To mark World News Day on September 28, 2022, the World News Day campaign is sharing stories that have had a significant social impact. This particular story was shared by Organización Editorial Mexicana (OEM).

En la ciudad nadie quiere hablar de lo ocurrido en 2011 y todavía persiste el temor.

ALLENDE, Coahuila.- Sólo fincas abandonadas y destruidas y el silencio autoimpuesto de los habitantes de Allende queda luego de la masacre perpetrada en esta ciudad del norte de México hace ya más de una década por Los Zetas, en una venganza contra un soplón.

En una redada, la DEA decomisó más de 800 mil dólares en efectivo que iban ocultos en un tanque de un vehículo conducido por uno de los miembros del cártel, quien identificó a su jefe como José Vázquez Jr., alias El Diablo.

Vázquez Jr. era el distribuidor de cocaína más grande de Los Zetas en Texas, por lo que los agentes estadounidenses lo vieron como una gran oportunidad para llegar a los líderes del cártel y capturarlos.

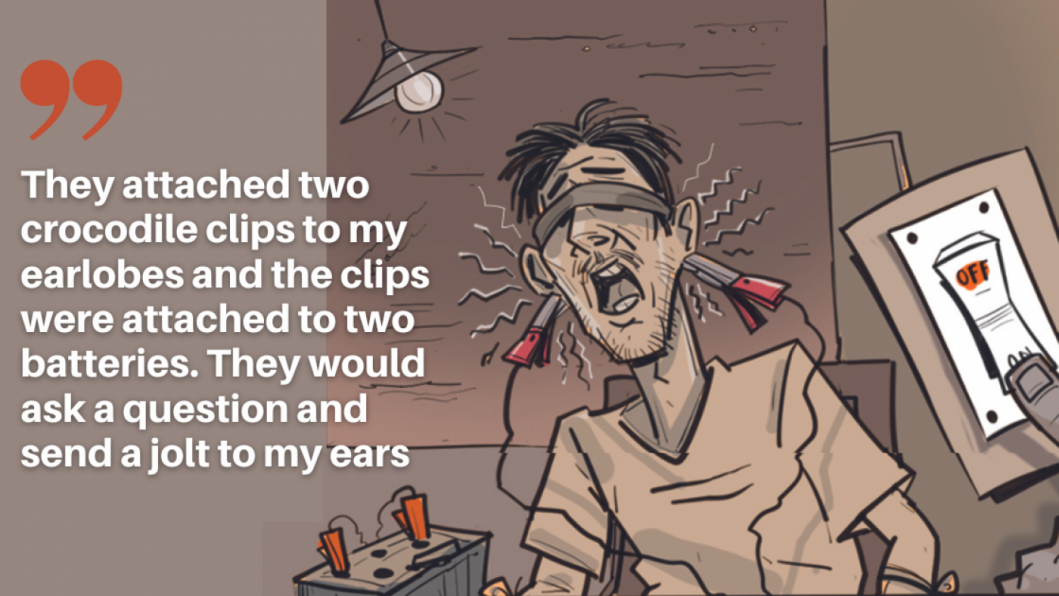

La DEA presionó a El Diablo con la amenaza de meter a la cárcel a su esposa y su mamá si éste no les proporcionaba información de los Treviño Morales. Éste aceptó y convenció a Héctor Moreno, otro miembro de Los Zetas, de entregarle los números de rastreo de los celulares de sus jefes.

Moreno se encargaba de comprar celulares nuevos cada 15 días a los Treviño Morales para evitar que sus comunicaciones fueran interceptadas.

El Diablo entregó a la DEA la información de los celulares y estos compartieron los datos con una unidad de la Policía Federal de México para que los rastreara y detuviera. Sin embargo, los agentes mexicanos informaron al cártel sobre la filtración de información, lo que desató la rabia de los líderes. El cártel de inmediato supuso que Héctor Moreno y José Luis Garza habían sido los “soplones”.

Garza era de Allende y formaba parte de una familia adinerada que se dedicaba a la ganadería y minería de carbón. Los hermanos Treviño Morales planearon la venganza en contra de sus delatores, enfocando primero su artillería en contra de la familia Garza y cualquiera que tuviera algún vínculo con ella.

Allende se encuentra a 383 kilómetros de Saltillo, la capital de Coahuila, al norte de México, y a 649 kilómetros de Torreón. Llegar ahí no es sencillo. En la señalética que está en la entrada del municipio precisa que, según el Censo del Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística, en el 2020 había 42 mil 756 habitantes. El letrero, que todavía muestra los balazos de los encontronazos entre grupos delictivos y autoridades, está a menos de veinte metros de un retén militar y a 100 metros del cuartel de la Policía Civil de Coahuila.

Así fue que el viernes 18 de marzo decenas de criminales llegaron al poblado, localizaron las propiedades de los Garza y secuestraron a todo aquel que estaba en su interior.

Para en la noche se podían ver las llamaradas a lo lejos que salían de los ranchos. Los sicarios no hicieron distinción: hombres y mujeres, ancianos y niños, todo aquel con apellido Garza y que tuviera relación con la familia fueron desaparecidos y asesinados.

Incluso desaparecieron estudiantes, deportistas, profesionistas y pobladores que nada tenían que ver con los Garza y su único error fue haber estado esa noche en la calle.

La mañana del sábado 19, retroexcavadoras comenzaron a demoler las propiedades de los Garza: bodegas, casas, negocios y quintas de descanso.

Luego, los criminales incitaron a los pobladores a que las saquearan. Familias enteras entraron a las fincas por televisores, electrodomésticos, muebles y hasta el cableado. No quedó nada.

LA INACCIÓN

Del 18 al 22 de marzo en Allende y Piedras Negras se recibieron en el Sistema de Emergencias 089 un total de mil 451 reportes de auxilio que nadie atendió.

De acuerdo con la Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos, la policía municipal participó activamente en la desaparición de personas según la recomendación 10-VG/2018.

Después de consumar la masacre, el pueblo enteró calló por años. Aunque era un secreto a voces, nadie hizo nada. Ni autoridades ni fuerzas de seguridad se atrevieron a enfrentar al que era entonces el cártel más poderoso y sanguinario del país, pese a que algunos familiares de las víctimas habían interpuesto denuncias en la agencia del Ministerio Público en Piedras Negras.

En la mayoría de los casos de desaparición los familiares no denunciaron por temor de ser rastreados y asesinados y fue hasta principios de 2014 que se dio a conocer mediáticamente la masacre ocurrida en Allende.

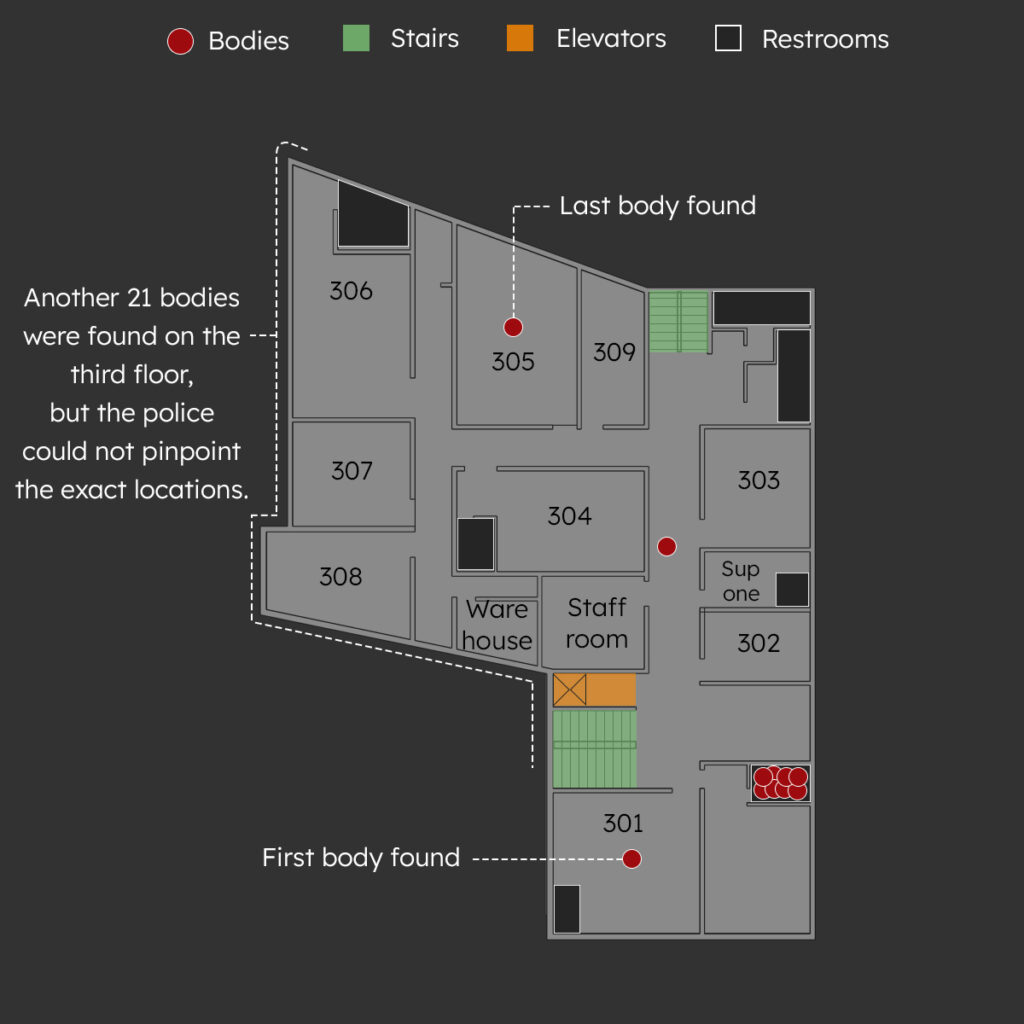

La ahora Fiscalía General de Justicia tiene registro de 28 personas desaparecidas en ese fin de semana y 42 entre enero del 2010 y agosto del 2012. La cifra se basa en las denuncias que recibió la dependencia.

Activistas y colectivos de búsqueda de desaparecidos estiman que pudieron ser cientos las víctimas de aquel fin de semana, pero es fecha que el número es impreciso.

MÁS DE UNA DÉCADA DESPUÉS

Luego de más 10 años la población sigue en alerta: cuando ven a un vehículo que no porta placas de Coahuila o de Texas sus rostros cambian, se alejan y los visitantes que curiosean por la ciudad son vigilados en todo momento por hombres desconocidos.

Aún se desconoce cuántas personas fueron víctimas de la matanza. La cifra oficial de la Fiscalía de Personas Desaparecidas de Coahuila es de 28, sin embargo, asociaciones civiles y colectivos de búsqueda de desaparecidos señalan que fueron más de 90 y que la masacre no se limitó a los tres días de violencia en Allende, sino que fueron meses de plagios y asesinatos en todo el norte del estado.

De esas propiedades, aseguran los lugareños, sacaron a familiares y personal de servicio: empleadas domésticas, vigilantes, choferes, jardineros y jornaleros. Resultado de esa cacería, decenas de personas desaparecieron y todavía no se sabe nada de ellas.

Después de una década, las fincas todavía lucen destruidas, llenas de basura. Éstas propiedades contrastan con las que están a su alrededor. Son inmensas en comparación con las viviendas de interés social y tienen detalles de casas estadounidenses, tendencia marcada por su cercanía con Eagle Pass, Texas.

Al ver llegar a los reporteros de El Sol de La Laguna, los vecinos se metieron a sus casas y cerraron puertas y ventanas. No saben nada o en esas fechas estuvieron “fuera de la ciudad”, es la respuesta de quienes quisieron responder a la prensa, que sólo pudo llegar a Allende con el apoyo de personal de seguridad del estado que los escoltó.

En la calle Nogalar, donde había una quinta de descanso del “soplón”, los perros de las casas de enfrente empezaron a aullar y los móviles de viento, usados comúnmente como amuleto para ahuyentar las malas vibras, comenzaron a sonar.

El miedo de los pobladores es justificado, pues es reflejo de los desaparecidos que se han registrado en los últimos meses en la región. Sigue siendo una zona de riesgo.

Las familias de los desaparecidos tienen todavía la esperanza de saber qué fue lo que les pasó, porque viven con dolor y no han logrado cerrar el ciclo. Aun así, tienen miedo de hablar.

LAS CICATRICES

Además de las fincas destruidas, que persisten como cicatrices de una herida grave, en la ciudad hay dos memoriales. Uno en la plaza principal, construido el 27 de junio de 2019. Tiene cuatro columnas, donde versa una palabra en cada una de las columnas: Verdad, justicia, reconciliación y no repetición.

A su costado izquierdo, viéndolo de frente, tiene una placa que dice: “Por las violaciones graves a los Derechos Humanos posteriores en los municipios de Allende, Piedras Negras y la Región Norte del Estado de Coahuila, así como por las detenciones arbitrarias y desapariciones forzadas cometidas con posterioridad. El Gobierno del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza reafirma el compromiso a las víctimas de desaparición de un ser querido, para garantizar sus derechos de justicia, verdad, reparación de daño y no repetición”.

El otro es un obelisco situado a la salida de Allende, a menos de un kilómetro de llegar a Morelos. Se edificó en octubre de 2015; fue gestionado por la asociación civil “Alas de Esperanza” y construido por el Gobierno del estado y la autoridad municipal de ese tiempo.

Tiene una llama hecha de latón y una placa que reza: “En memoria de nuestros seres queridos. Pueden pasar los días y podrá separarnos la distancia pero siempre nos unirá ‘El amor y la Esperanza’. Todos unidos por la paz ‘Alas de Esperanza’”.