To mark World News Day on September 28, 2022, the World News Day campaign is sharing stories that have had a significant social impact. This particular story by Fiona Sun (Edited by Emily Tsang and Alan John) — with visual storytelling by Adolfo Arranz, Marcelo Duhalde, Kaliz Lee, Han Huang and Dennis Wong — was shared by the South China Morning Post (Hong Kong).

In the last of a three-part series on Hong Kong’s subdivided flats, Fiona Sun looks at the alternatives for tenants, their prospects for better accommodation, and what the government needs to do to achieve Beijing’s target of getting rid of such housing by 2049.

Cindy Lu finally put her days of living in a tiny subdivided space behind her, after waiting 10 long years.

The housewife, 37, moved into a public rental flat in Kwai Shing East last October with her husband, 39, two daughters aged 14 and 11, and two-year-old son.

Their 450 sq ft flat has a living room and three bedrooms, and the monthly rent is about HK$2,500 (US$320).

“ Finally I don’t have to worry about rats and cockroaches or the ceiling leaking on rainy days. Nor need I fear rent increases or being kicked out at any time,” she says.

Before this, the family paid HK$4,200 a month to squeeze into a 100 sq ft subdivided unit in Kwai Chung. It seemed even smaller during the coronavirus pandemic, when all five were at home.

The family had only known living in similar tiny spaces, because they could not afford better on her husband’s income of about HK$10,000 a month as a construction worker.

Public rental housing was their only hope of better living conditions and they applied in 2011, only to wait a decade before the good news finally arrived last year.

“The wait and struggle seemed endless,” Lu says. “But now I’m looking forward to a stable and secure life. It finally feels like a home.”

More than 220,000 people live in about 110,000 subdivided units, Hong Kong’s smallest and most substandard housing, and many long for better accommodation.

According to a report released by the Transport and Housing Bureau in March last year, nearly half of households in subdivided flats had applied for public rental housing.

A survey by the Hong Kong Council of Social Service between June 2020 and January last year found that about seven in 10 of the 2,108 respondents living in subdivided flats had no idea how long they would remain in such housing. The rest expected to stay for about four years on average.

Long wait to move out

Social workers and experts say that skyrocketing private home prices and rents, the severe shortage of affordable public housing, and insufficient government and social support have left many unable to get out of substandard living conditions.

For many, public rental housing is their only shot at anything better, but the wait can be agonisingly long.

Hong Kong had 844,078 public rental flats at the end of March this year, housing about 2.2 million people.

As of March this year, there were about 147,500 general applications for public rental housing from family and elderly one-person applicants, with an average waiting time of 6.1 years.

Further back in the queue were another 97,700 non-elderly one-person applicants, many of whom have been waiting decades.

“I have grown older in these tiny units. I will probably die in one of them,” says Jane*, 47, who has lived in subdivided units for about 30 years.

The single woman, a clerk, left her parents’ public rental flat at 18 and has moved about eight times over the years, whenever landlords sold the property or raised the rent.

On her salary of HK$10,000 a month, this is all she can afford, even as rents have crept up and her living space has shrunk. She started out paying HK$2,000 a month for a 200 sq ft unit, but now pays HK$4,200 for less than 100 sq ft in Sham Shui Po.

Her current place has room for only a single bed, table and fridge, but she worries her landlord may raise the rent and she will have to move again.

Jane applied for a public rental flat in 2005 but has no idea if one will ever come her way. The endless waiting has left her feeling helpless and depressed.

New moves to ease housing woes

Social workers have long urged the authorities to build more public rental flats to meet the demand.

“Some residents have waited so long that they grew old and gave up, waiting for death in their subdivided units,” says Sze Lai-shan, deputy director of the Society for Community Organisation (SoCO).

Outgoing Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor said last October that the government had identified about 350 hectares to build about 330,000 public housing units over the next decade, exceeding demand.

She said another 5,000 units would be added to the overall supply of transitional housing, making a total of 20,000 units in coming years for people living in poor conditions while waiting for public rental flats.

As of May, there were 4,484 transitional housing units with about 6,000 occupants.

The government has also subsidised NGOs to rent suitable hotels and guest houses to use as transitional housing. As of April, it had approved five NGOs to provide 730 units and about 450 have already been occupied by about 570 people.

SoCO has provided about 300 transitional housing units, including hotel rooms and private flats, for about 700 people, who pay HK$2,000 to HK$6,000 a month and can remain for up to three years.

Sze says such units – clean, with windows and are under good management – are still in too short supply and there are thousands on the waiting list.

Among the first to move into SoCO’s transitional housing was Steffen Lee Kar-chow, 72, who settled into a 100 sq ft hostel unit in Mong Kok last August at a monthly rent of HK$2,500.

He has a double bed and cupboard, but no table. The bathroom is small but clean. Without a kitchen, he has to buy takeaway food and eat over his suitcase. The only window opens to a podium that stinks of sewage.

“It is much better than the place where I used to live,” says Lee, who has four children from a past relationship but has no contact with them or their mother.

The retired underground surveyor used to pay HK$1,500 a month for a bed space in a flat with a dozen other male tenants who shared one toilet.

He had nothing but a bed and, for privacy, he had to hang a piece of cloth around his tiny space. He wore earplugs when he wanted to shut out the sounds around him.

Happy with his SoCO unit for now, he hopes he will get a public rental flat eventually. He applied for one last year, but was told he did not qualify because his savings exceeded the limit.

He will apply again when his savings run out.

More efforts to protect tenants

A new tenancy control bill passed by the Legislative Council last year took effect in January, which, among others, restricts rental hikes and utilities charges.

But tenants and concern groups said not much has improved, as many occupants were still overcharged for water and electricity, and some landlords resorted to oral agreements instead of signing a written contract with tenants to bypass the regulations.

They also criticised the authorities for failing to enforce the law and intervene in cases where the rules had been breached.

Other schemes by the administration aim to improve the living conditions of those waiting for public rental flats.

The Cash Allowance Trial Scheme, launched in June last year, offers cash allowances of HK$1,300 to HK$3,900 a month for households who have waited for public rental housing for more than three years. About 90,000 households are expected to benefit.

The Community Care Fund started a two-year programme in June 2020 to provide a one-off subsidy for low-income households in subdivided units. The subsidy, with a ceiling of HK$8,500 to HK$13,000 depending on household size, can be used to make minor improvements and repairs, buy furniture and household goods, or engage pest control services.

NGOs and other social institutions also offer help.

The Caritas Community Development Service runs activities for households of subdivided flats on Kim Shin Lane in Sham Shui Po and has set up a platform for them to give their views and approach government agencies for help.

Wong Siu-wai, its senior social work supervisor, says these efforts have encouraged households to clean the common areas in and around their flats to improve their living environment.

“Although they still live in subdivided units, they now contribute to the community, which helps improve their well-being,” she says.

The Hong Kong Sheng Kung Hui Lady MacLehose Centre has a 100 sq ft kitchen, a washing machine and clothes dryer at its Kwai Chung centre for residents of subdivided units in the area to use. About 100 residents use these facilities each month.

The centre also provides residents with legal advice and help with moving and home maintenance.

Worries, optimism over 2049 target

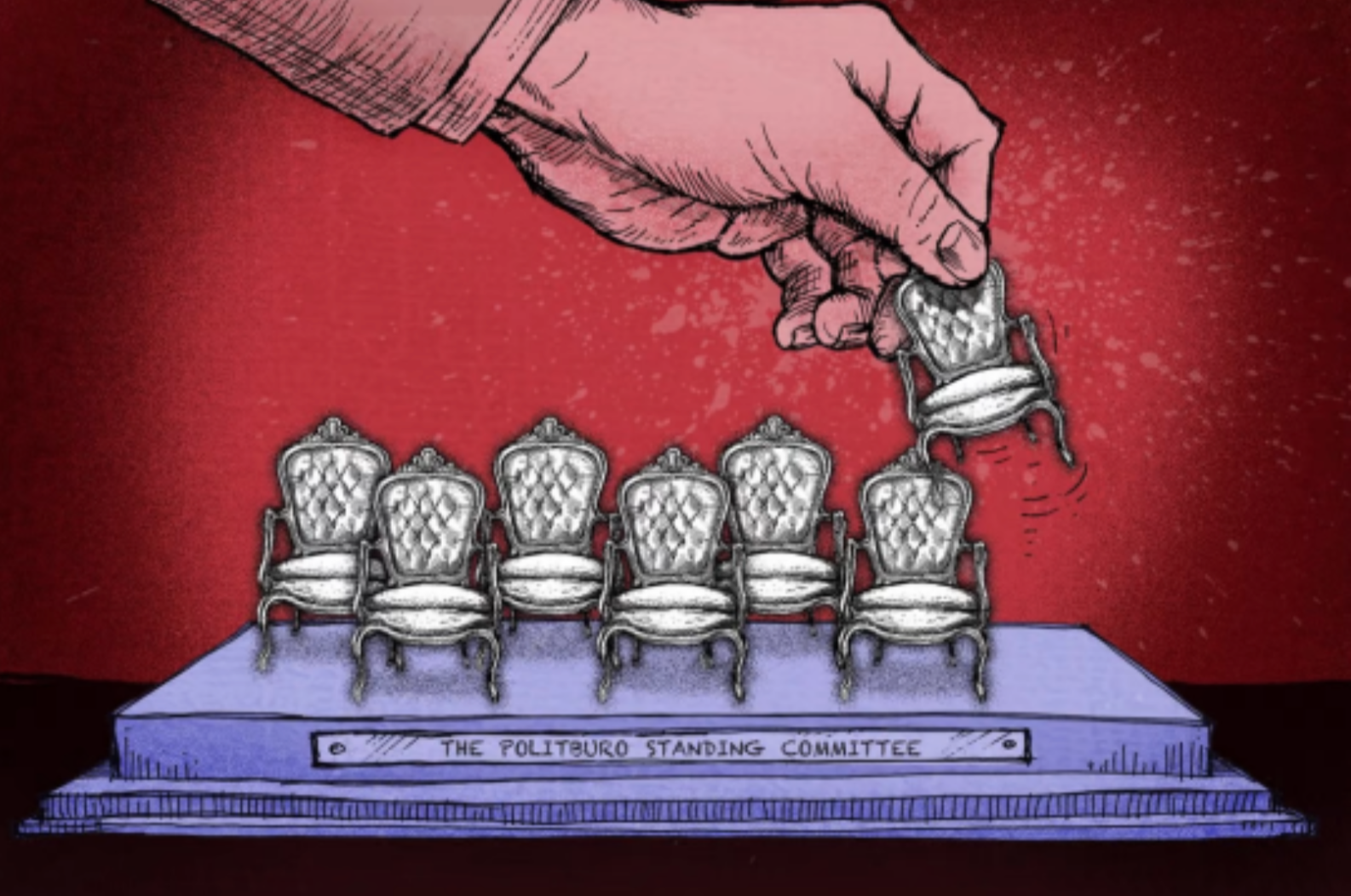

While these various schemes are welcome, the main question is whether Hong Kong can meet Beijing’s target to get rid of subdivided flats and “cage homes” by 2049.

This was a goal set last July by the director of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, Xia Baolong, for the city’s administrators to achieve by 2049, when the People’s Republic of China celebrates the centenary of its founding.

Peace Wong Wo-ping, chief officer of policy research and advocacy of the Hong Kong Council of Social Service, a federation of non-government social service agencies, says the existence of subdivided units reflects the problems of the city’s housing market, including the shortage of supply, lack of regulation and the inability of low-income people to meet their living needs.

He says it will take a determined effort by the city authorities to deal with the issue of subdivided units.

“If it is successfully achieved, all residents, both rich and poor, will reach a minimum housing standard,” he says.

But Tang Po-shan, convenor of the Hong Kong Subdivided Flats Concerning Platform, a community organisation of social workers and scholars, warns that simply eliminating subdivided flats could give rise to other forms of inadequate housing with poor living conditions.

He says the government should not only get rid of such designs, but also resettle the households.

“The key should be improving the living environment and quality of the residents,” he says.

Tang adds that many tenants are indifferent to the government’s target almost three decades from now, and some are worried about what choice they will have if these cheap units are wiped out.

He says:“ They are asking, ‘Will my living conditions truly improve after subdivided units disappear?’”

Professor Yau Yung, of Lingnan University’s department of sociology and social policy, says the key to achieving the 2049 target without driving households to other forms of inadequate housing is the government’s ability to increase the supply of public rental flats significantly.

He says the current average waiting time is too long and should be reduced gradually, to at least four years initially.

The government should also consider legislation to ban more subdivided units coming on the market.

Yau points out that this is not the first attempt to wipe out these tiny units. Former city leader Leung Chun-ying’s administration also tried to do so, but found it too difficult to rehouse affected residents because there were not enough homes they could afford.

“The 2049 target is a good thing for Hong Kong,” Yau says. “It can be achieved, but it depends on what the government will do from now on.”

Dr Lawrence Poon Wing-cheung, a senior lecturer at the building science and technology division of City University, says the city’s political conflicts left many government policies in limbo over the years.

He urges the government to take advantage of the current stable social environment to move forward quickly with land-related policies to increase housing supply.

A former member of the Town Planning Board, he suggests exploring land reclamation possibilities, changing the land use of some areas, and raising plot ratios – which fix the built-up area on a site – to build more homes.

Optimistic that the target can be achieved before 2049, he says:

“In a city with a highly developed economy like Hong Kong, it is unacceptable to have these subdivided units, which must be wiped out.”

*Name changed at interviewee’s request.