside the river.

While it may seem sensible, floods appear to have a significant role in transferring sediment, both out to sea and on the river-bed itself. Once a sediment regime is altered, it can take decades to reverse, and the impacts can be significant; sediment provides shelter to aquatic life, and builds up coastlines to protect against erosion, a growing problem with climate change.

It’s the sort of problem engineers need to grapple with, Friedrich says. Conventional systems don’t always work.

“In the past, often engineers did a lot of studies, came up with solutions and implemented them. But especially when it comes to water environments, we see there are a lot of unintended consequences,” she says.

“We need to ask critical questions of water processes before we sign off on an engineering solution. Just because there could be an engineering solution doesn’t mean we should use it.”

In one sense, the problem is simple to describe. Humans, particularly since colonial settlement, have operated under the assumption rivers are static, a strategic error that becomes harder to reverse the more time goes on.

“I think the first step is recognising we have created a problem,” says Dr Dan Hikuroa, an Earth systems scientist and a senior lecturer in Māori studies at the University of Auckland.

“A river has been a river mai rānō, since forever. We’ve created a problem by building on its banks or nearby, restricting it.”

Hikuroa advocates for a mixture of science and Mātauranga.

River management in Aotearoa New Zealand has been pre-occupied with a river’s component parts; setting acceptable levels for the likes of nitrogen, phosphorus and E. coli, each of which can be independently measured and controlled.

Much of the public (and political) debate about freshwater has centred on “swimmability” – whether rivers can fulfil the recreational needs of humans.

For some river scientists, mātauranga has clarified questions science has been unable to resolve. What if, instead of seeing a river as a machine to be controlled, something that can be deconstructed, we recognised its mauri and accepted it has a fundamental right to be a river?

The two forms of knowledge are not inherently in conflict, and can be complementary. It is an idea, appropriately, informed by the structure of a braided river itself: He awa whiria, two channels weaving and twisting, creating something stronger.

“If you can imagine two strands of knowledge, when you have woven them, they’ll be stronger than those individual strands were on their own,” Hikuroa says.

“Each maintains its own integrity within that new thing, whatever it is.

“It’s not just understanding the role of nitrogen, or phosphorus, or E. coli – Those are discrete pieces of information that are valuable and valid on their own, but make most sense when considered as part of that holistic system. It’s when we go right down on those small parts, as opposed to looking at the whole system, where things can go awry.”

Water storage ponds on the banks of the Rangitata river.

File generic drone aerial

It is a view that has already moved beyond academia.

Te Awa Tupua, the law granting the Whanganui river legal personhood, recognises such values explicitly: “Te Awa Tupua is an indivisible and living whole, comprising the Whanganui River from the mountains to the sea, incorporating all its physical and metaphysical elements,” the law says.

Similar wording is contained in Te Mana o Te Wai, the concept underlying the Government’s freshwater reforms in 2020: In its hierarchy of obligations, the health and well-being of the water comes first, ahead of human and economic needs.

A few years ago, at the Christchurch District Court, a farmer was charged with an unusual offence –building a wall in the Selwyn River.

The Selwyn River is braided over some of its length. Much of its observable span is dry, meaning the course of the river channel – particularly where it starts and ends – can be hard to determine.

What seemed like a standard prosecution would come to have significant ramifications.

The farmer acknowledged building the structure – a bund to protect his land from flooding – without permission, but disputed the claim it was in the riverbed, which would come with a harsher punishment.

He argued the wall was in the floodplain, not the riverbed itself. He was found guilty, but appealed.

The High Court sided with the farmer, as did the Court of Appeal.

It speaks to the confusing way in which rivers are defined. Under the Resource Management Act (RMA), a riverbed is: “[T]he space which the waters of the river cover at its fullest flow without overtopping its banks”.

Neither “fullest flow” nor “banks” are defined. So what does it mean?

In bringing the prosecution, ECan had interpreted it to mean where the river would flow in a one-in-20 or one-in-50 year flooding event, an argument it had successfully used before. Under this definition, a river’s floodplains would be considered part of the river.

The High Court, however, disagreed. It cited a 1905 case regarding the Hutt River, which defined a river in relation to normal seasonal flow. Under this definition, a river does not include its floodplain; it is a static channel. The court’s interpretation stands, radically changing the definition of some riverbed land.

The biggest consequences are for braided rivers, which are, technically speaking, mostly floodplain, and are clearly not static.

The regular flow of water – the channel – is a minor part of a braided river; it’s only after heavy rain, when the water swells and erodes the river’s banks, changing the river’s course, that the river operates how it should.

As other countries move further towards unstrangling their rivers, legally speaking, New Zealand’s are more strangled than ever (the Government has announced an overhaul of the RMA, but it’s unclear if the definition of a riverbed will change).

“Under the RMA, the definition of a braided river isn’t a braided river – it goes right back to this colonial attitude towards a river being just a channel,” says Sonny Whitelaw, of BRaid.

It’s part of a broader problem, she says. How do you define the position of something that constantly moves?

“The question is, what exactly is a braided river? Are we looking at a braided river as it was yesterday, or last year, or last century, or before people arrived?

“This is a conundrum we’ve got. The damn things don’t conveniently stay in one nice to find place – they’re prone, at a moment’s notice, to just sort of pickup and change location.”

If you’ve flown into Christchurch, you may have seen how this happens. Land around the braided rivers are covered in stretch marks.

They are dead channels and streams, left by the Waimakariri River as it shifted north to its current position (thousands of years earlier, the river likely flowed near Te Waihora, south of the city.)

With no intervention, the river would likely shift back, over a long enough time period. With the country’s second-largest city now in the way, protected by 100km of stop banks, that is unlikely to happen.

It is an issue across the lower stretches of every braided river, and the defining challenge for the river reanimation movement.

“We have already encroached on them too much, whether it’s from agriculture, or weeds, or our bridges and roads and wastewater treatment plants, cities, you name it,” Whitelaw says.

“I feel like I struggle with this every day. We either choose to take a holistic view and say okay, we need to withdraw, we need to enable the rivers to act more like living rivers rather than zombie rivers.

“But we need to know that we’re going to sacrifice things to do that, and the question is, who pays for it?”

Mātaraunga shows people can learn to live with rivers. When a flood damaged much of Mātata township in 2005, among the few buildings that weren’t damaged were marae.

The reason was a pūrākau, a narrative applied to the landscape. The river was said to house a taniwha in the form of a lizard, its tail flicking side to side, a sign that people should be cautious.

The story contains a basic geomorphological fact; the lower channel of the river laterally shifts after floods.

It is one reason for optimism. This is a problem that predates everyone alive today; Perhaps two forms of knowledge, braided, can help ease tensions in the long-standing war between humans and rivers.

“It comes from a way of knowing and being that sees you as part of that system, that sees waterways as ancestors, as tupuna, that says we would prefer to treat them like taonga, not as toilets,” Dan Hikuroa says about the move to reanimate rivers.

“That kind of thinking, combined with some cutting edge technical tools where we can be measuring real time E. Coli, nutrient loads, silt loads, rainfall modelling… I think there’s an approach where we can see rivers as more than just a bed, banks, and the water in it, and that’s definitely the way forward for us.”

For Gary Brierley, the river scientist, answers to some pressing questions have been there all along. It’s now time to put the solutions in place.

“A Mataraunga Māori lens is second nature to many groups across the country, and it’s frankly, the direction that we need to be going,” he says.

“To me, it’s an incredible paradox – We have a good idea from science as to where we want to be, and because of the Treaty obligations, if there’s any part of the world where it should be pretty easy to do this, to get on with it, it’s here. And yet we have fallen behind the rest of the world.”

This story, published by Stuff, has been shared as part of World News Day 2021, a global campaign to highlight the critical role of fact-based journalism in providing trustworthy news and information in service of humanity. #JournalismMatters.